Eling One Place Study

A Study of the Parish of Eling in the County of Hampshire, or sometime known as the County of Southamptonshire.

I refer you to the Millbrook One Place Study in the first instance. That has a lot of the background information which would be repetitive if just repeated here.

Progress;

- Initial StoryMap added to Overview 1/12/2024.

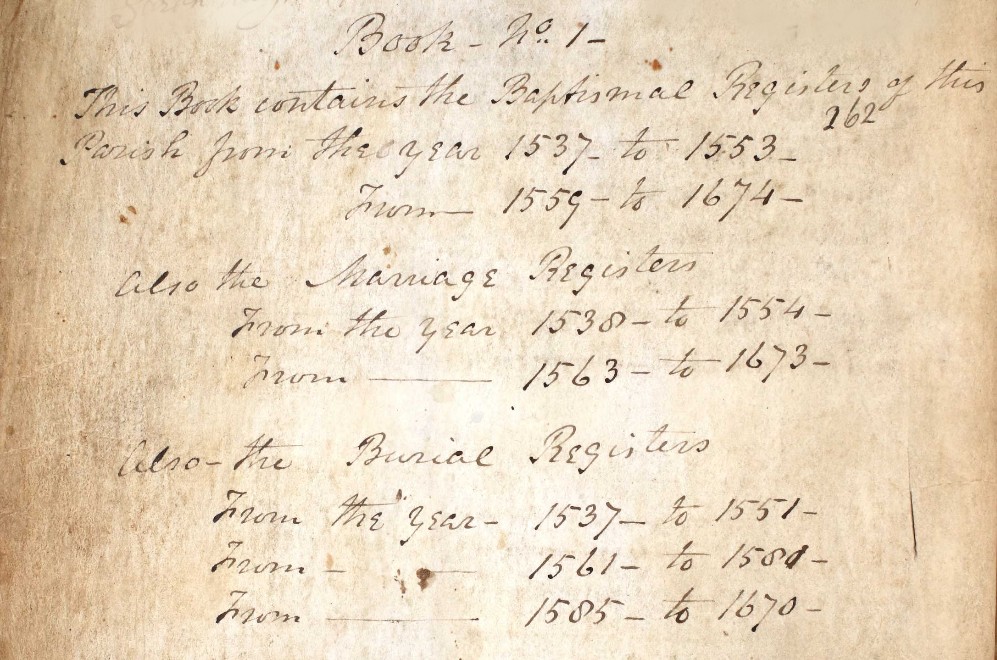

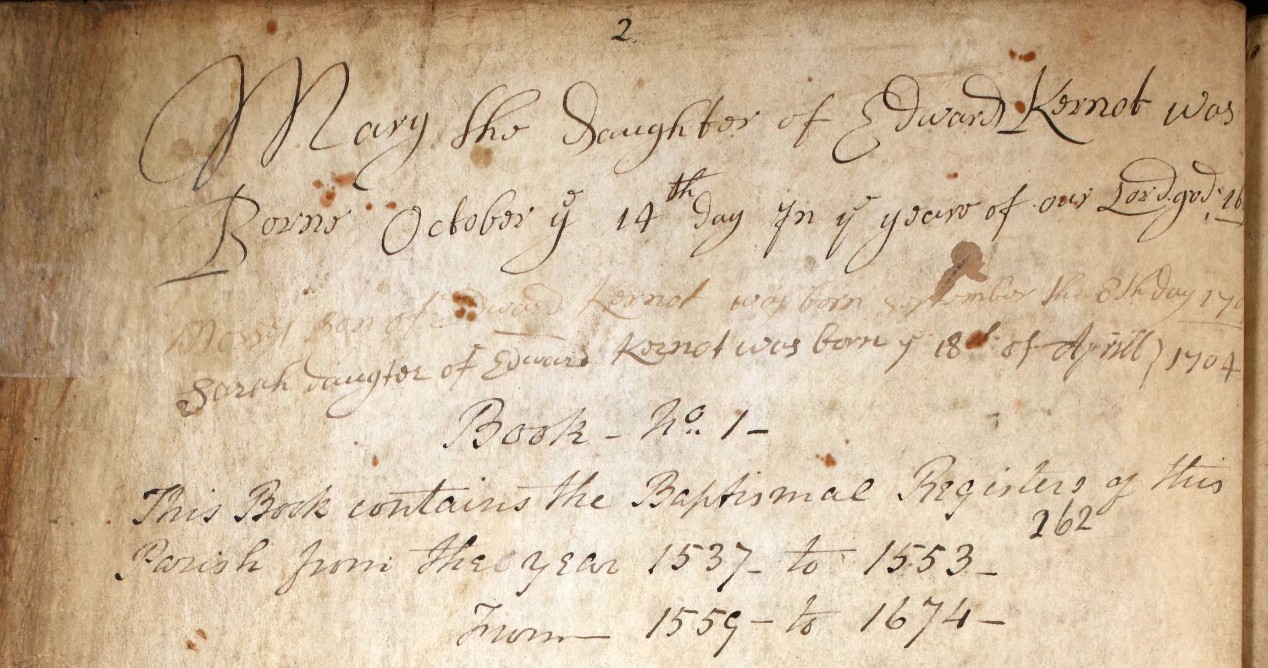

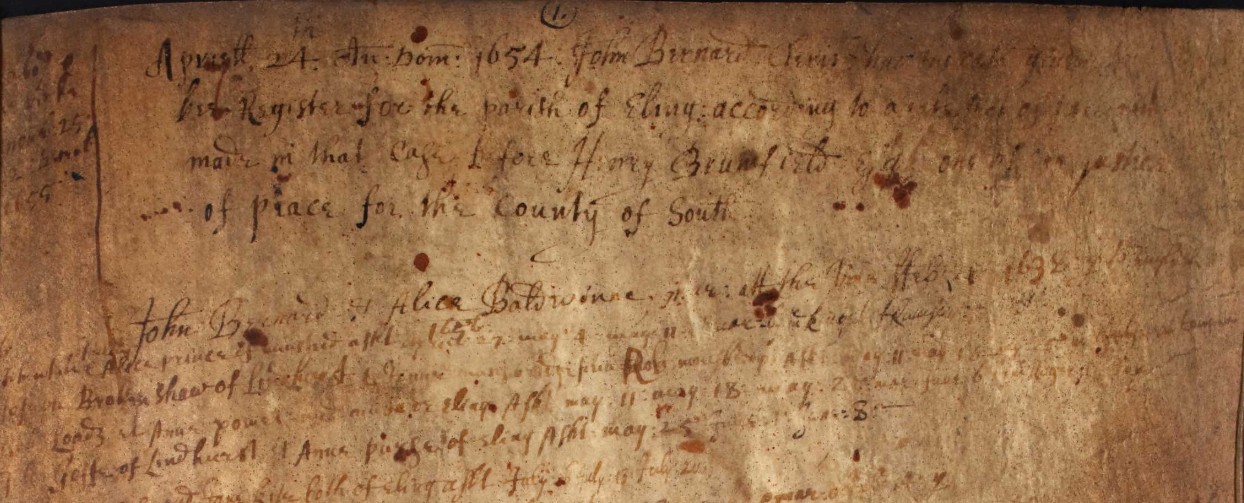

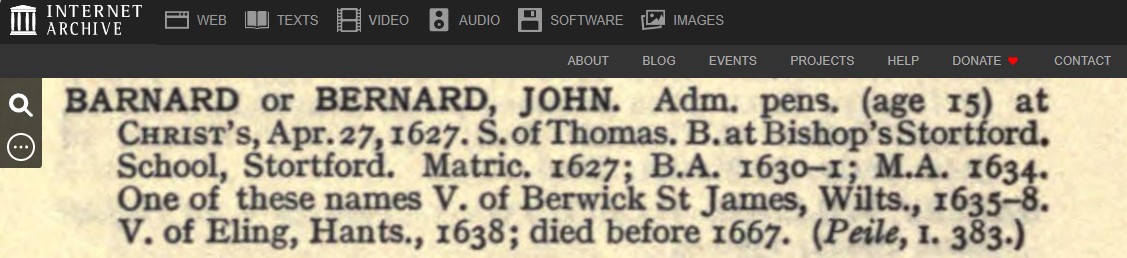

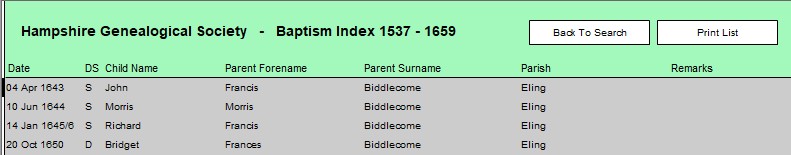

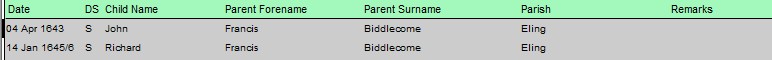

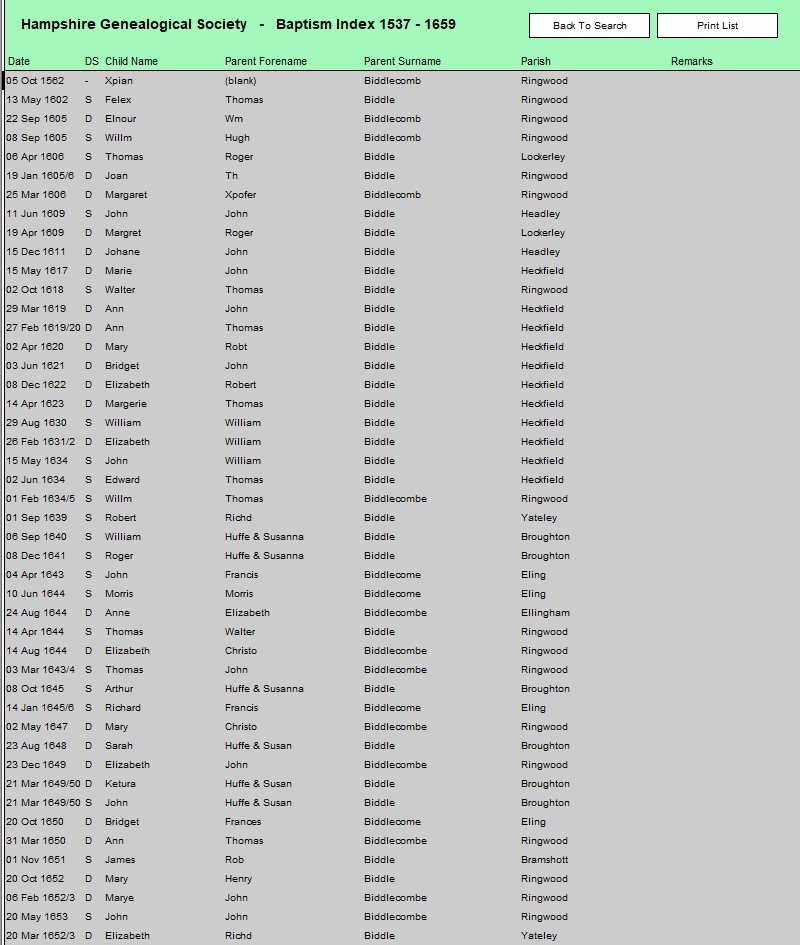

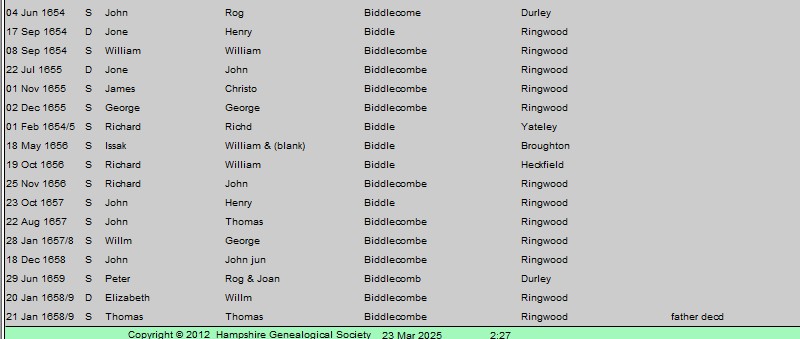

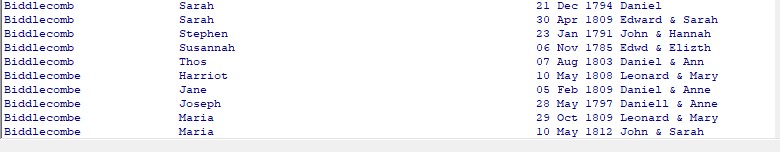

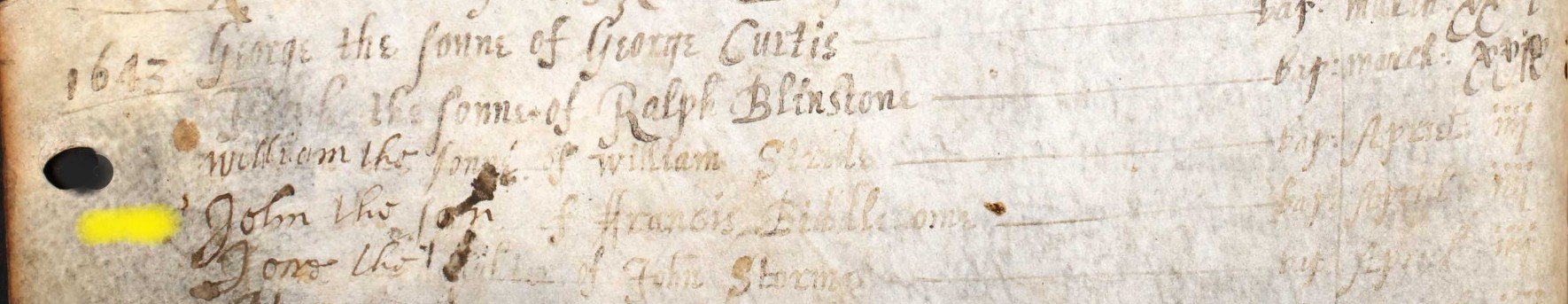

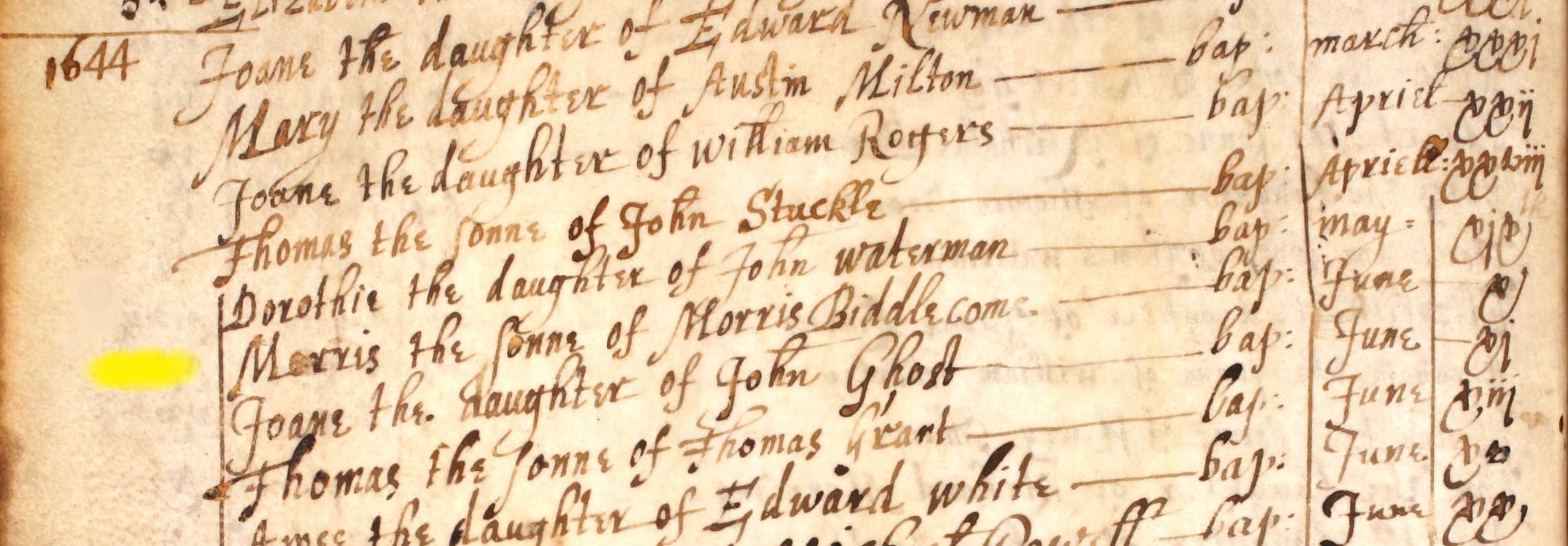

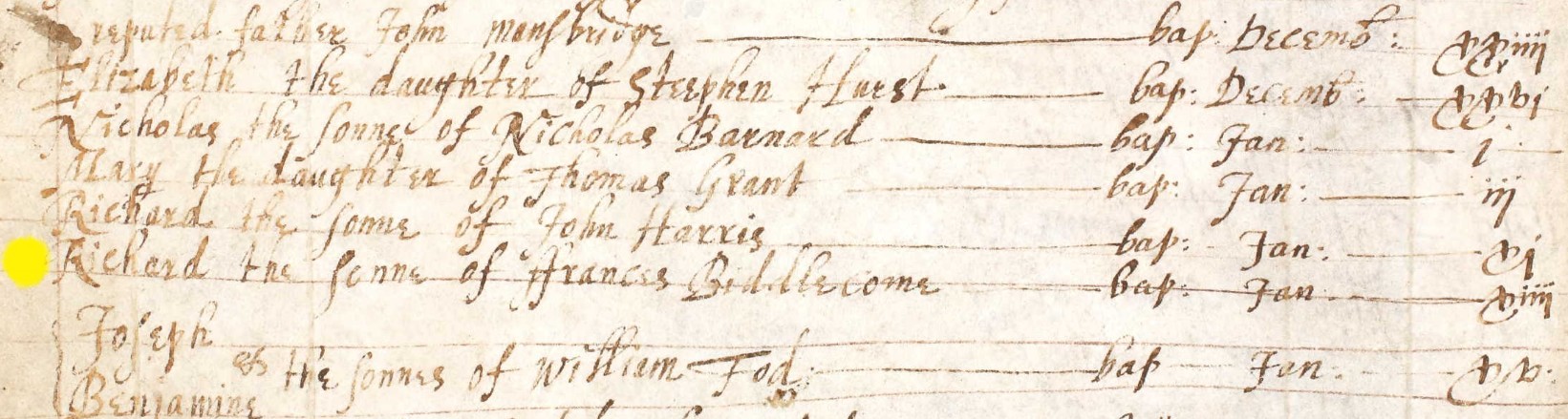

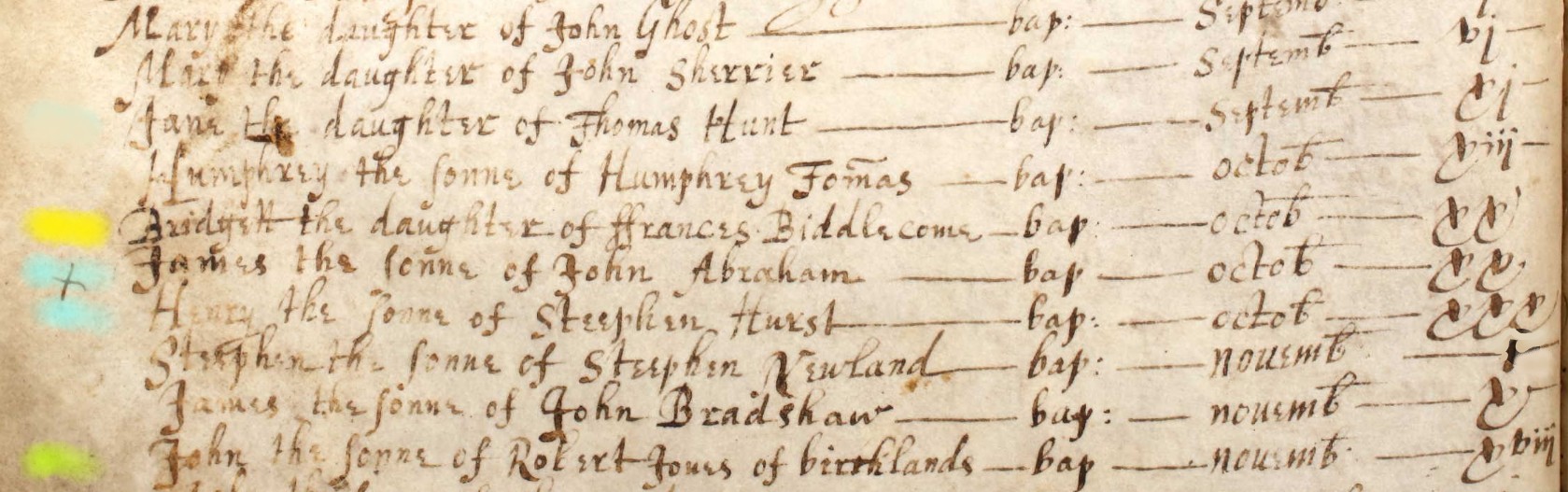

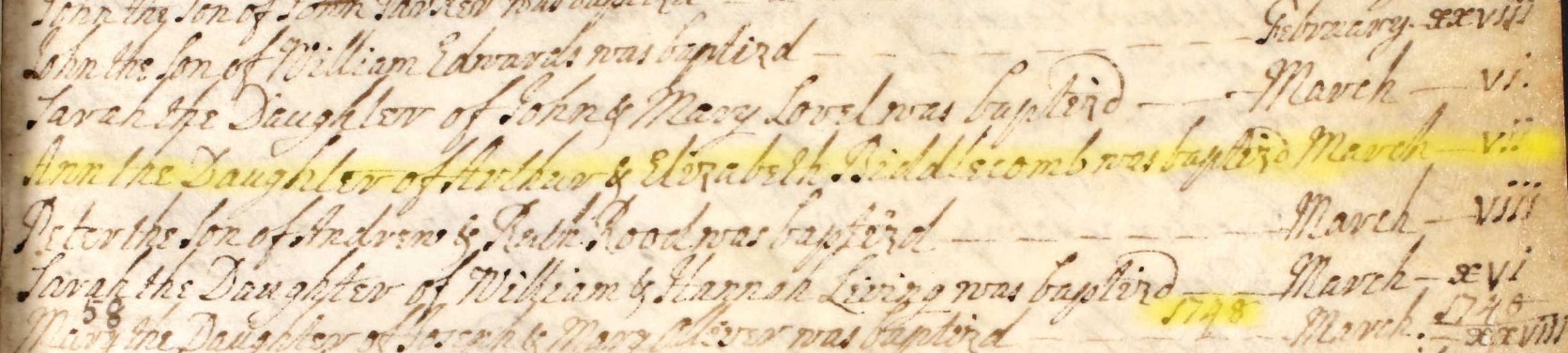

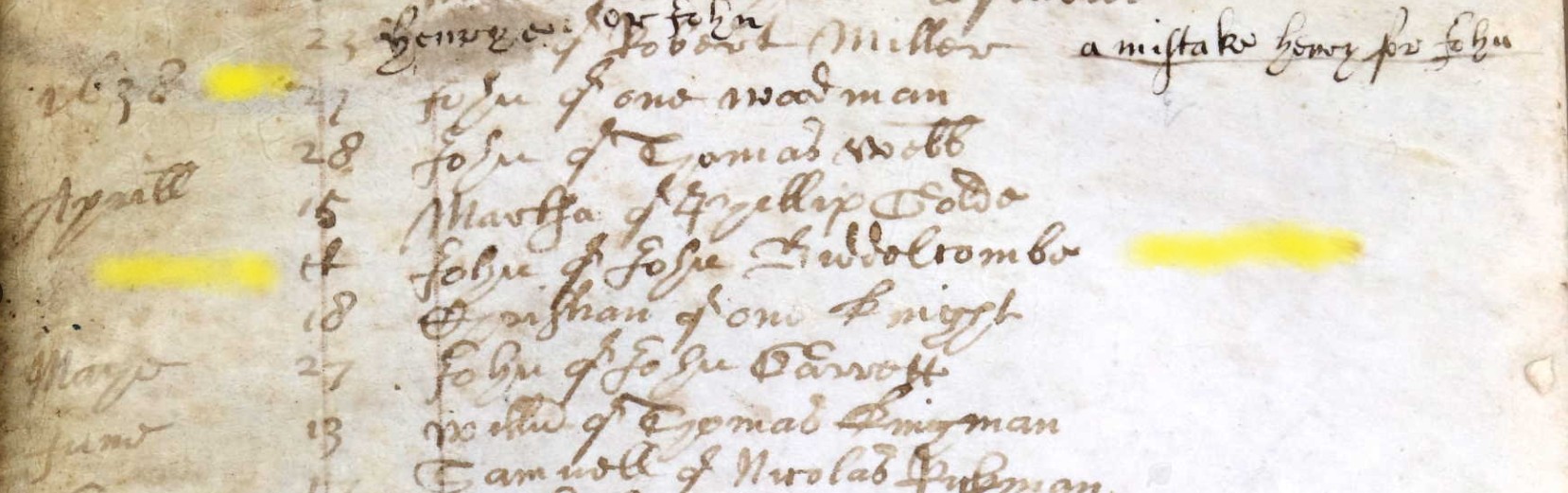

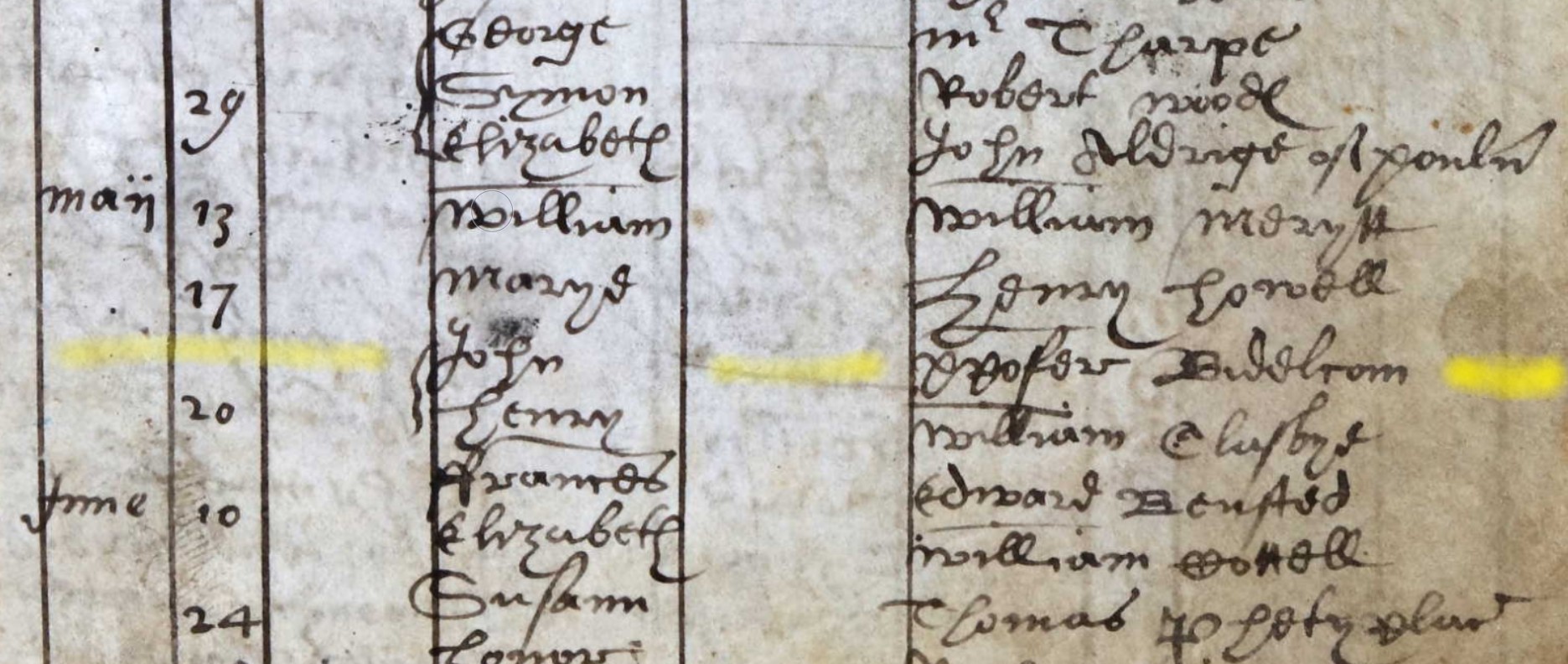

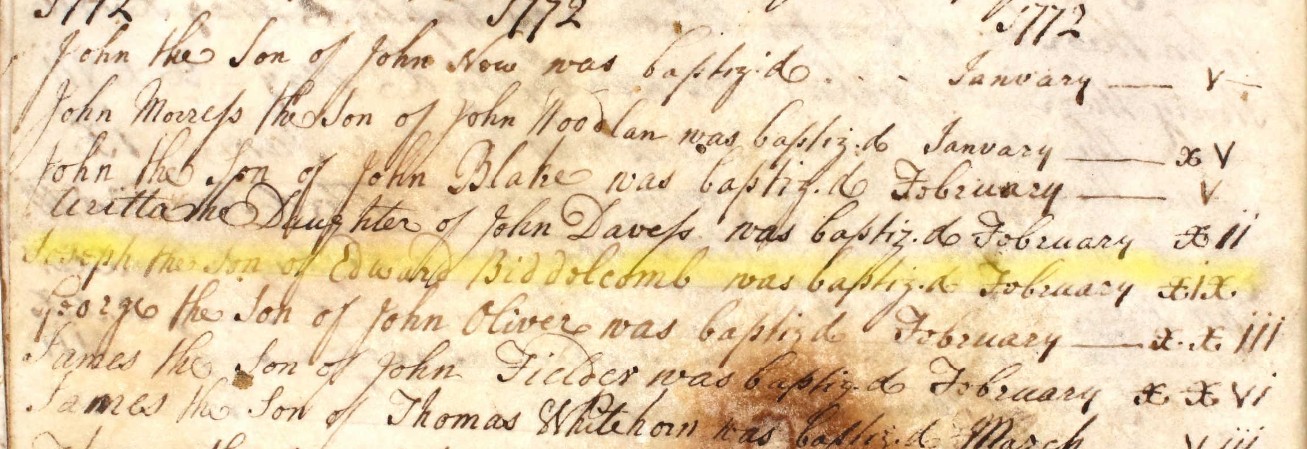

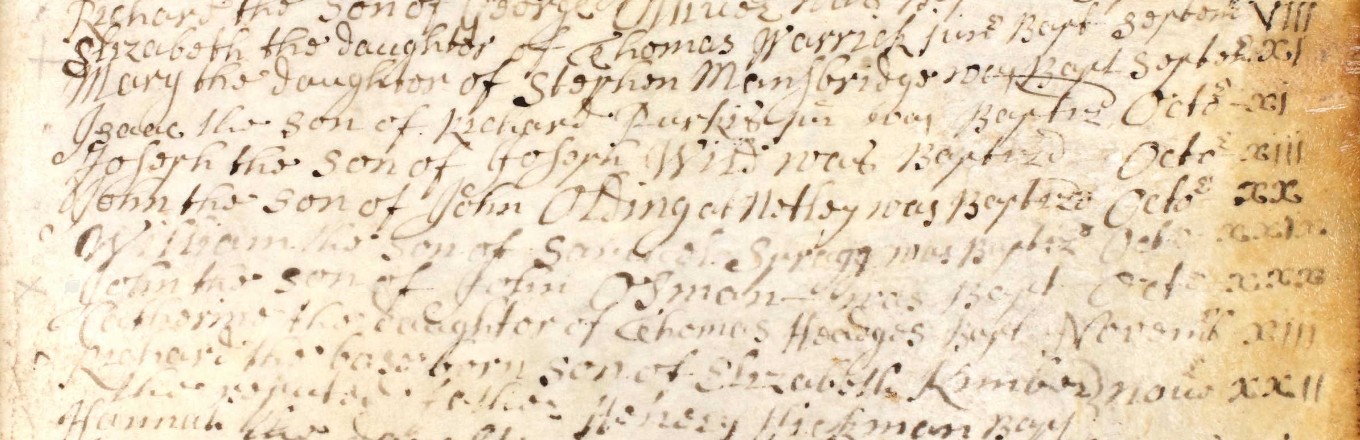

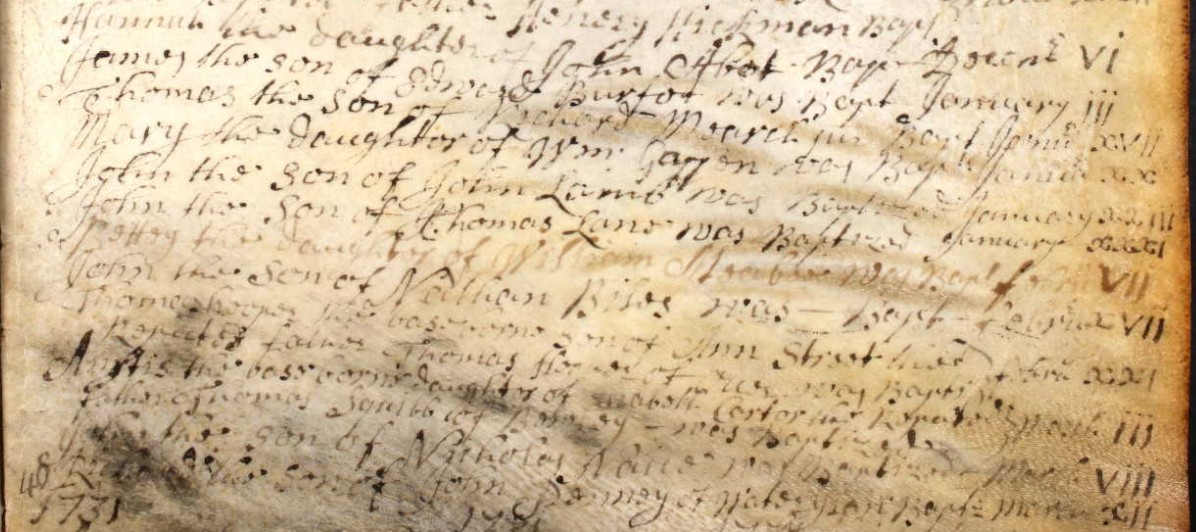

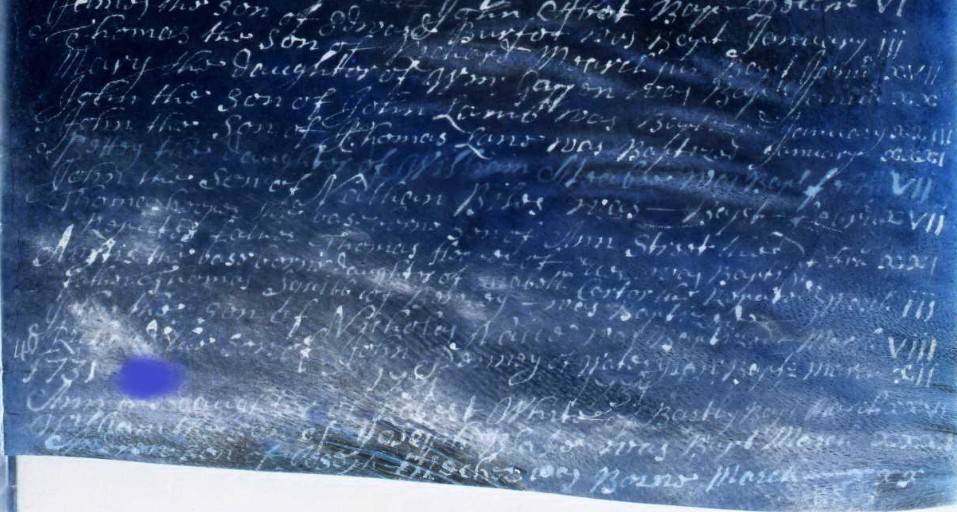

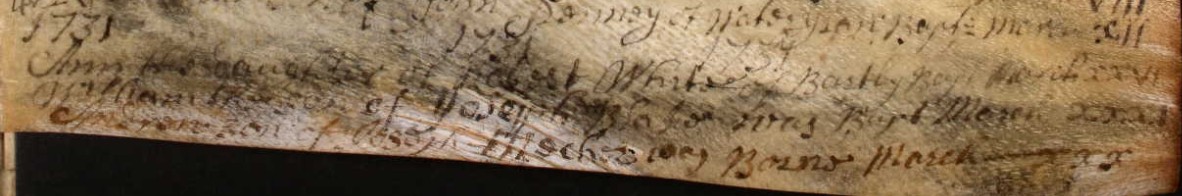

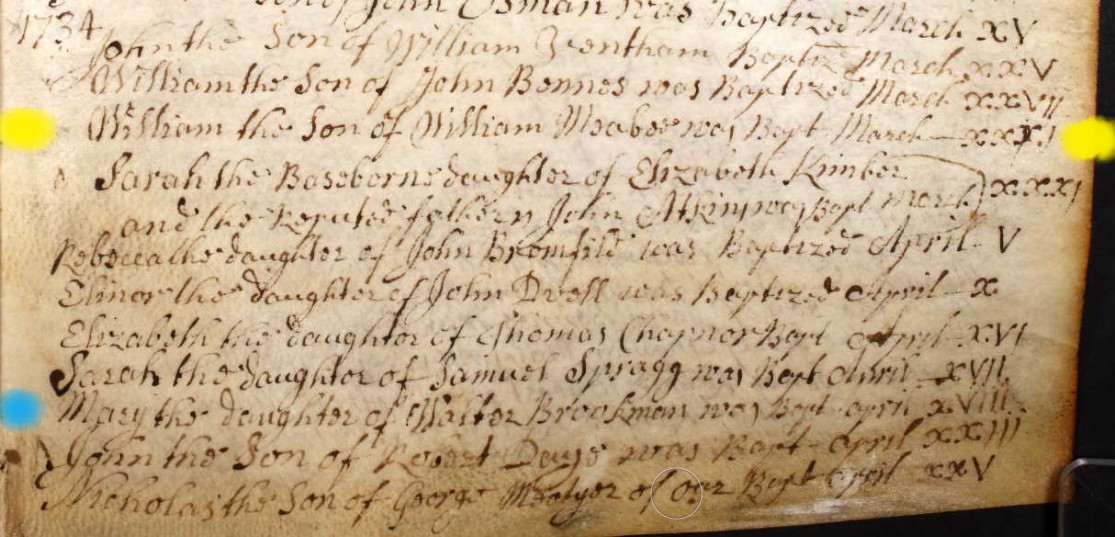

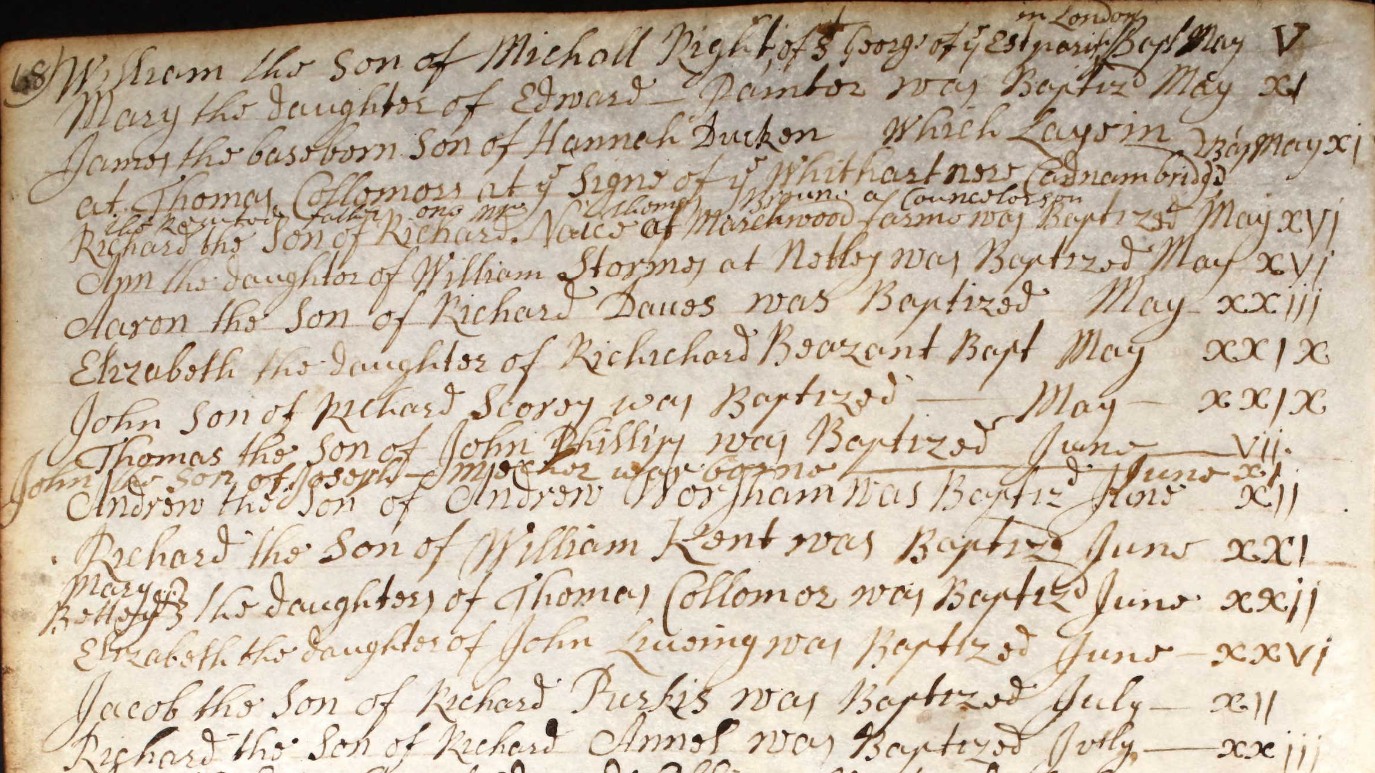

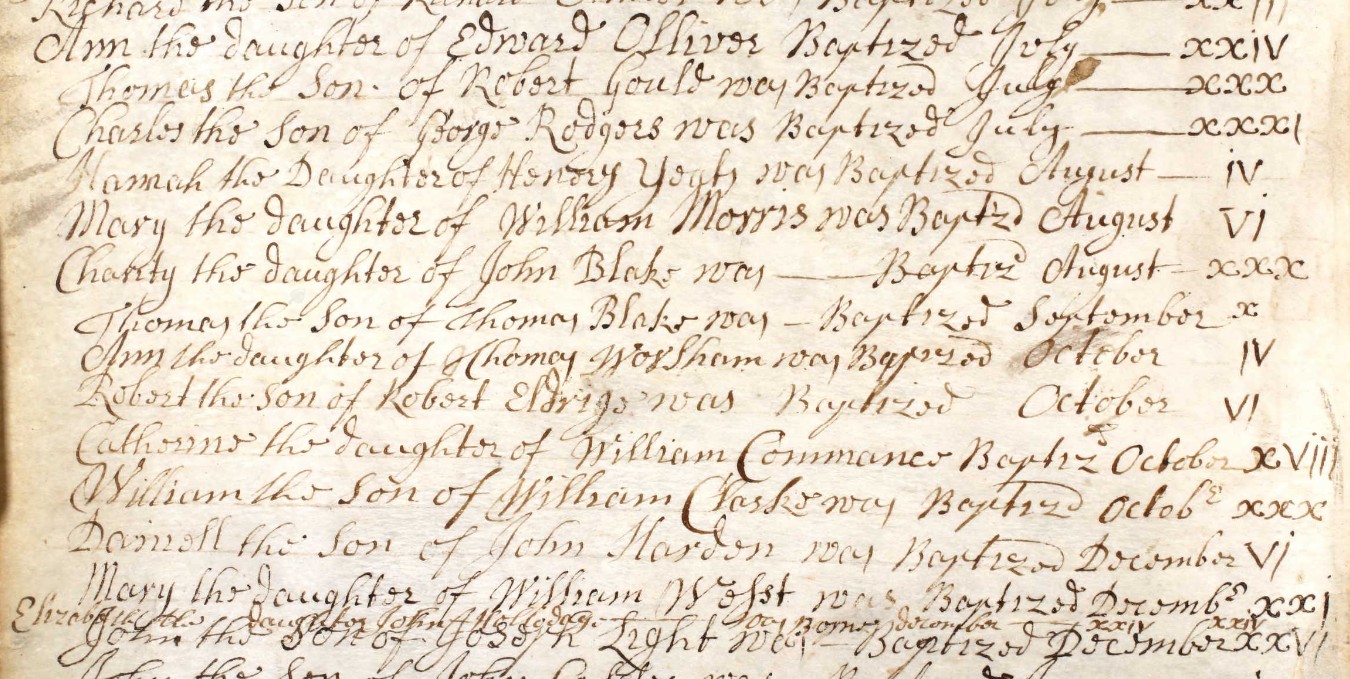

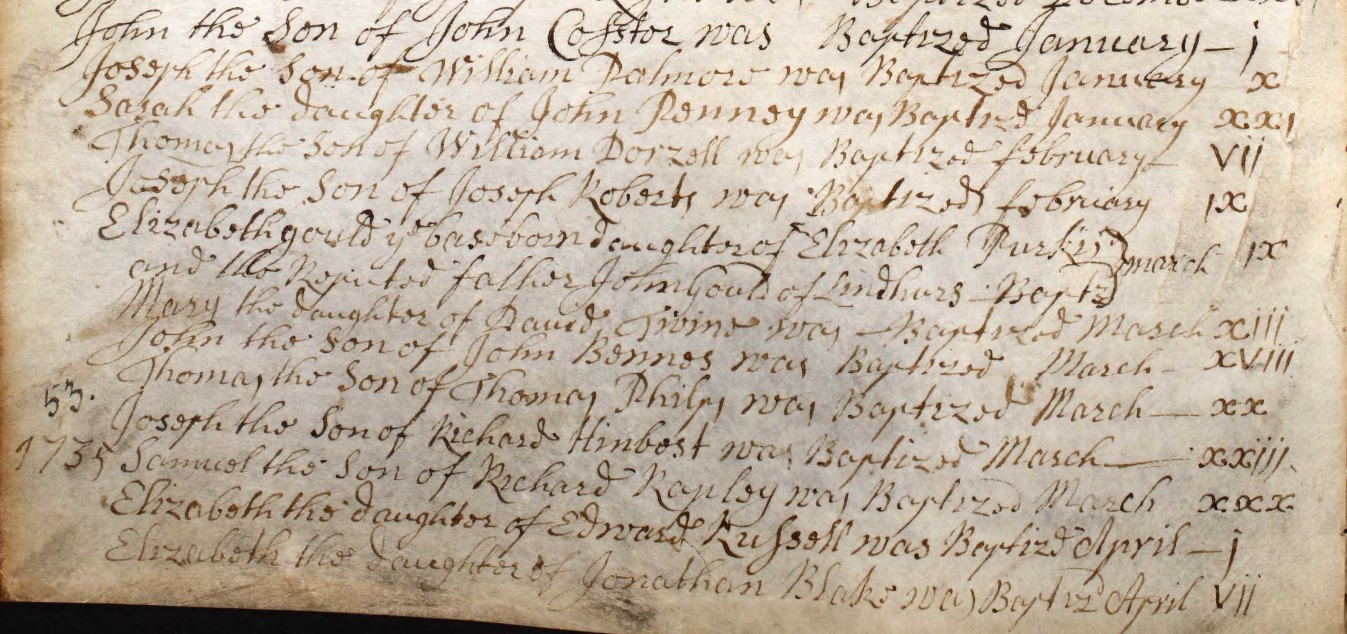

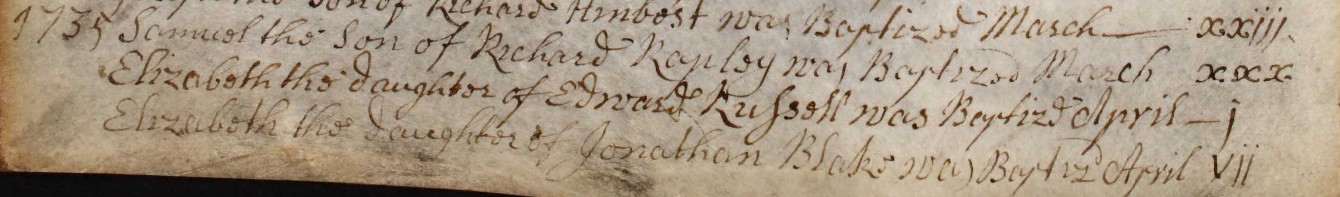

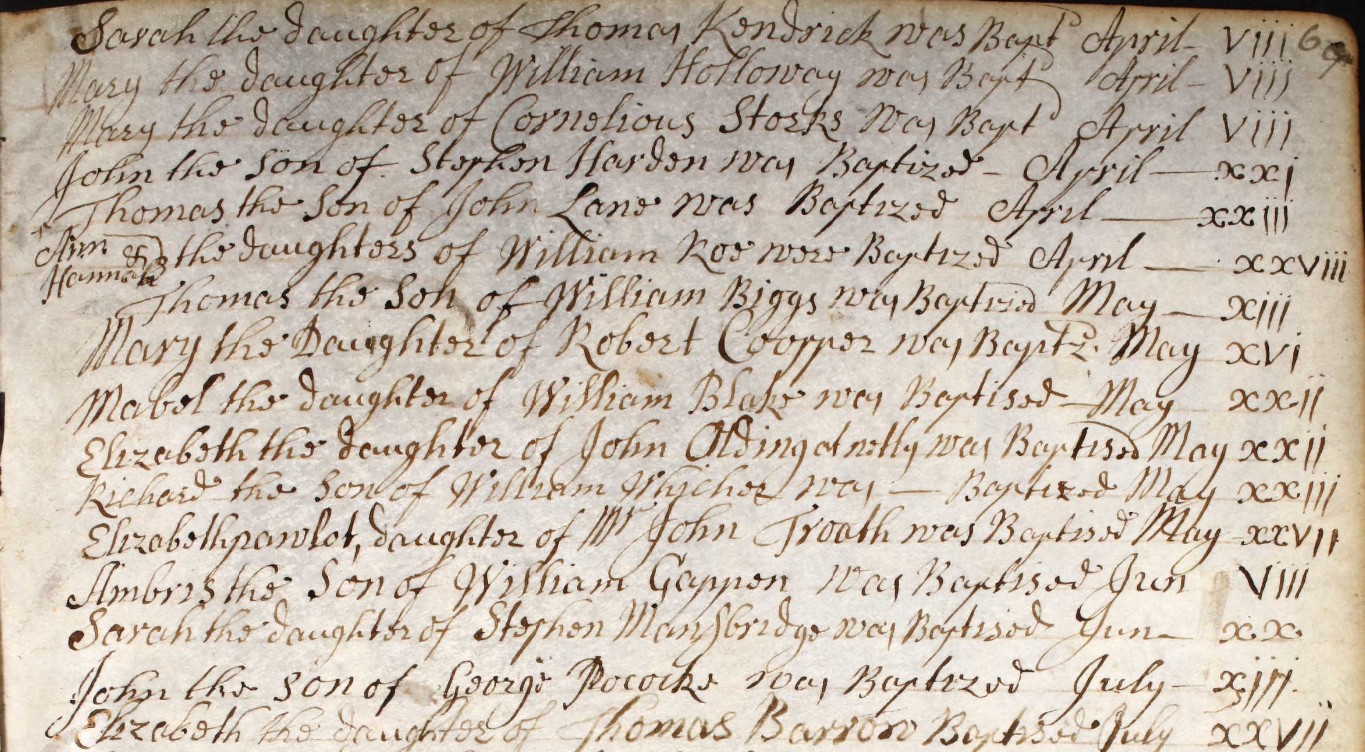

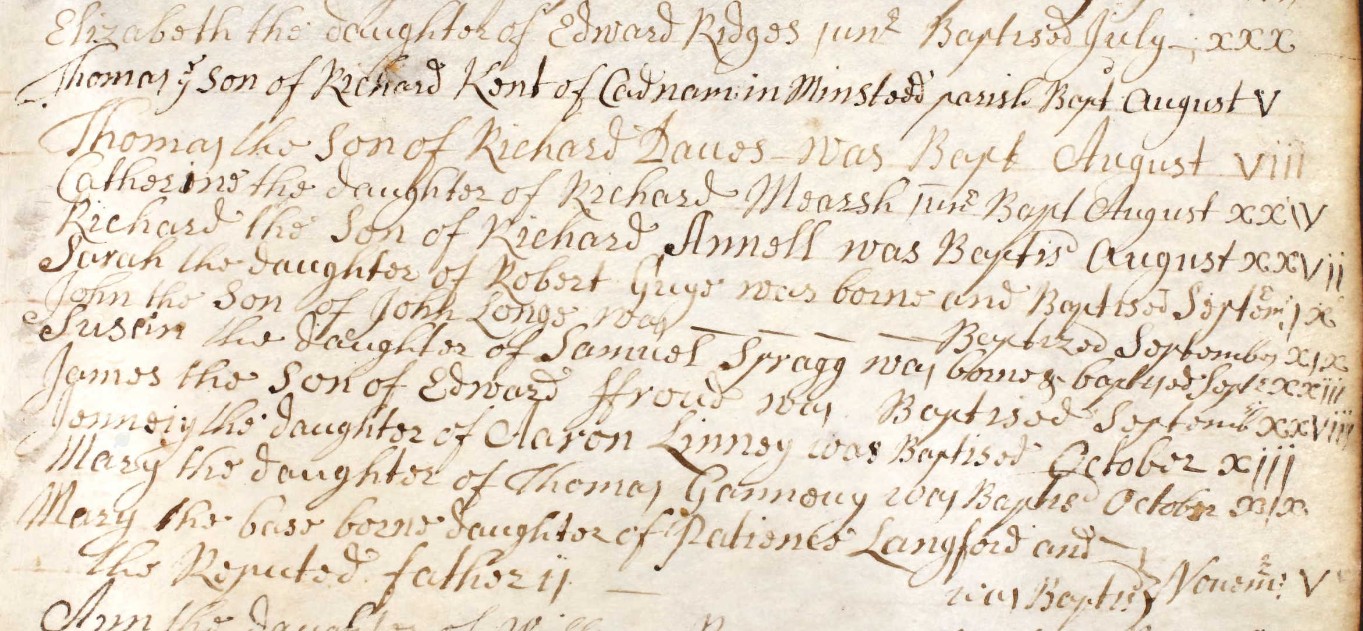

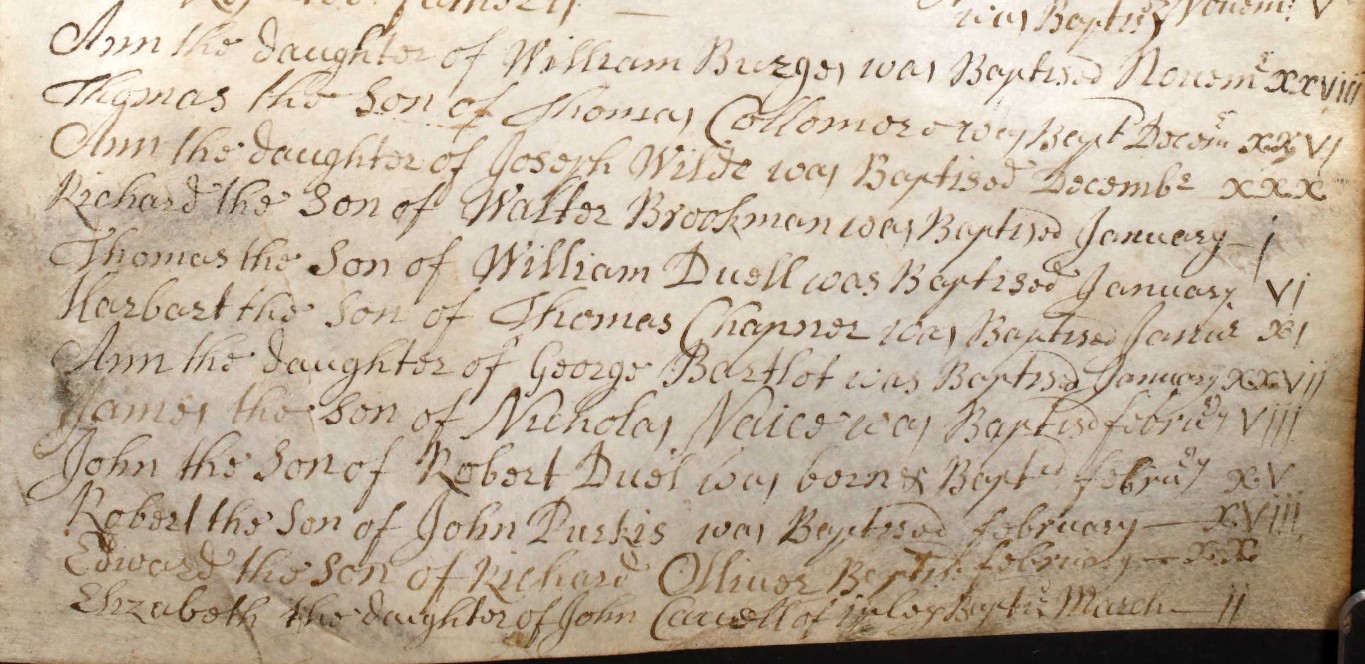

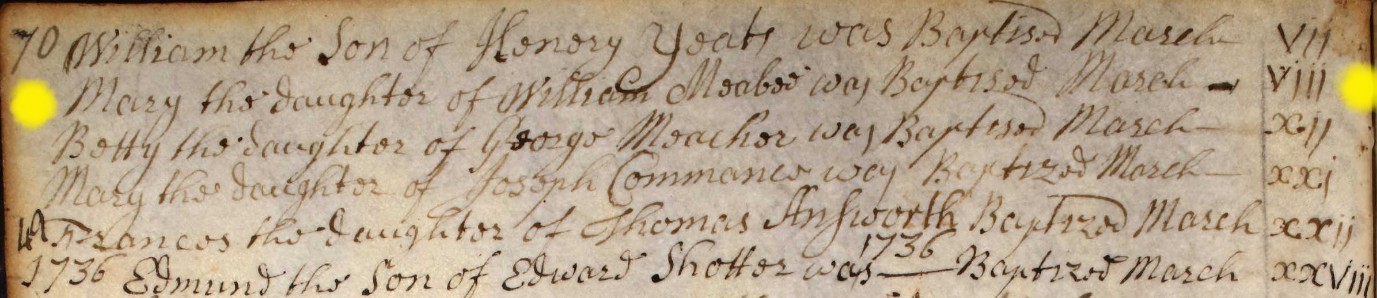

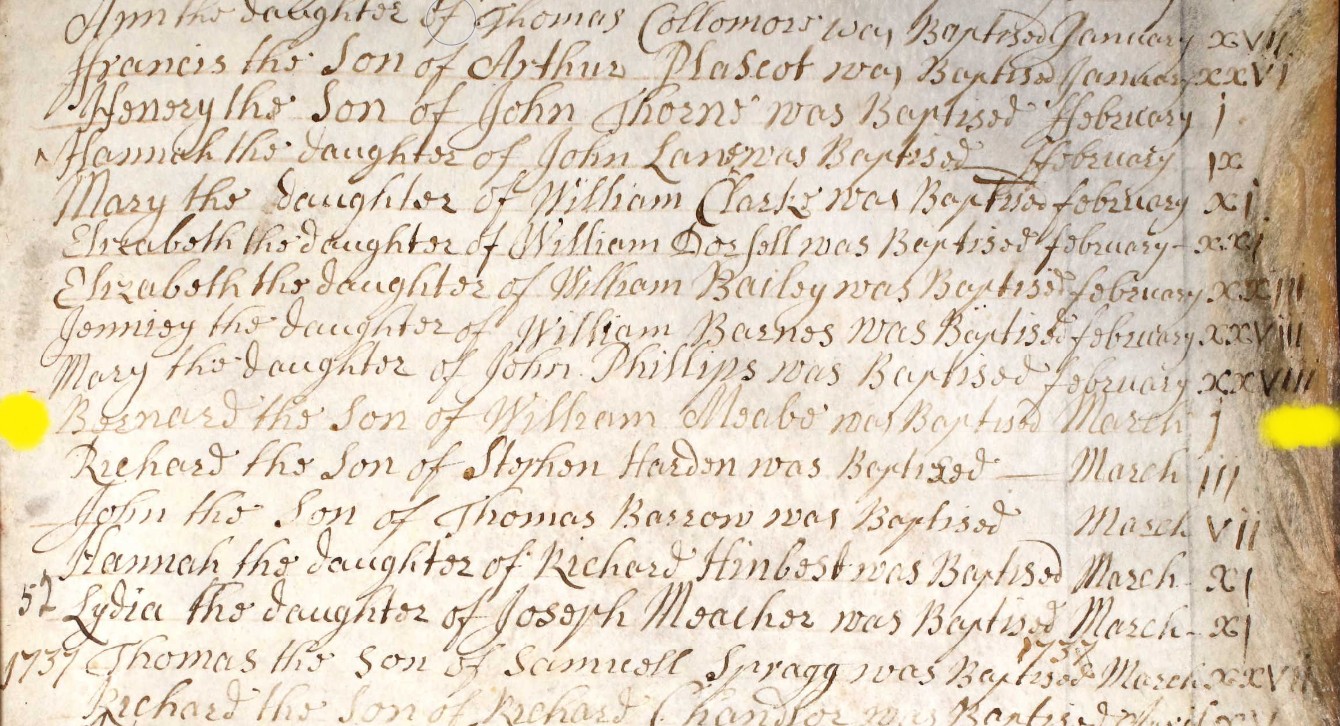

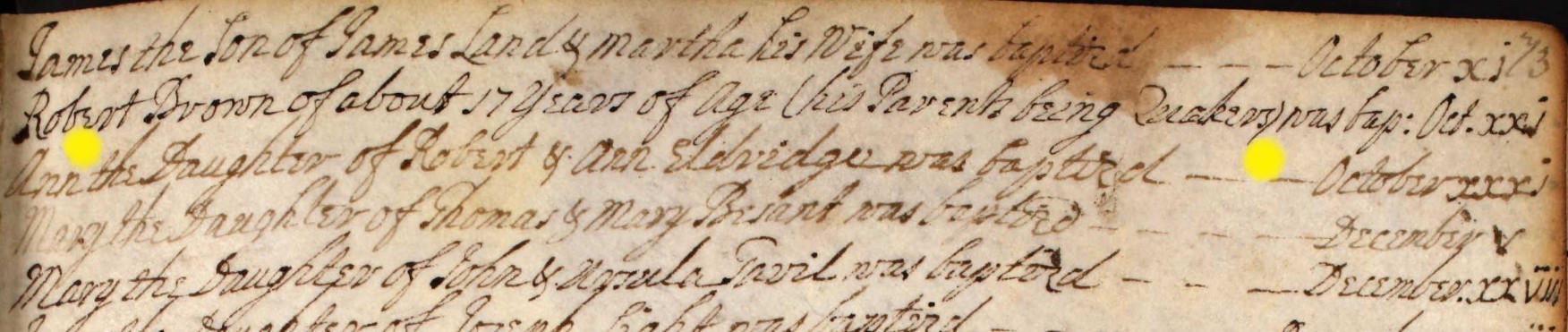

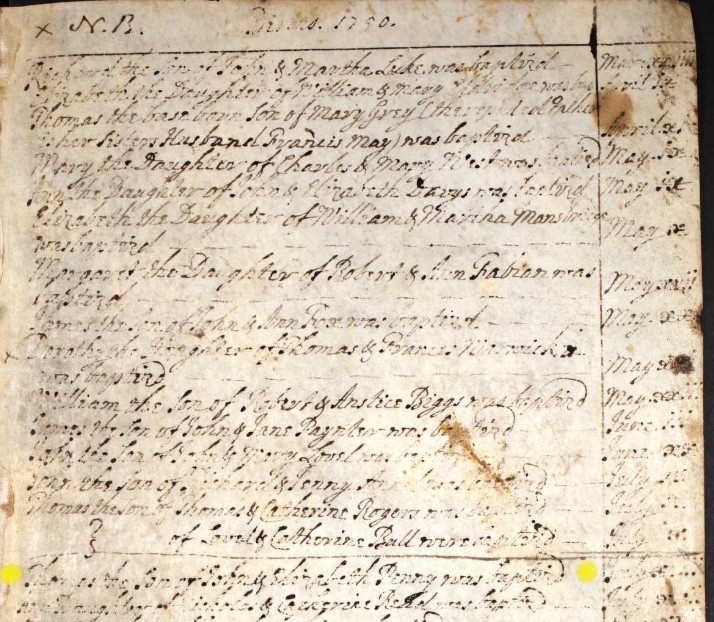

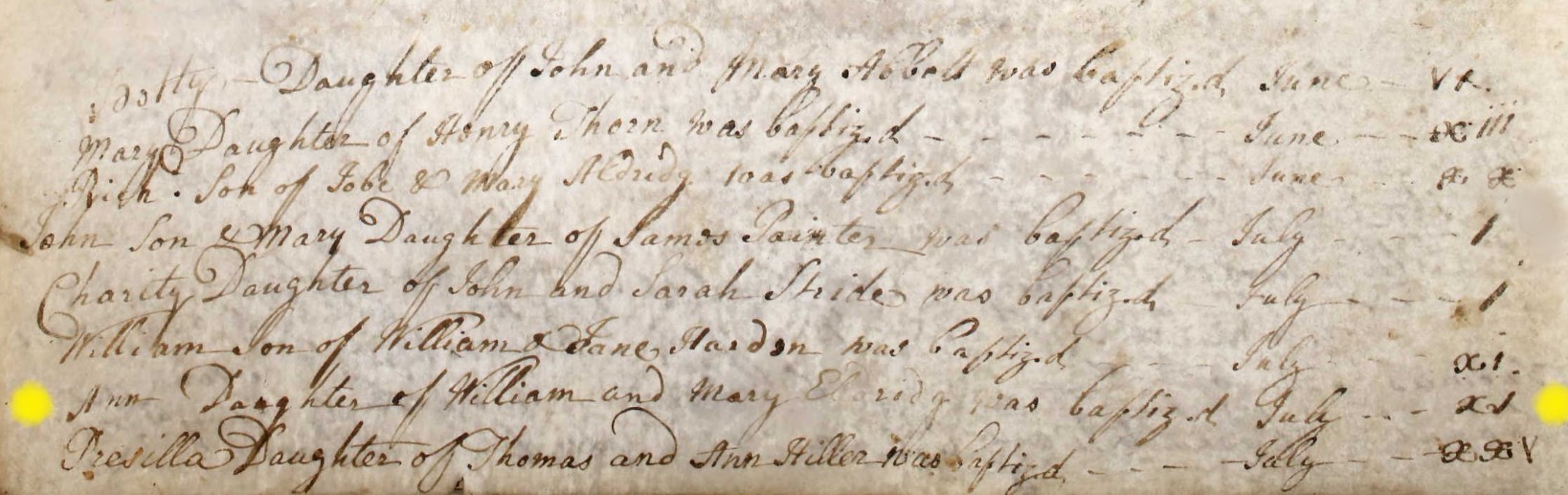

- Parish Records, Baptisms, new spreadsheet template, commenced Sept 2025, with the Register book 1537-1674.

- Researching before 1066 and Prehistory Oct 2025.

- 'The Place' added, and the Article Eling Hampshire incorporated Nov 2025.

- 'How I make use of Tithe Apportionment and Maps' separated from 'Tithe Commutation Act 1836' and incorporated as article in article to provide consistent information. Nov 2025.

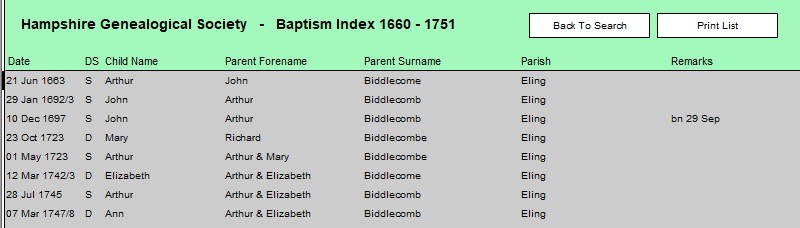

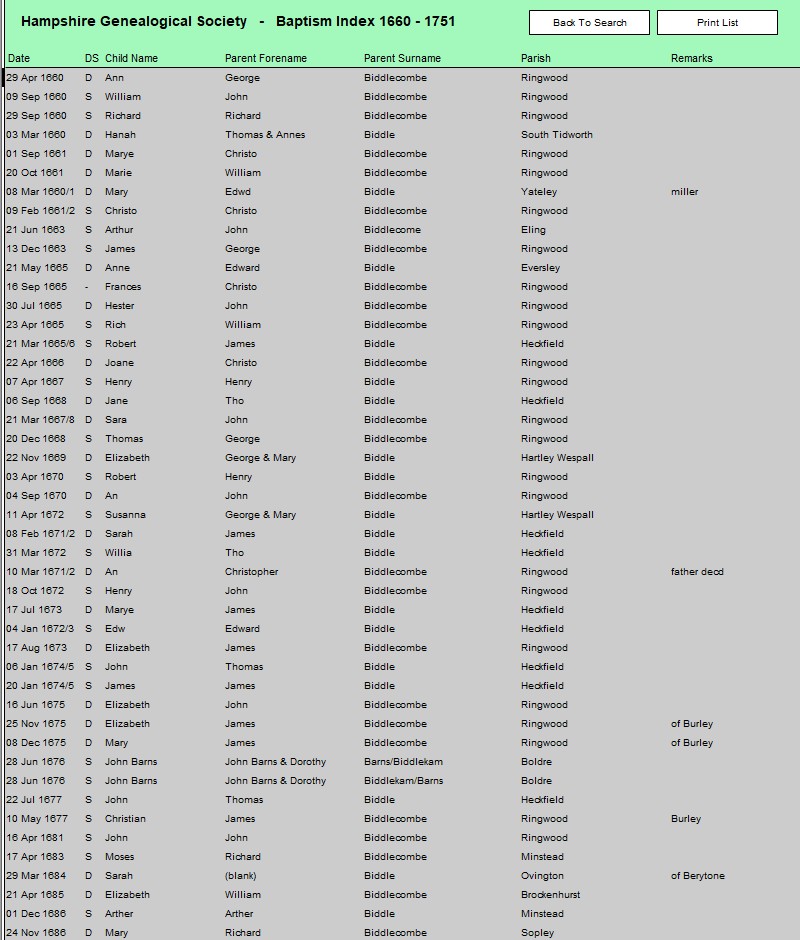

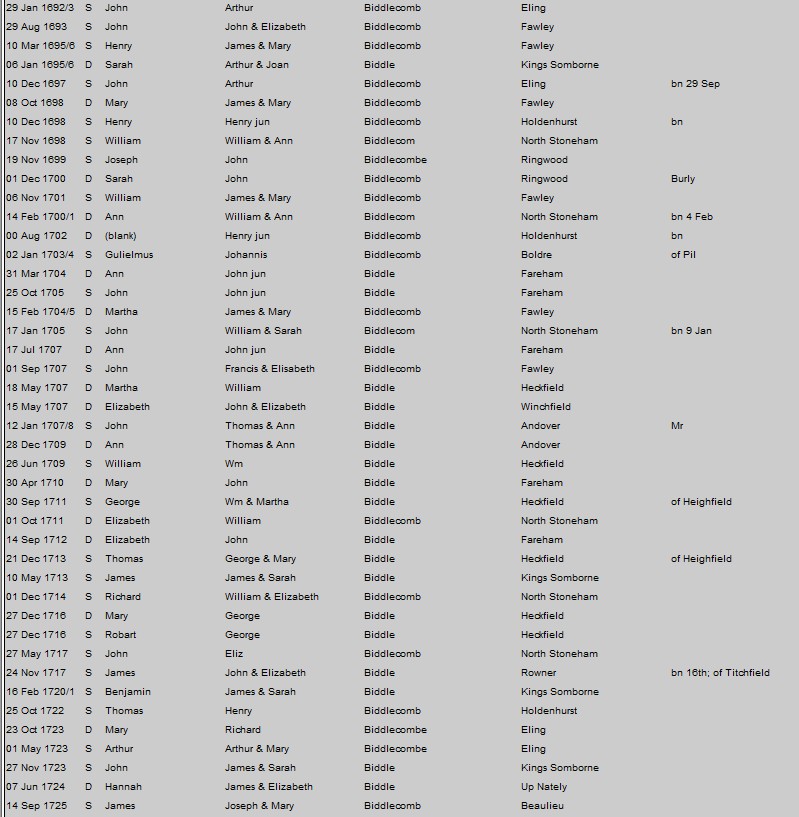

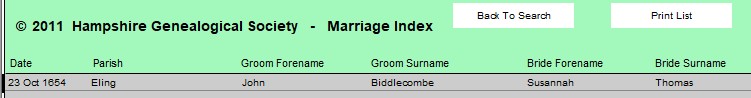

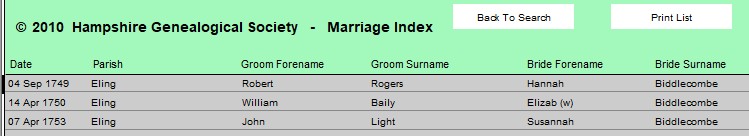

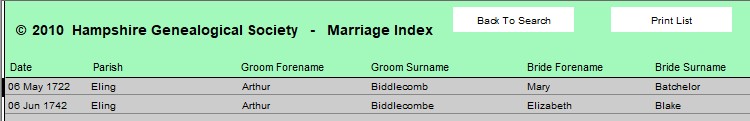

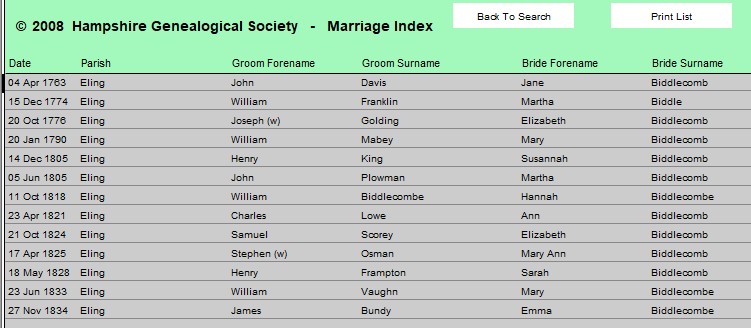

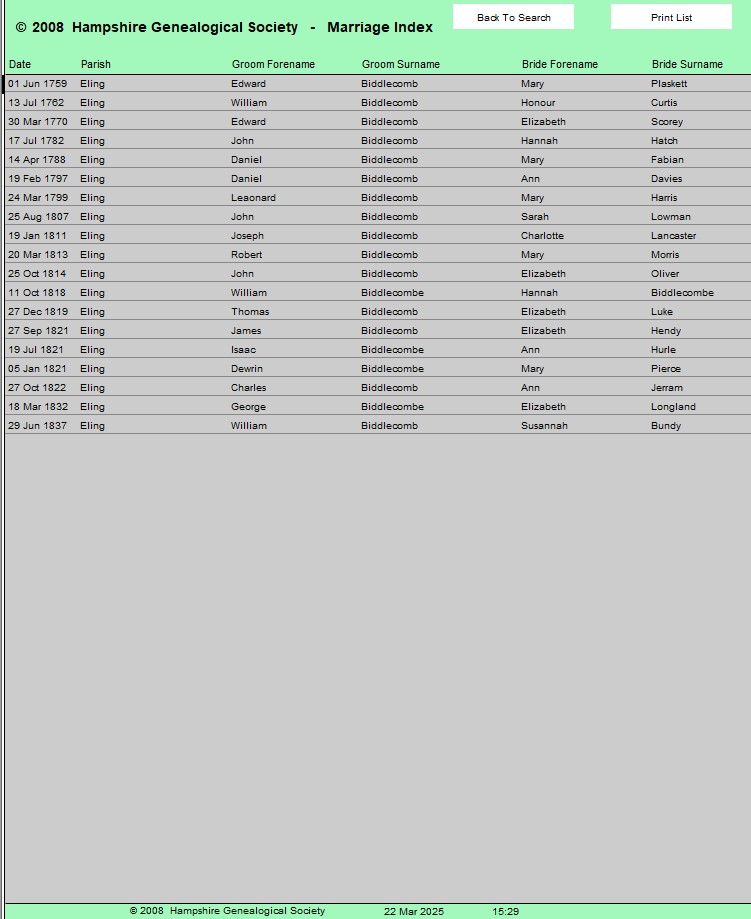

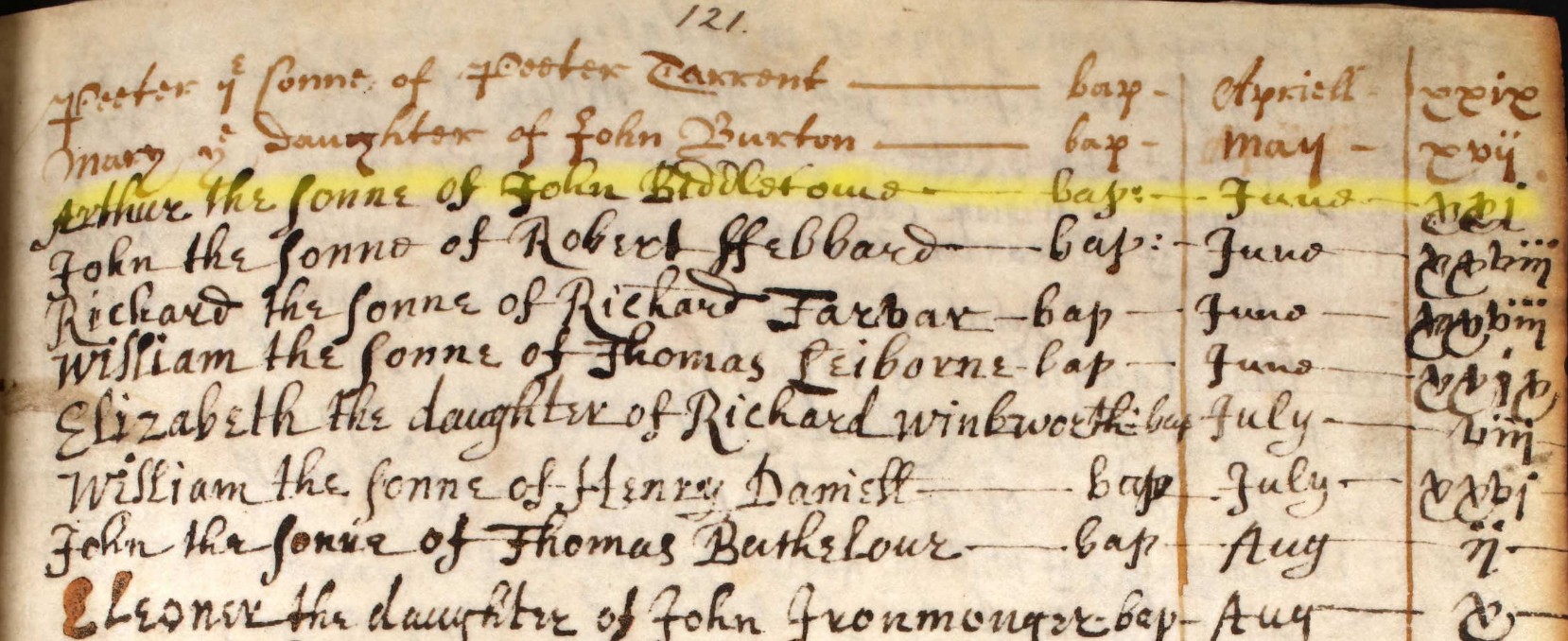

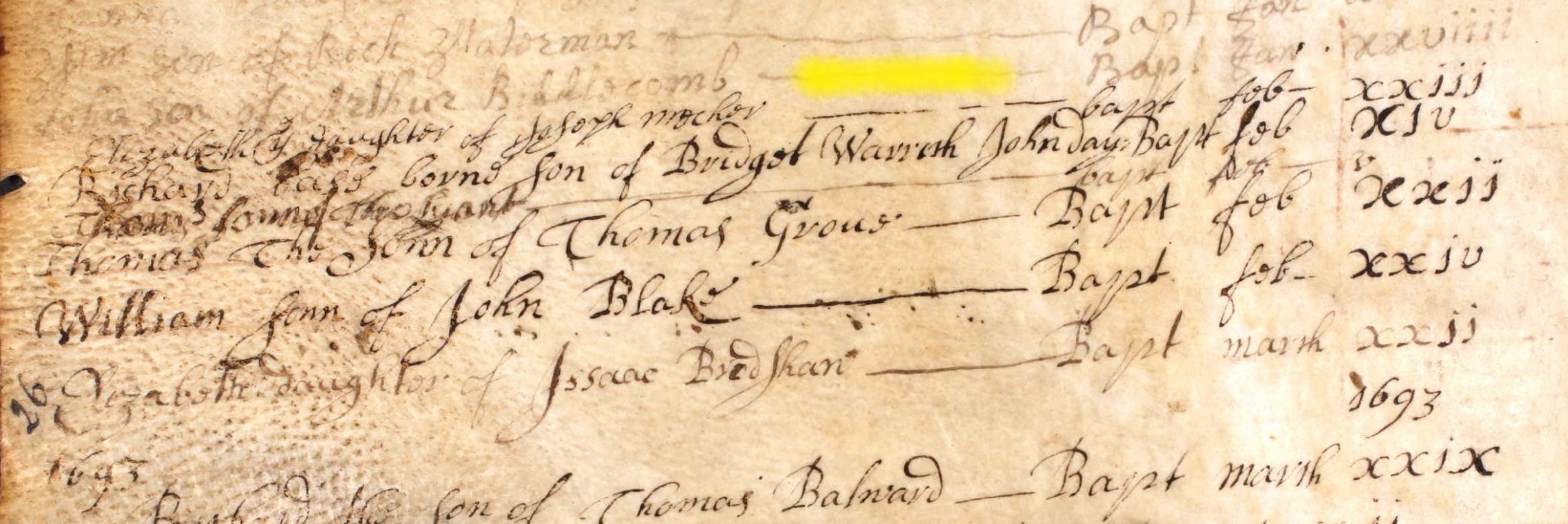

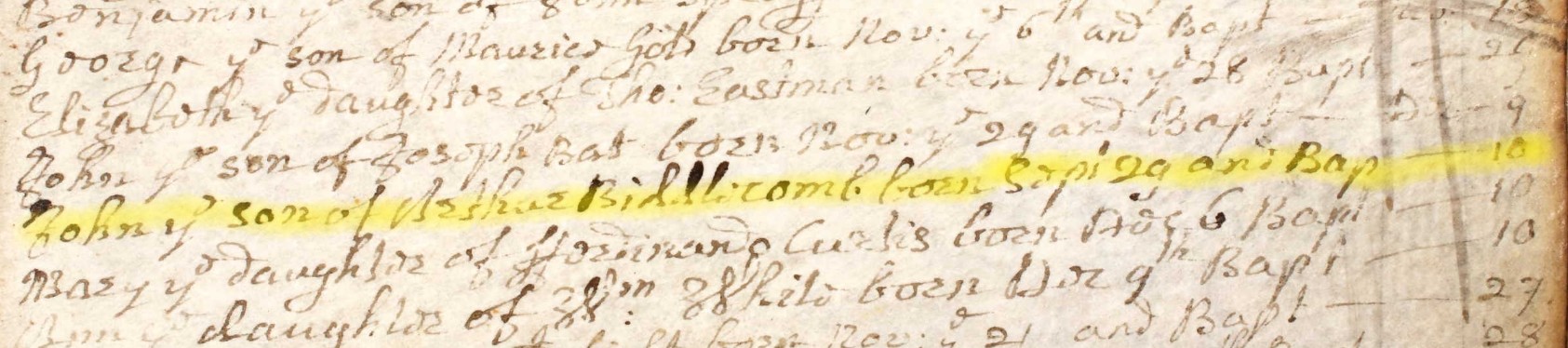

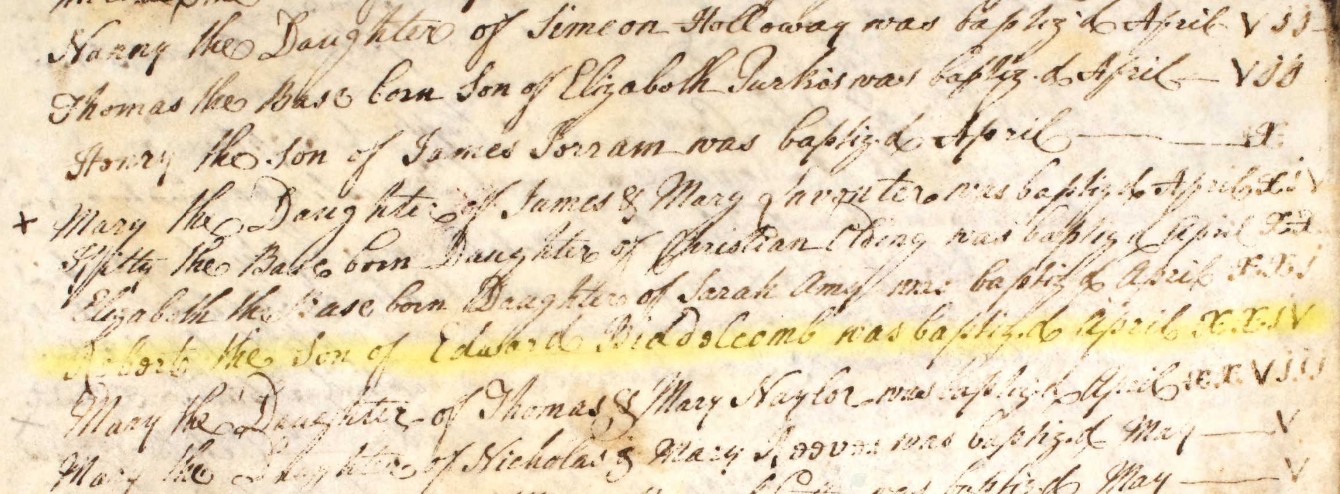

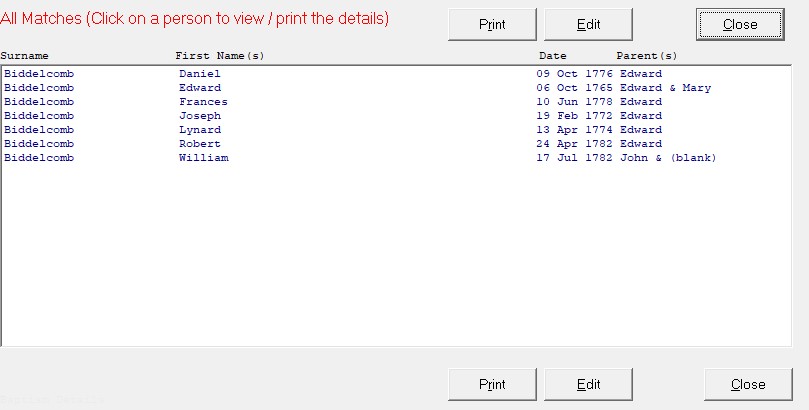

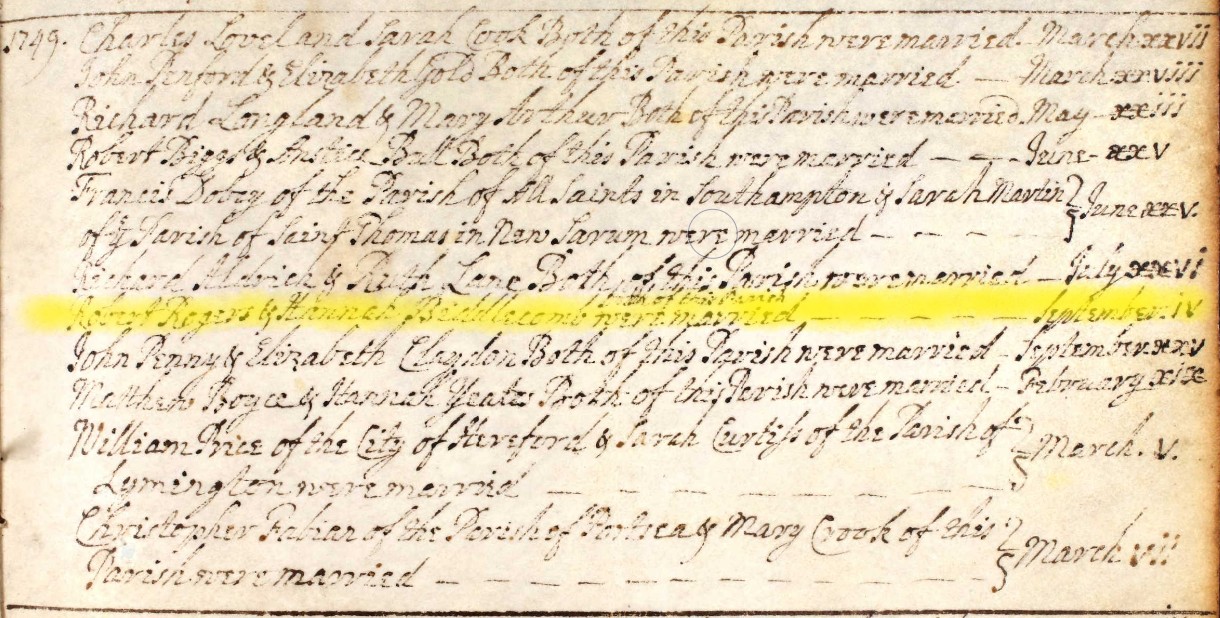

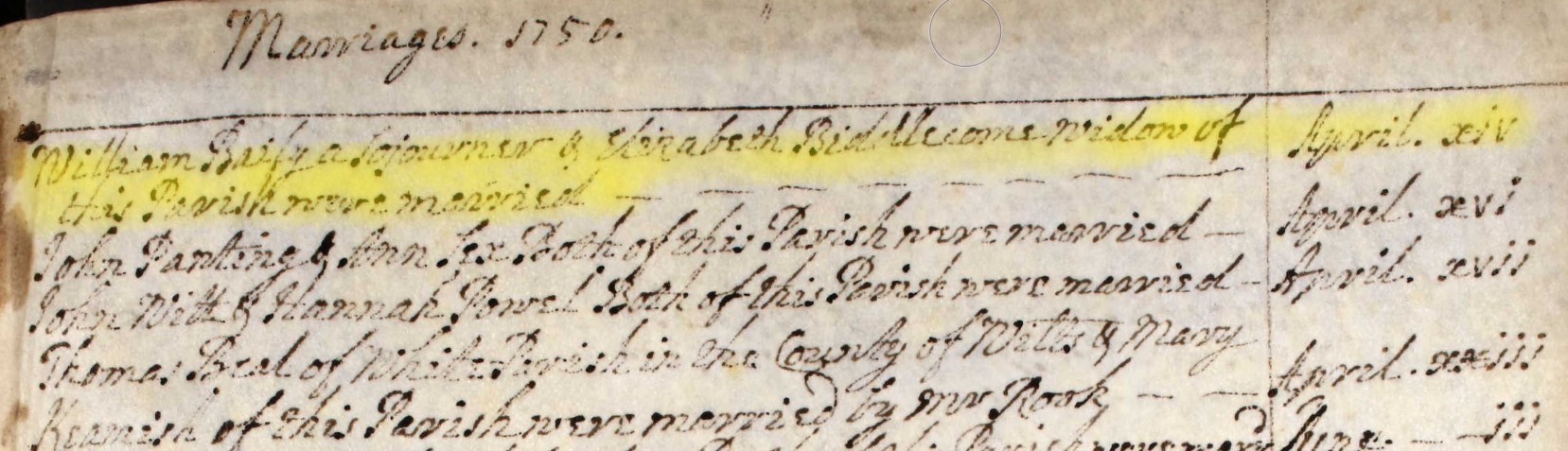

- Added a section for 'Related Articles' and inserted 'Biddlecombe families of Eling' Nov 2025.

Overview

Overview

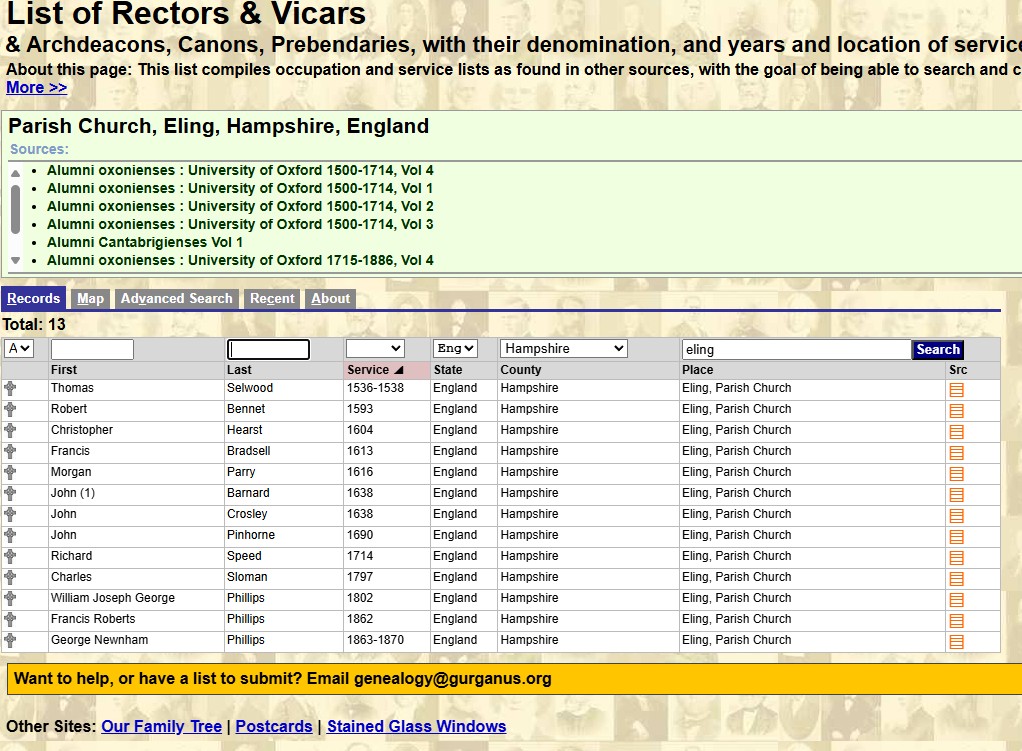

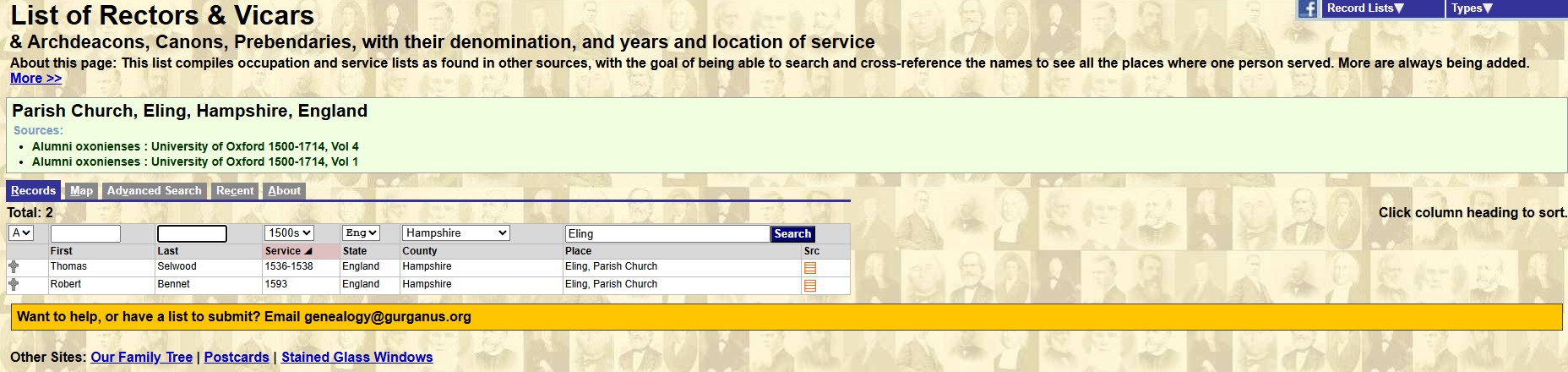

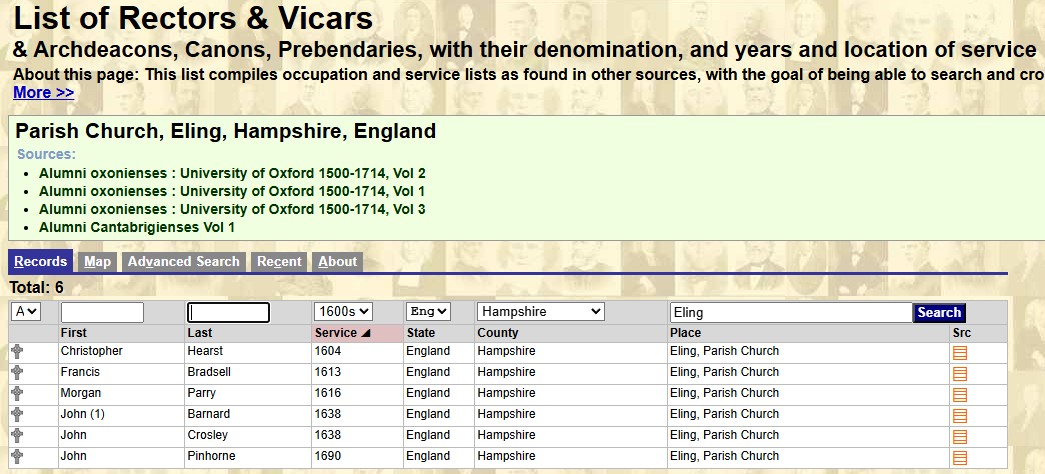

There are a few go to websites when researching a parish, some of which are listed below.

British History Online

A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 4. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1911.

GENUKI

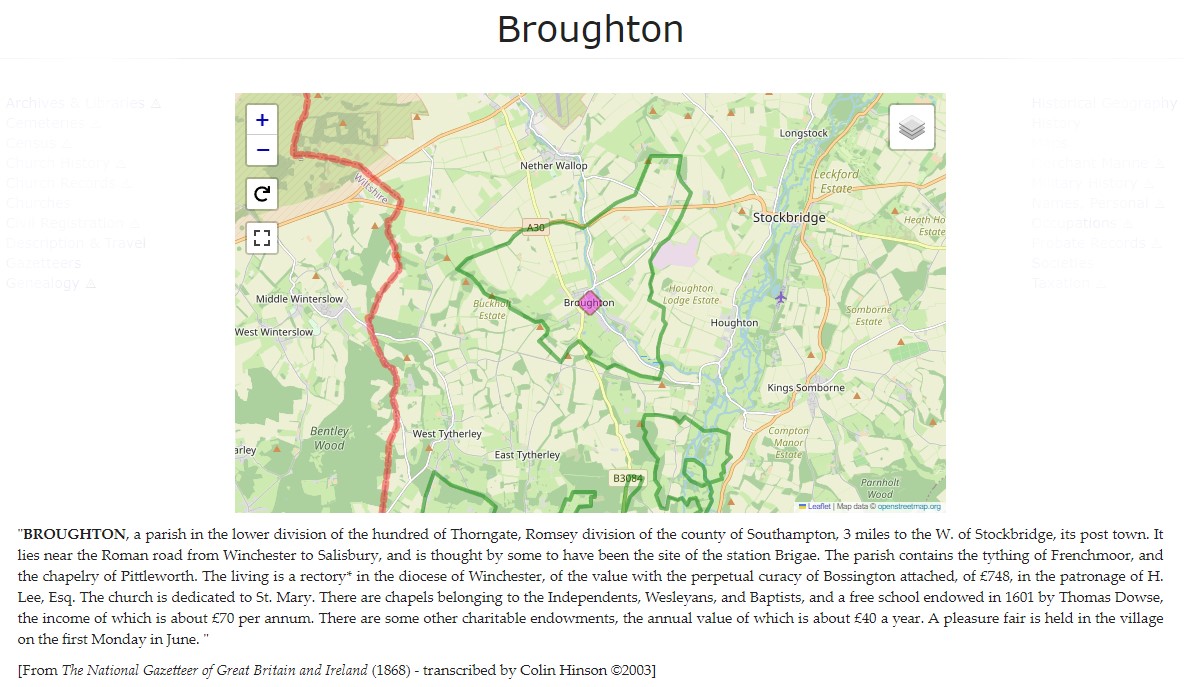

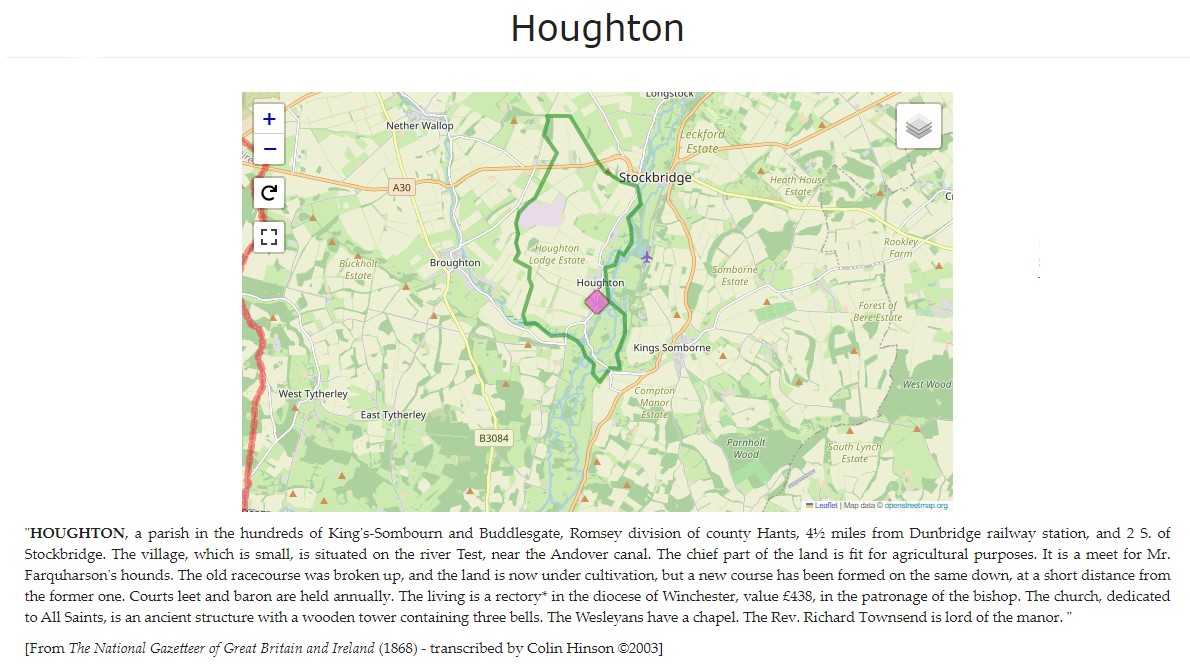

"ELING, a parish in the hundred of Redbridge, Romsey division of county Hants, 3 miles N.W. of Southampton, its post town. The Totton station, on the London and South-Western railway, is about 1; mile to the N.W. of the village. It is situated at the upper end of the Southampton Water, near the river:Test, and is of great extent, including several townships and hamlets, the principal of which are North and South Eling, Marchwood, Netley, and Totton, and the manor of Bury Farm, which last is held of the crown by the tenure of presenting to the king, on his visiting the New Forest, a brace of white greyhounds in silver couples, which ceremony was last performed in 1789, on the event of George III.'s visit to Lindhurst. "

[From The National Gazetteer of Great Britain and Ireland (1868) - transcribed by Colin Hinson ©2003]

A Vision of Britain through Time

Descriptive Gazetteer Entry for ELING

(John Marius Wilson, Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870-72))

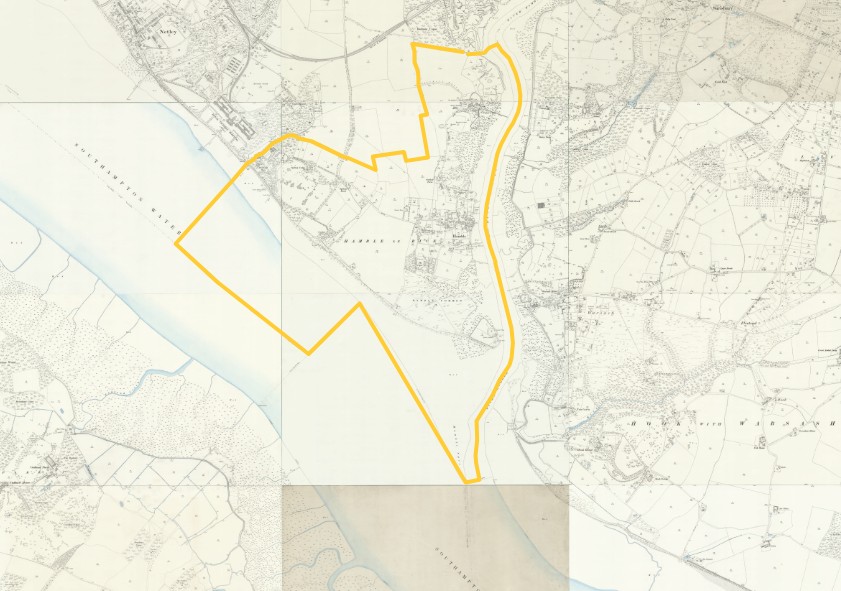

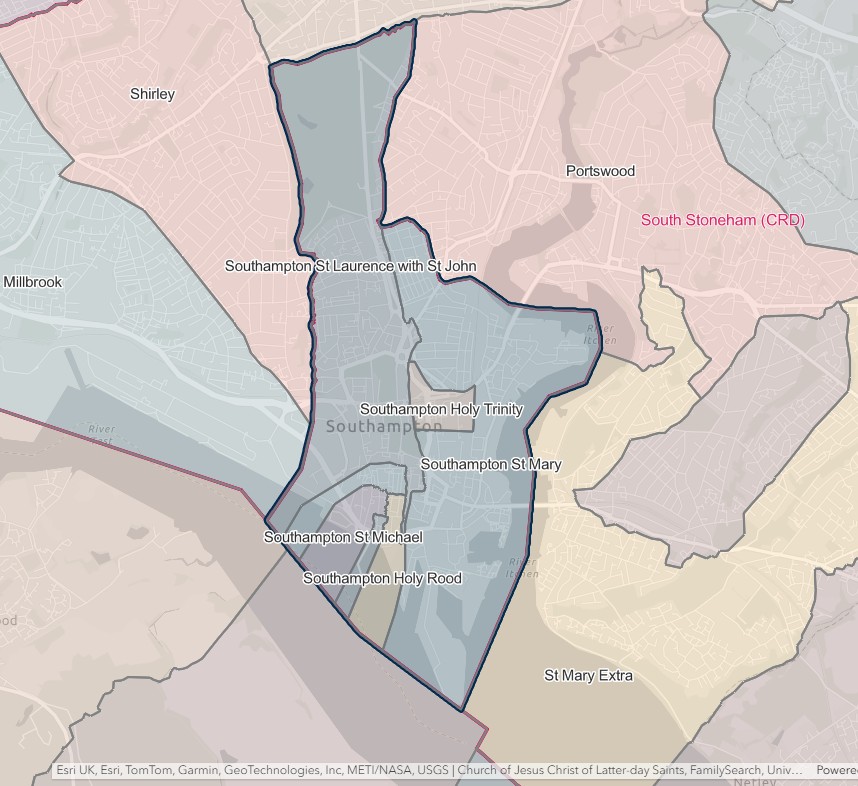

An extract of ArcGIS Church of England Parishes Map focused on the parish of Eling

The Eling One Place Study StoryMap below can also be seen in a new tab, full size, by following this link.

The place

Eling Hampshire

Eling a small village and town, as well as a large parish on the banks of the River Test opposite Southampton, and adjacent to the New Forest, in the county of Hampshire, sometimes known as Southamptonshire, or County of Southampton.

Bronze Age 1500BC

A Bronze Age Settlement to the North of the Town was discovered when the Testwood Lakes were excavated. A jetty, bridge and dagger were all found dating from that period.

The town has a history back to before Bronze Age times. It is thought the name Eling probably derives from Edlas’s people, or Edlingas as it appeared in the Domesday Book.

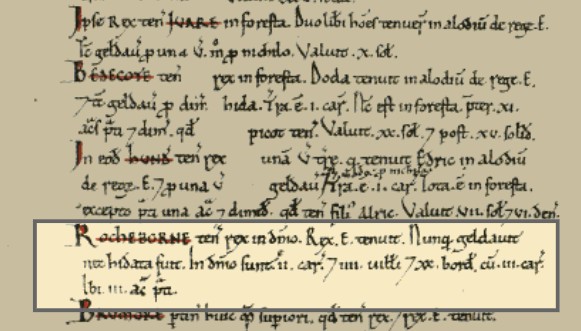

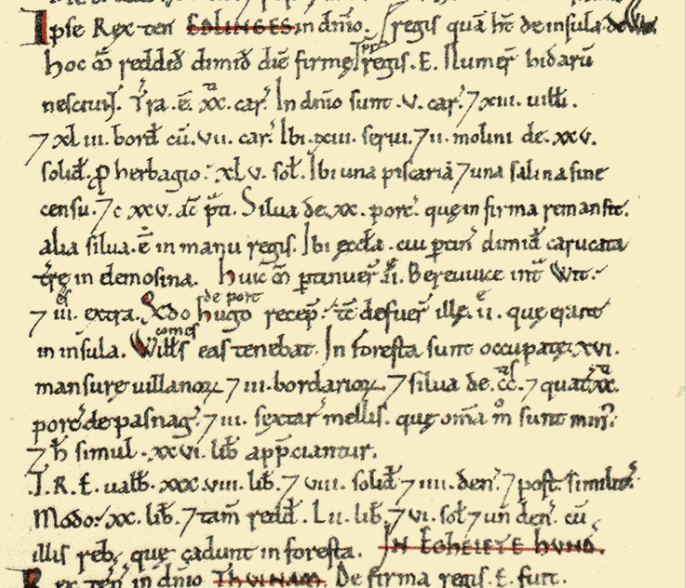

Domesday Book 1066-1086

Eling was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Redbridge and the county of Hampshire.

It had a recorded population of 69 households in 1086, putting it in the largest 20% of settlements recorded in Domesday.

![Domesday_-_Eling.jpeg]() Land of King William

Land of King William

Households

- Households: 13 villagers. 43 smallholders. 13 slaves.

Land and resources

- Ploughland: 20 ploughlands. 5 lord's plough teams. 7 men's plough teams.

- Other resources: Meadow 125 acres. Woodland 20 swine render;in Forest. 2 mills, value 1 pound 5 shillings. 1 fishery. 1 salthouse. 1 church. 0.5 church lands.

Valuation

- Annual value to lord: 20 pounds in 1086; 38 pounds 8 shillings and 2 pence when acquired by the 1086 owner; 38 pounds 8 shillings and 2 pence in 1066.

Owners

- Tenant-in-chief in 1086: King William.

- Lord in 1086: King William.

- Lord in 1066: King Edward.

Other information

- Partially waste in 1086.

- Phillimore reference: Hampshire 1,27

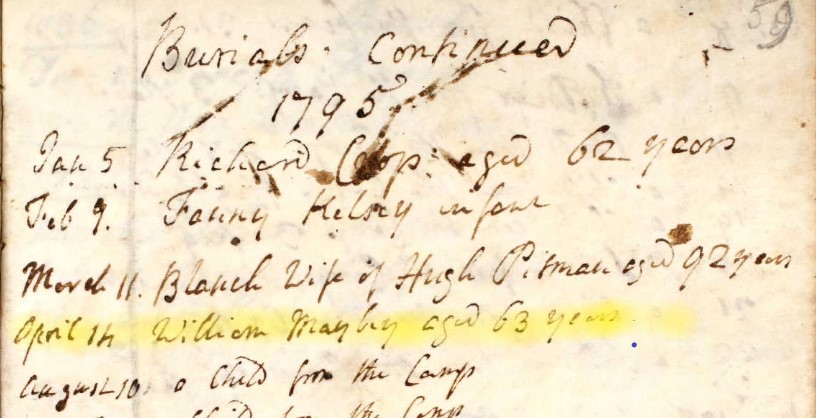

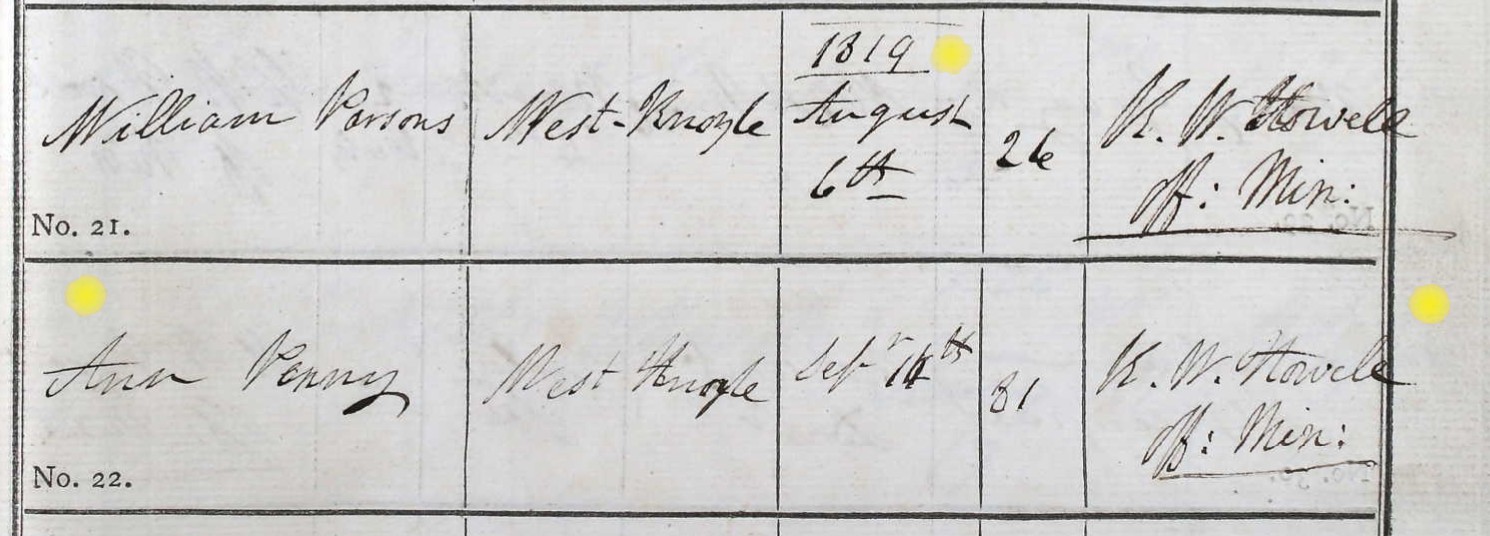

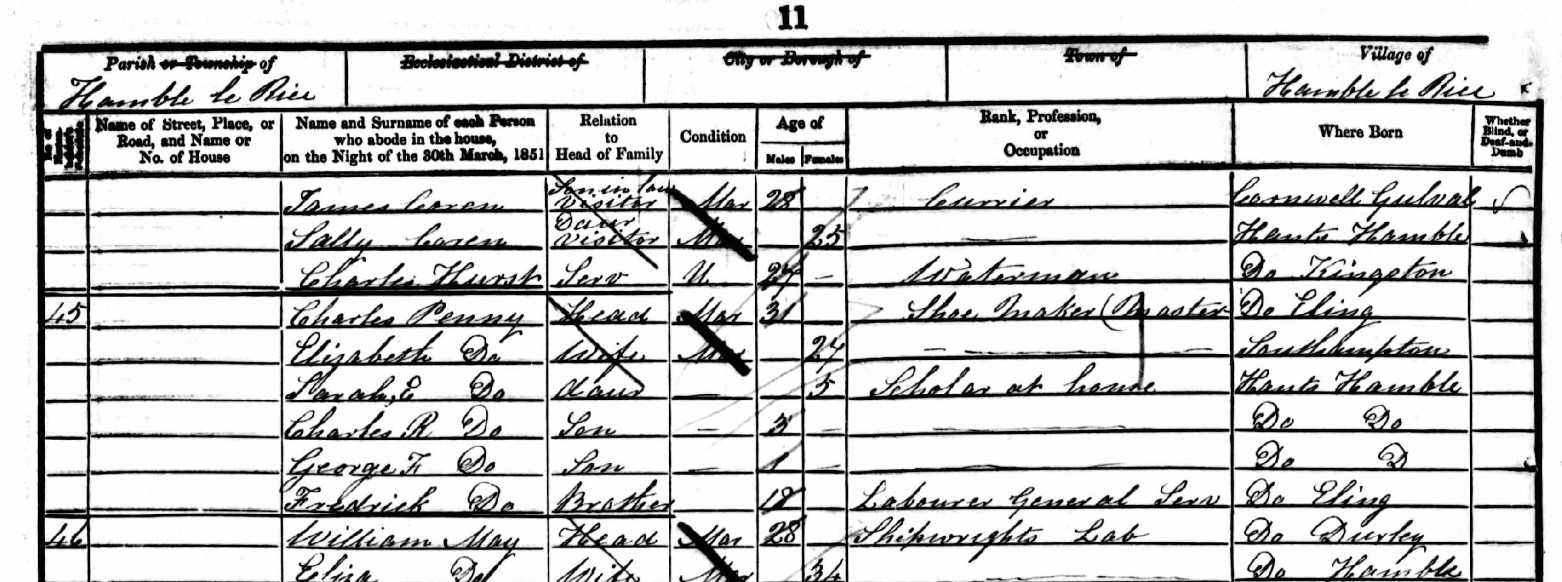

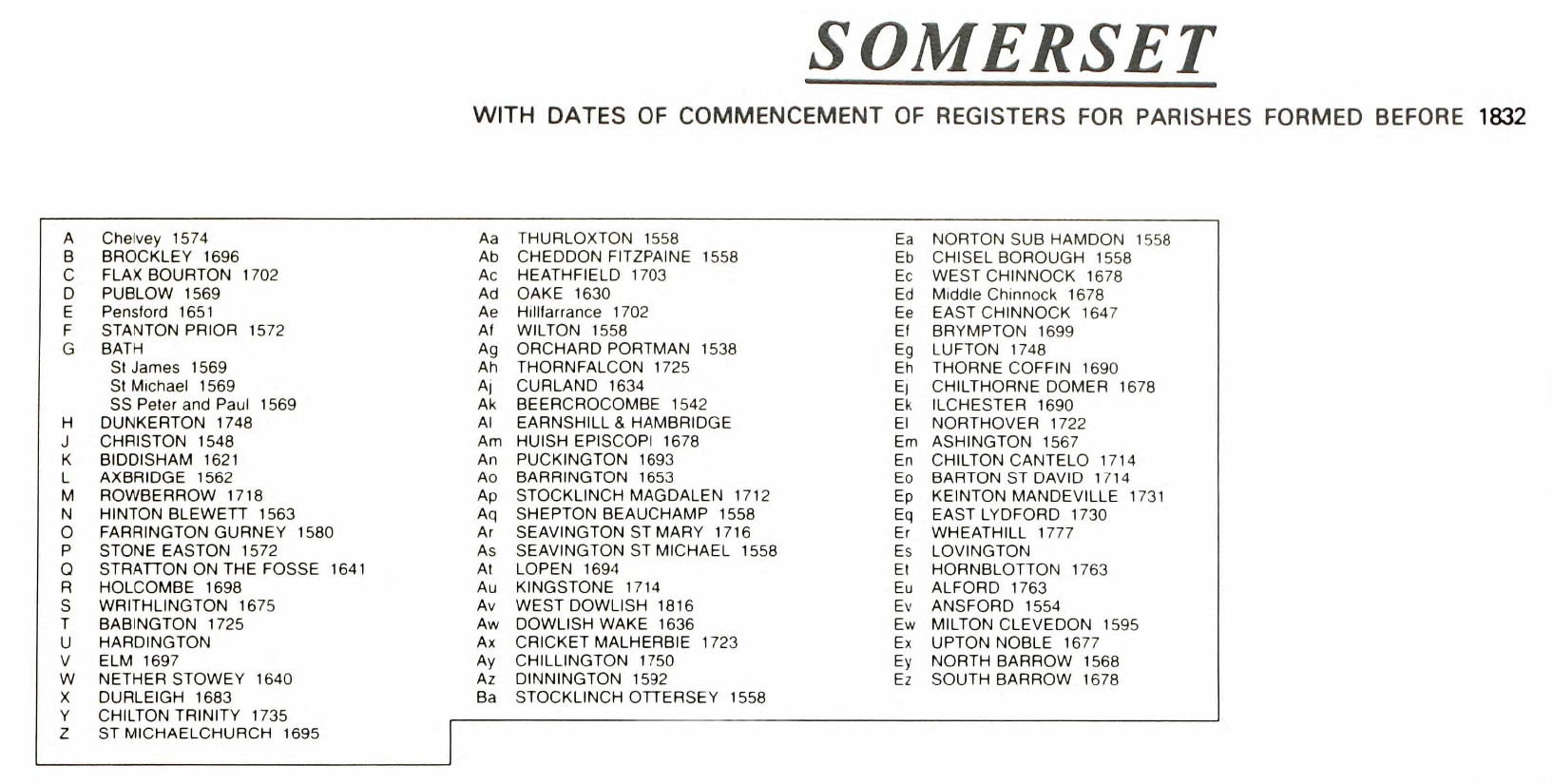

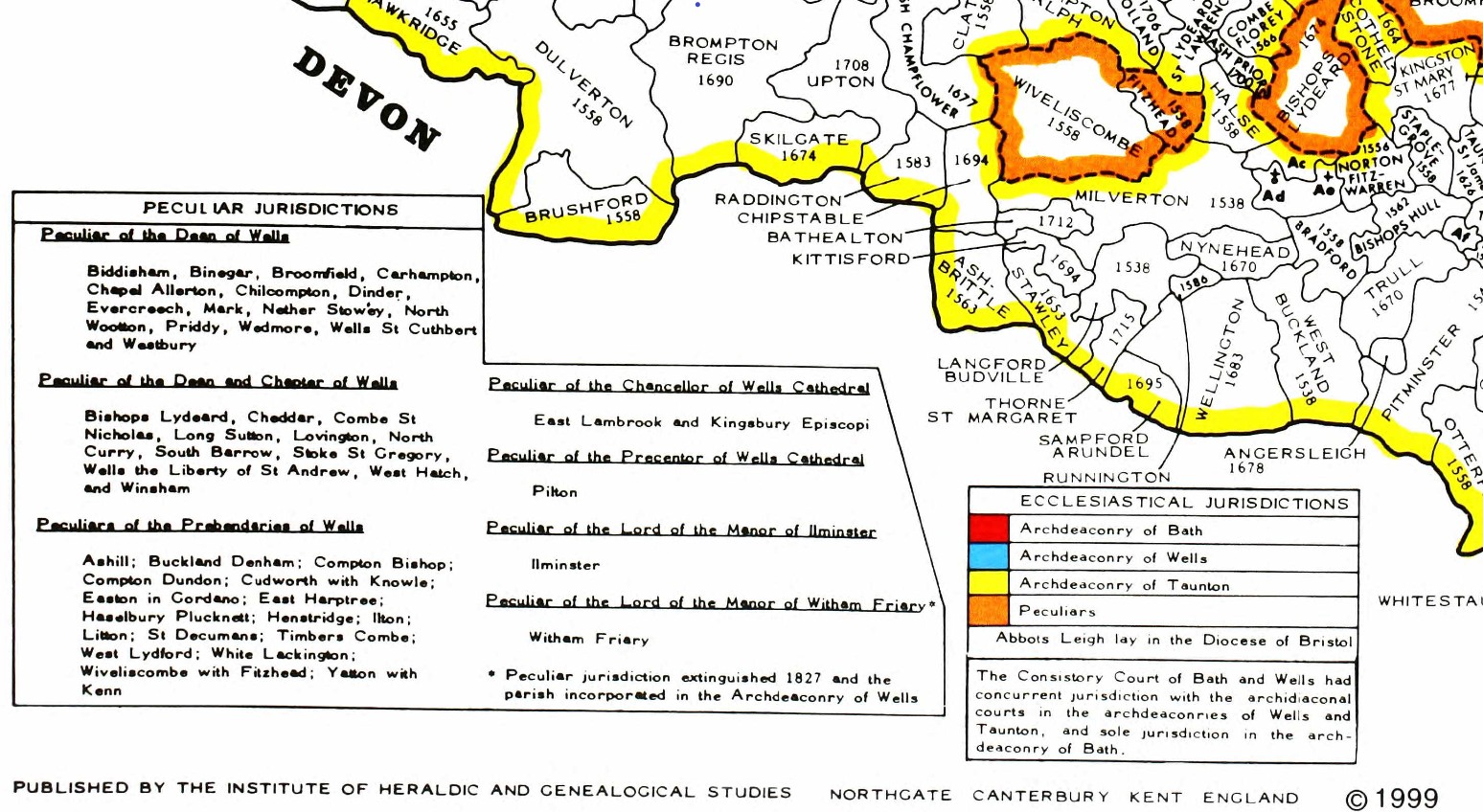

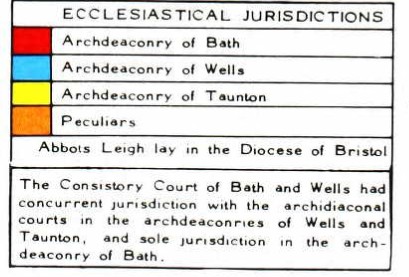

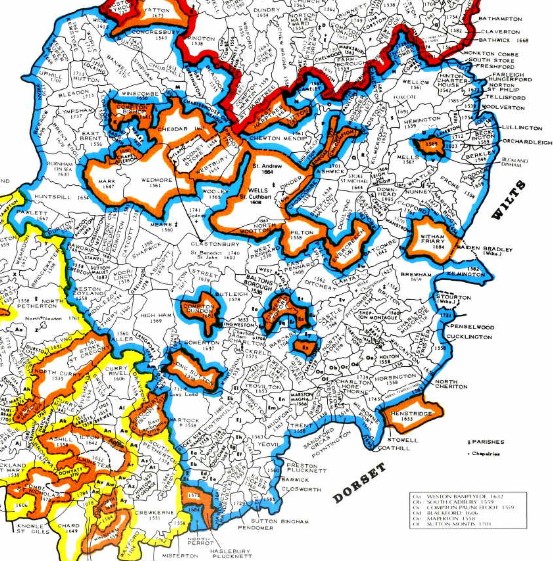

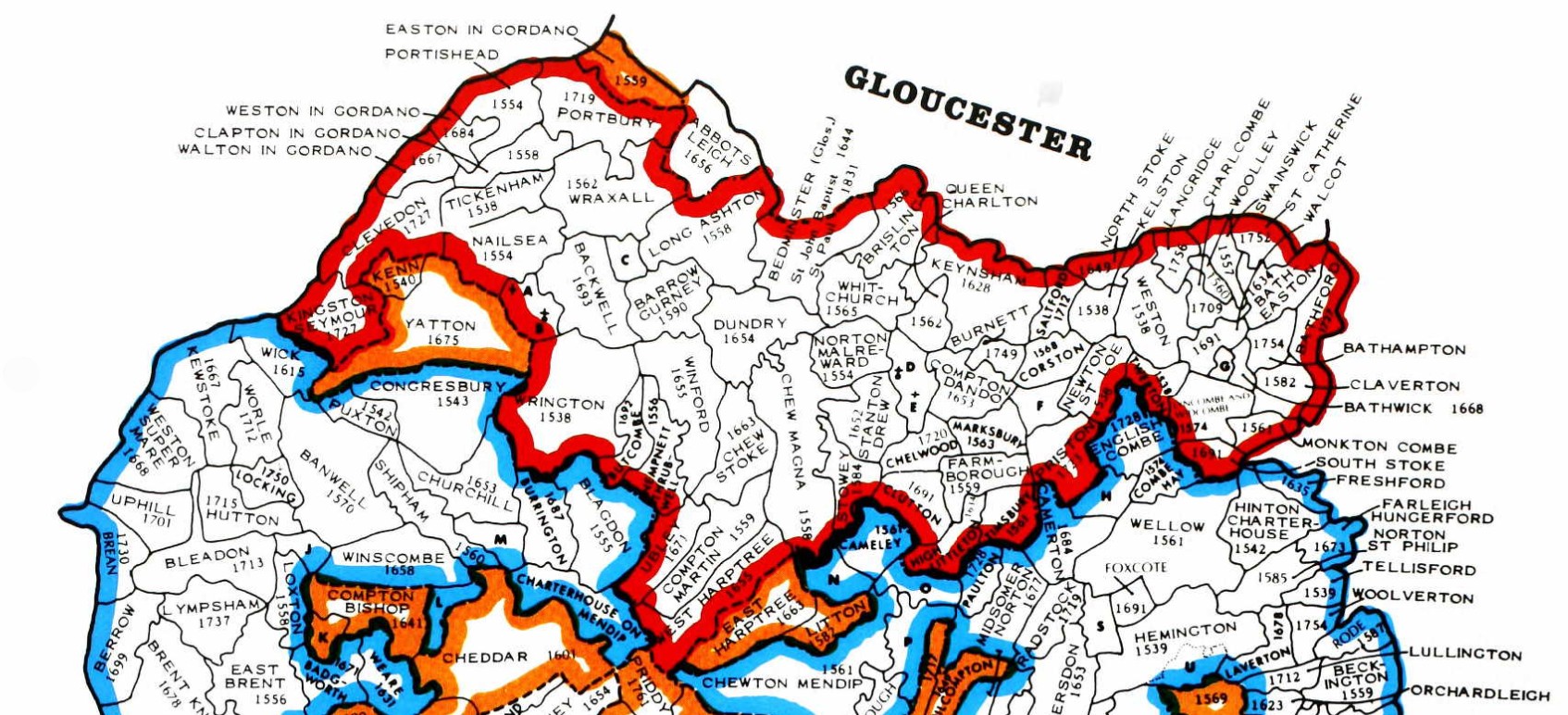

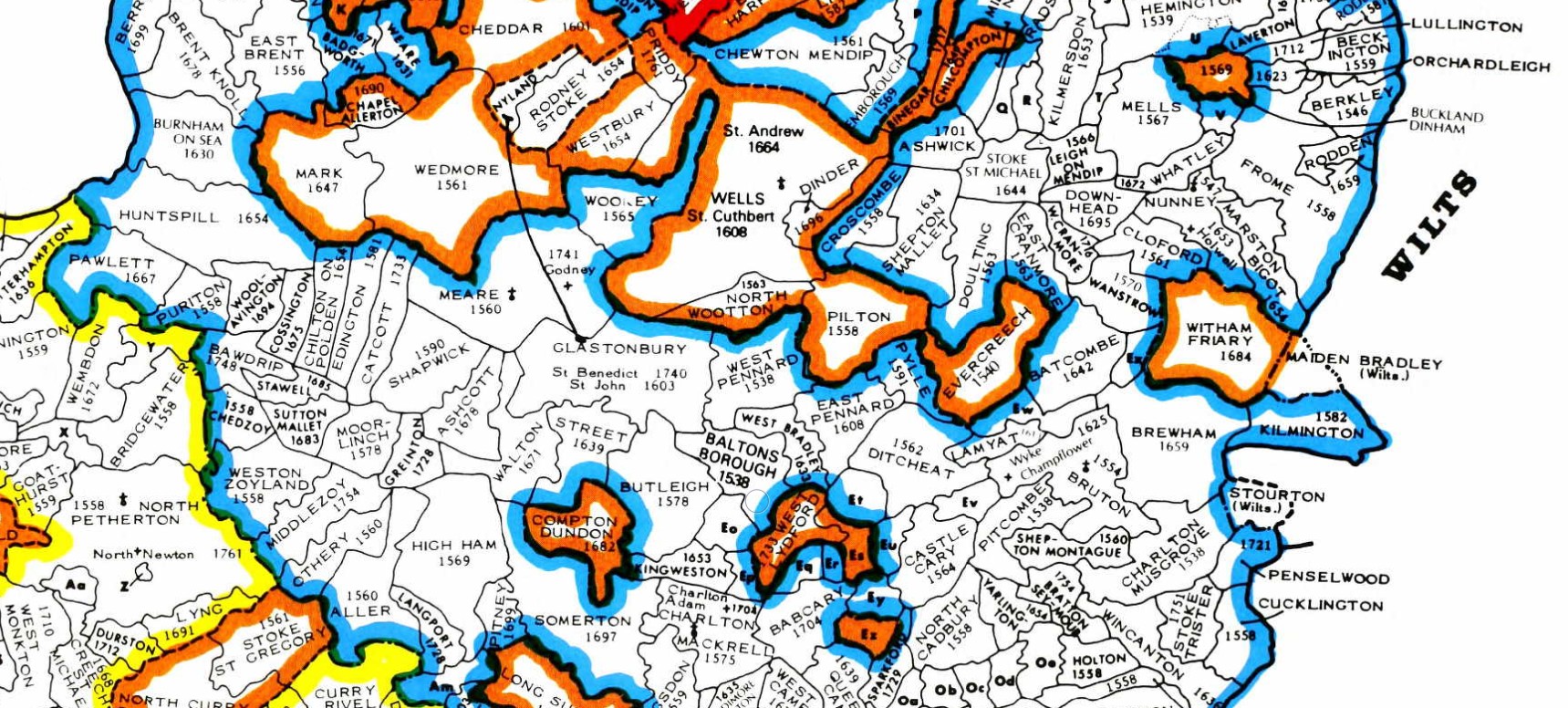

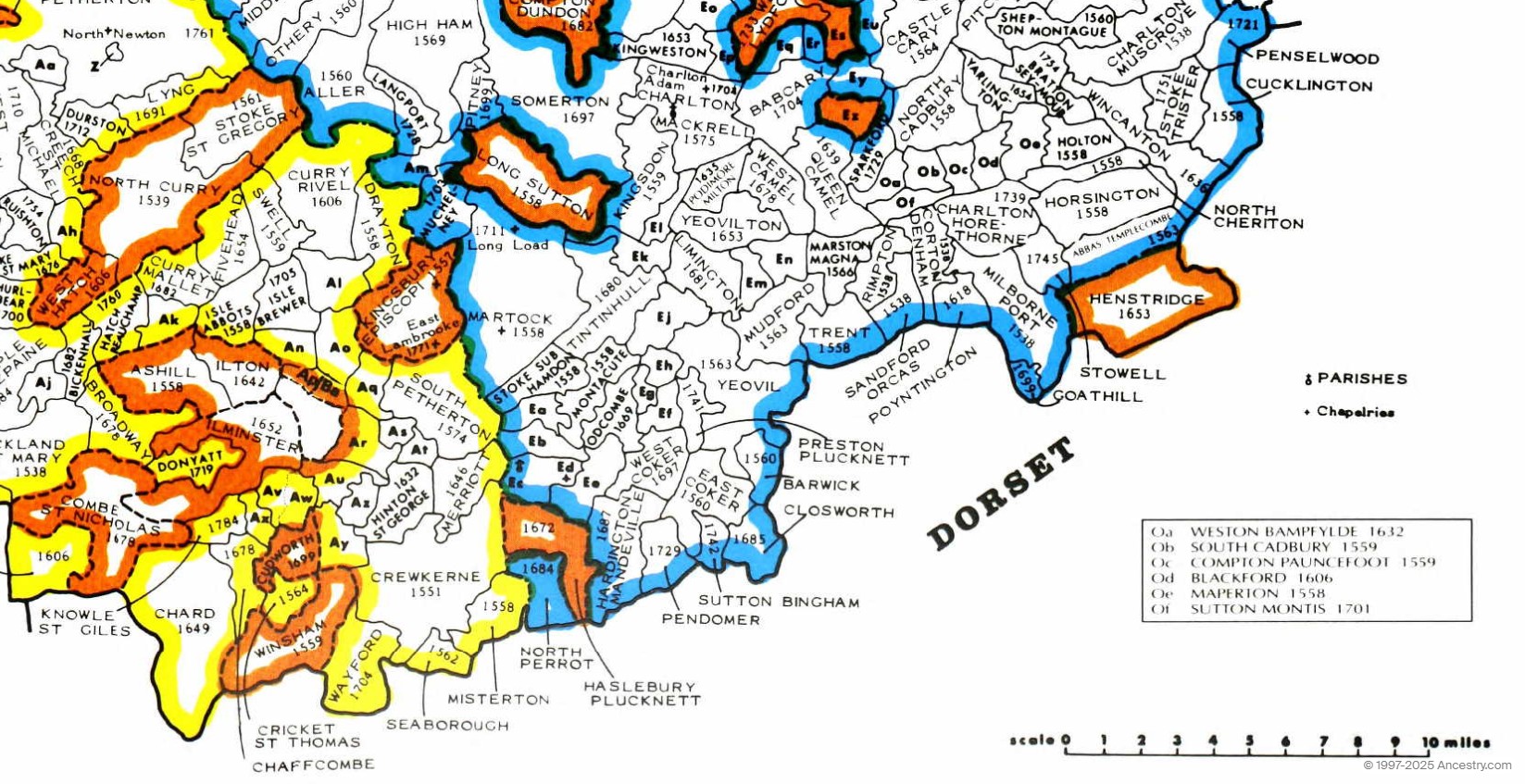

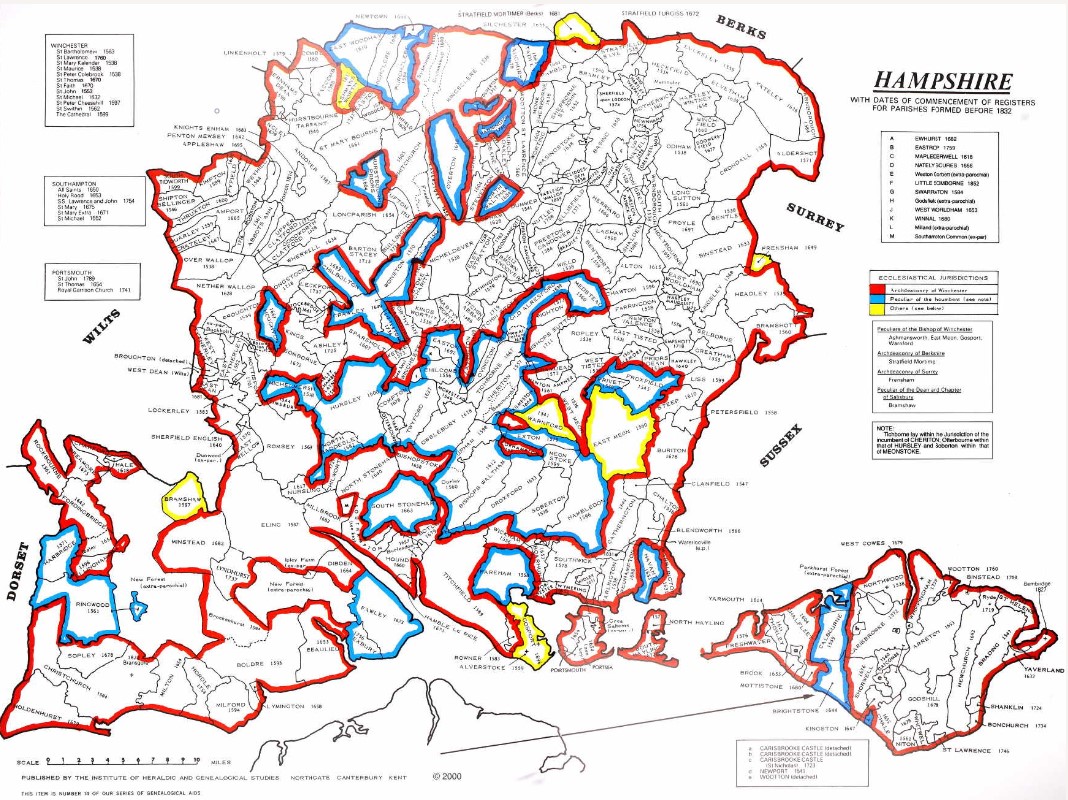

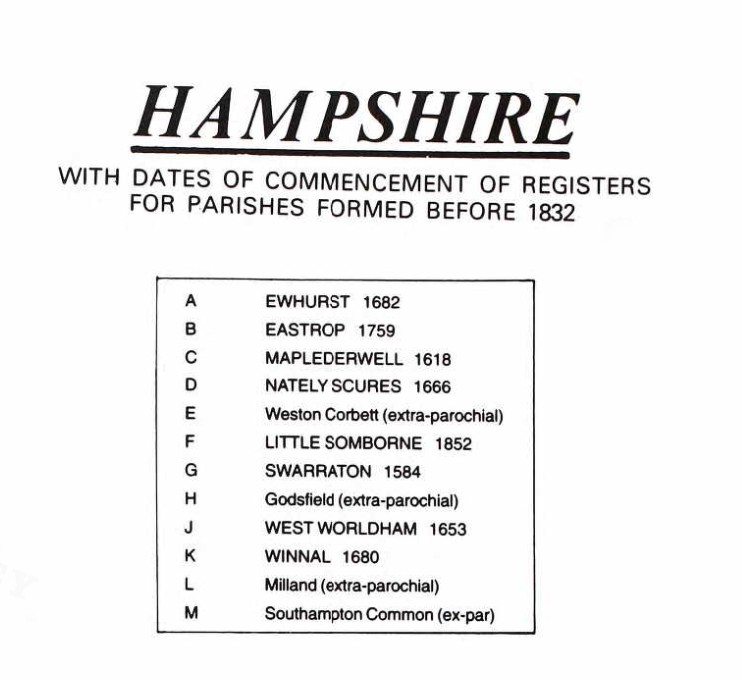

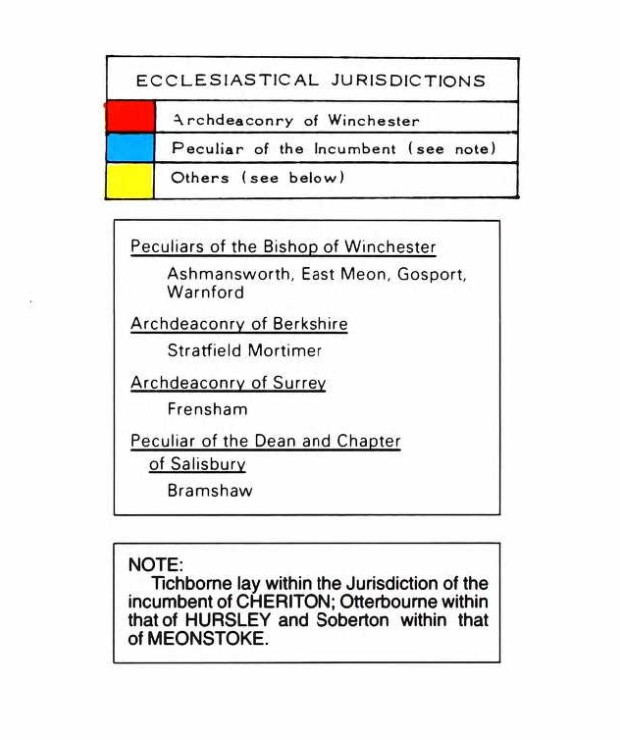

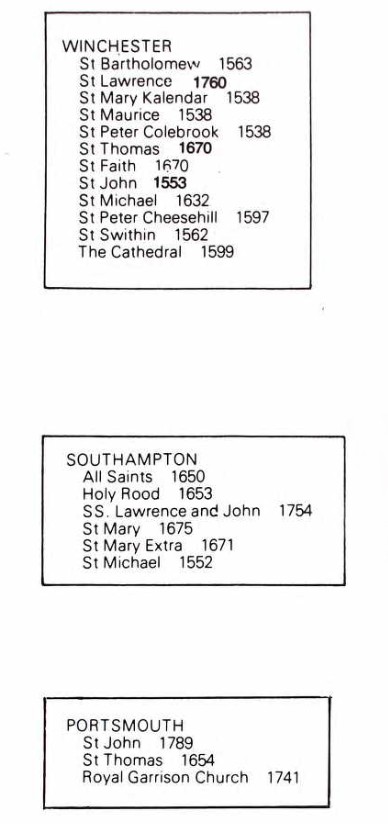

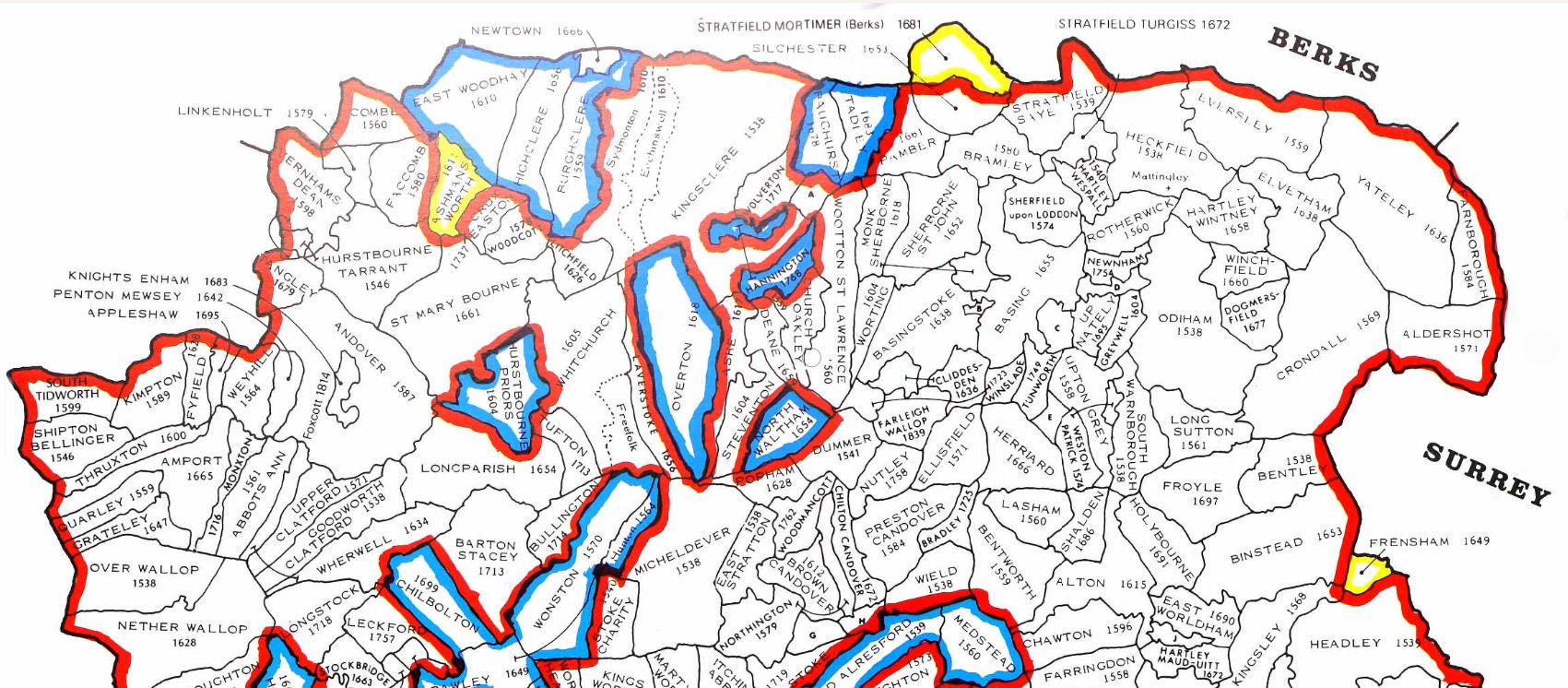

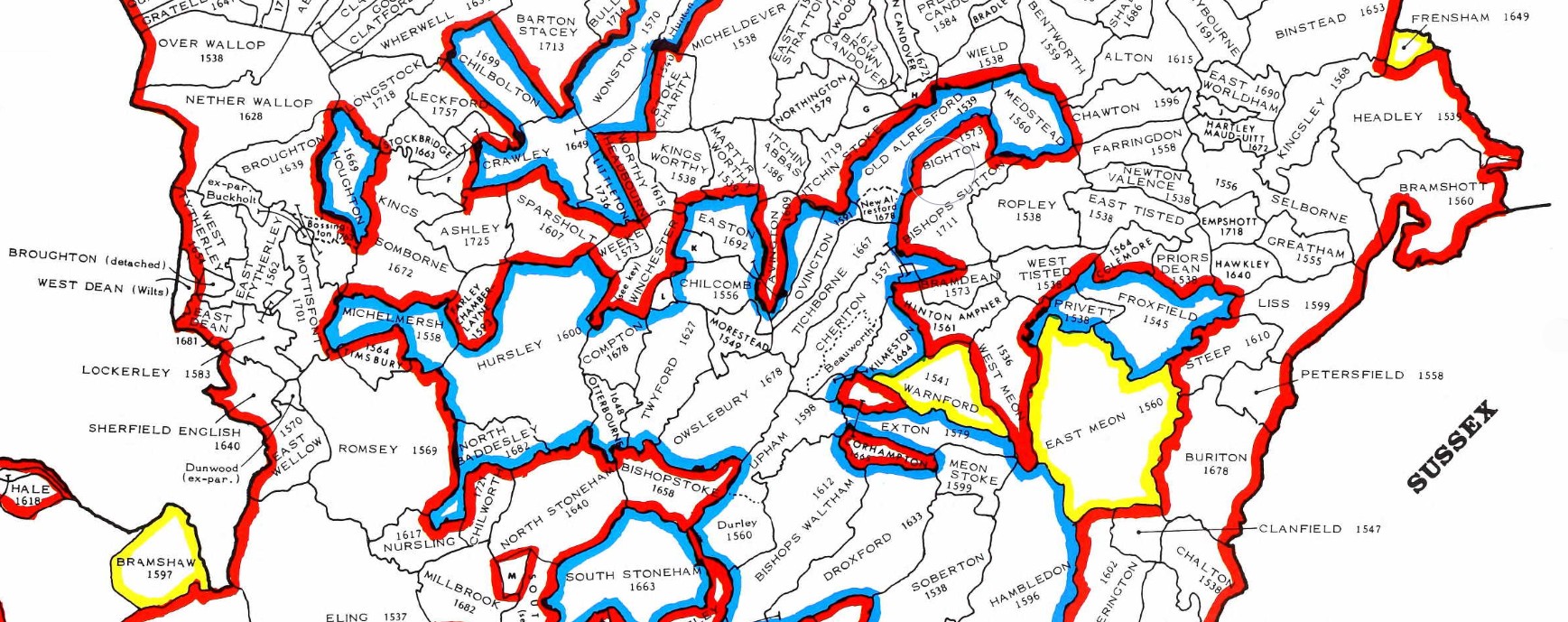

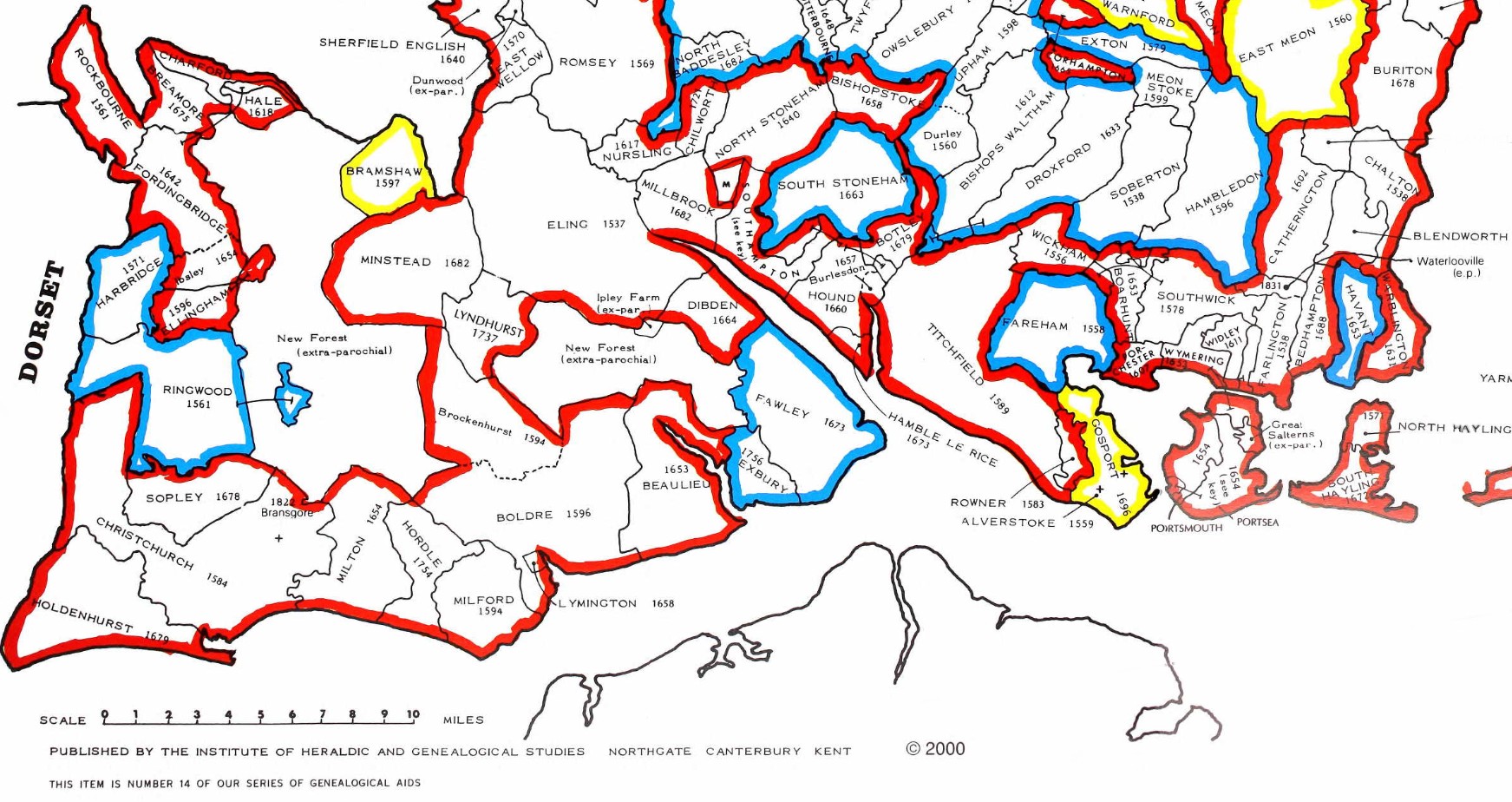

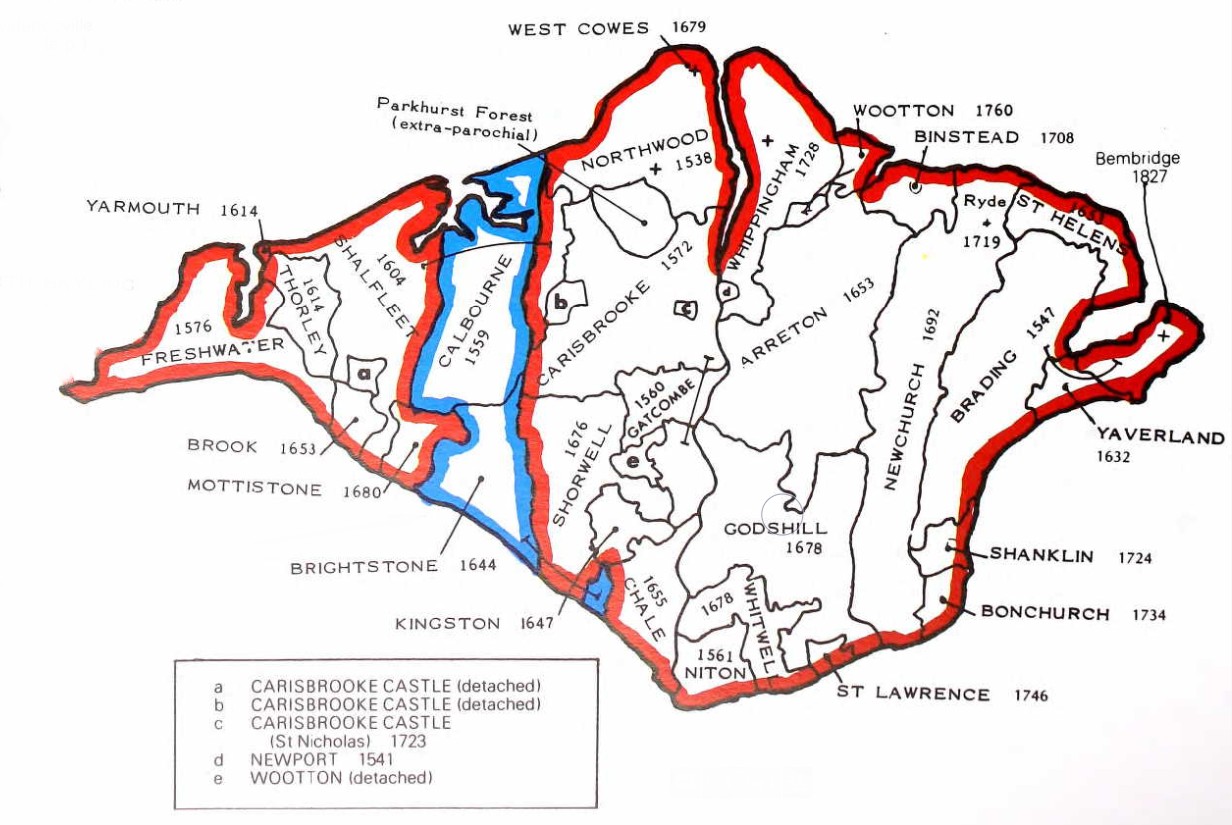

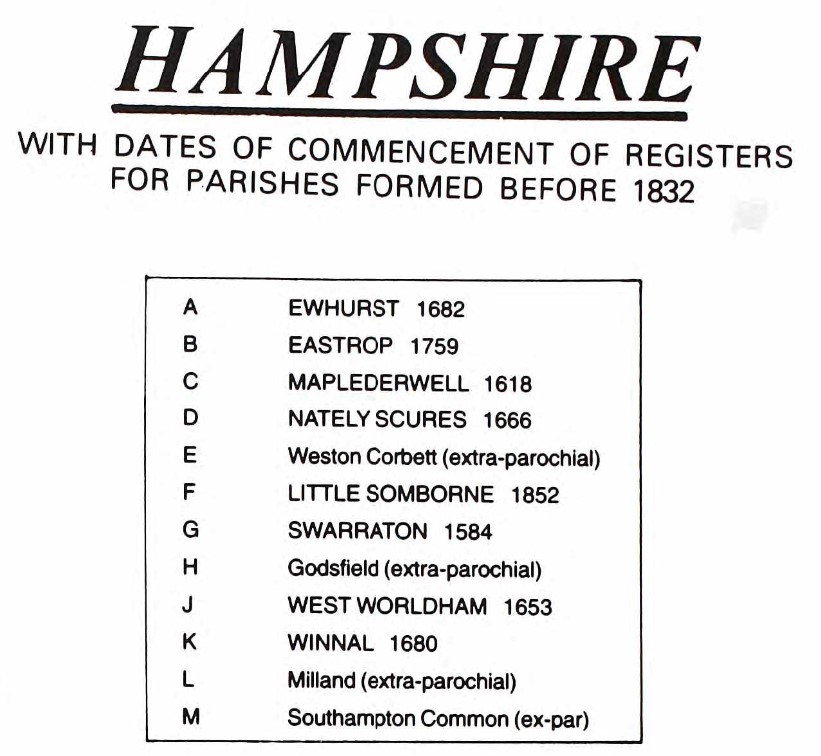

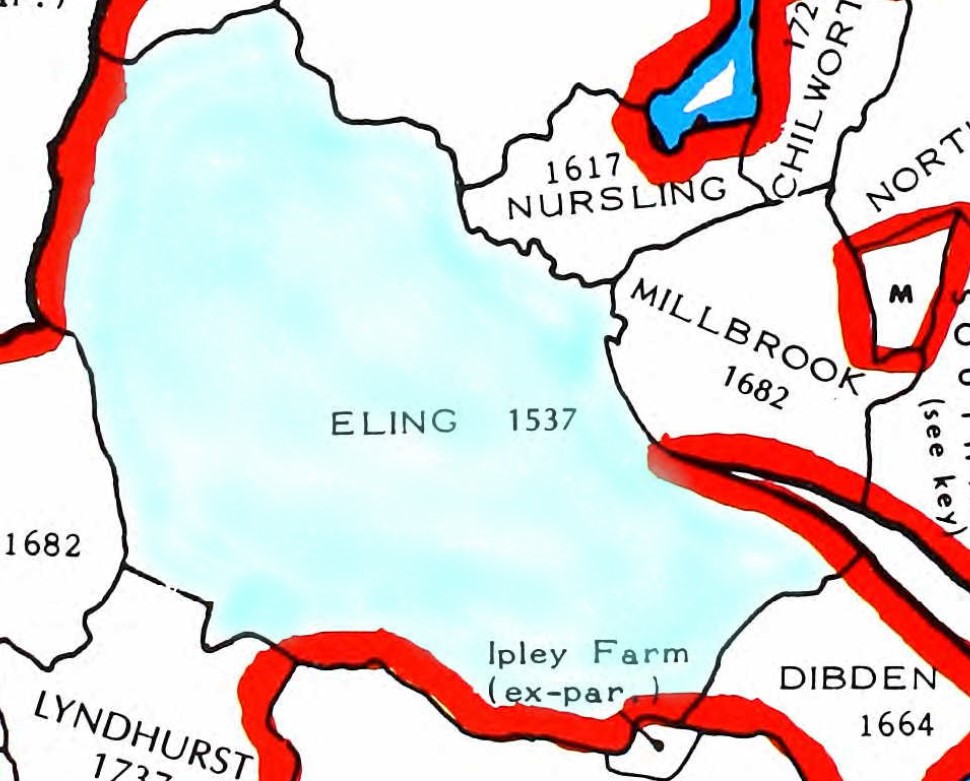

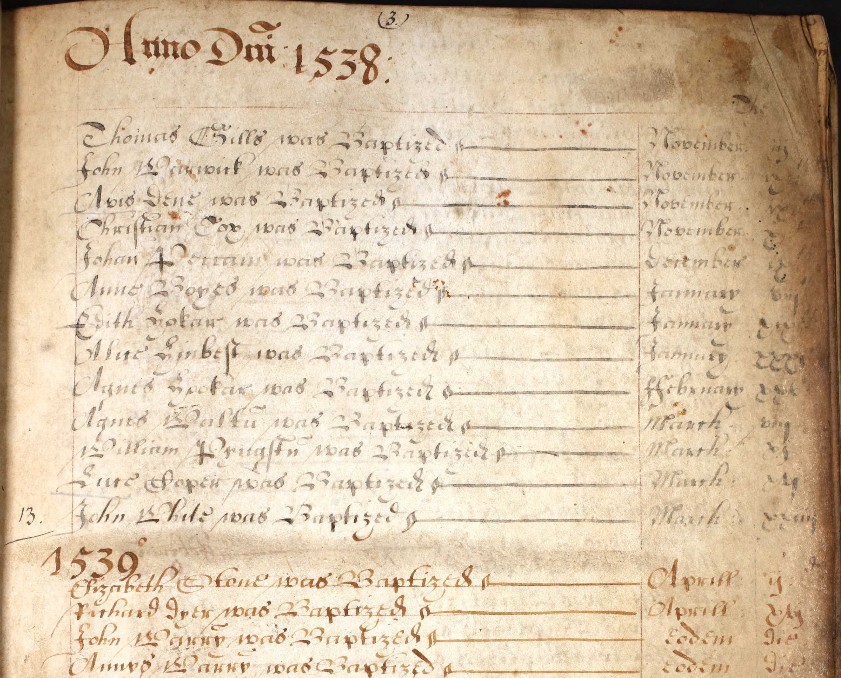

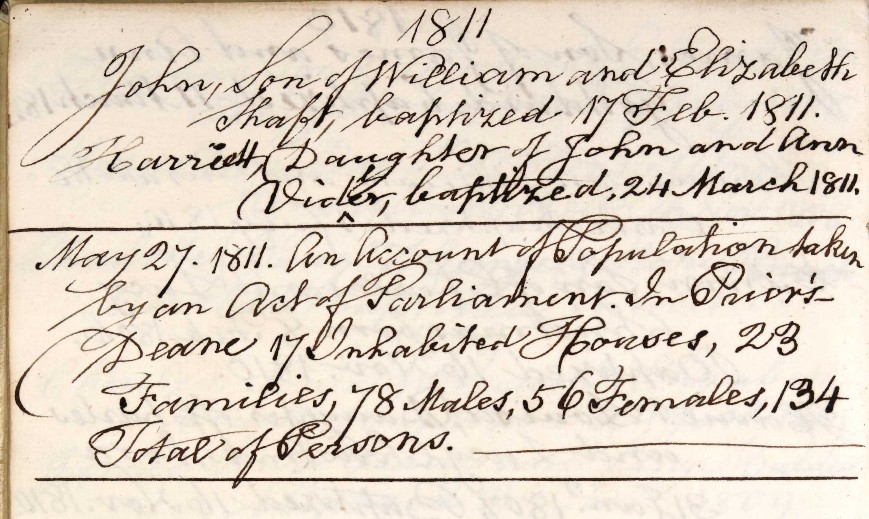

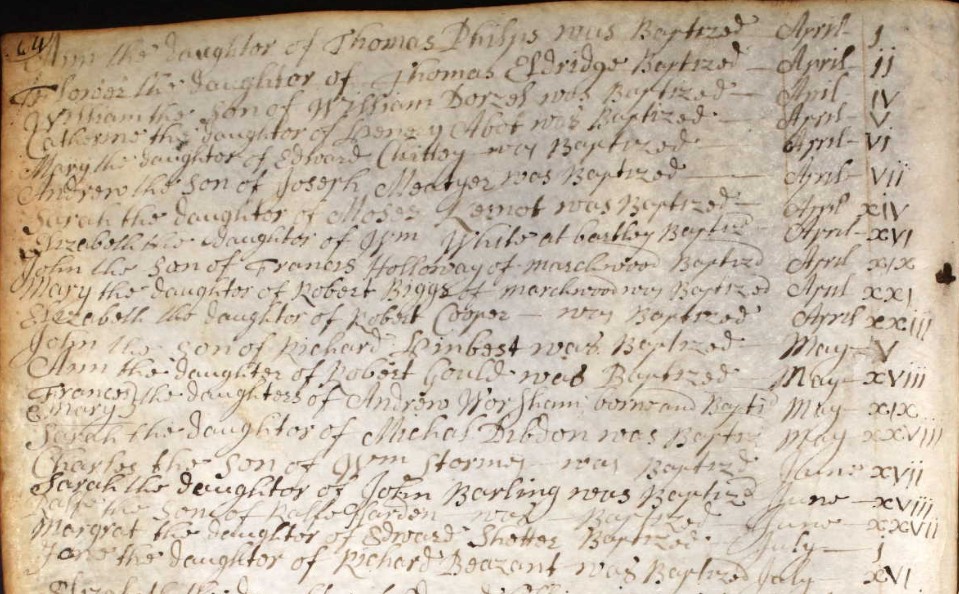

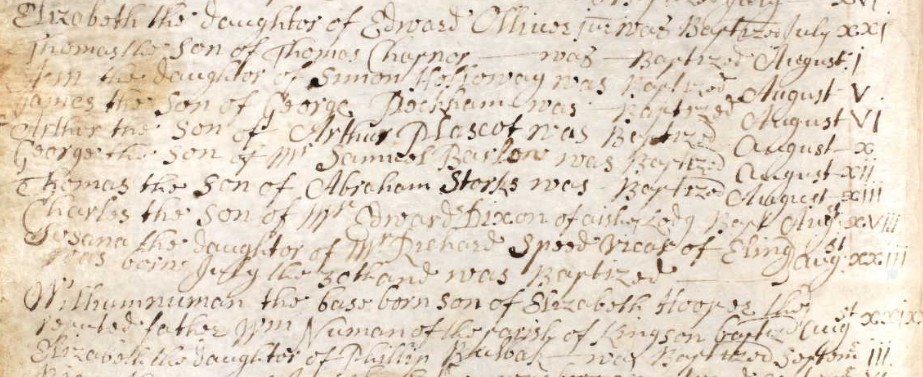

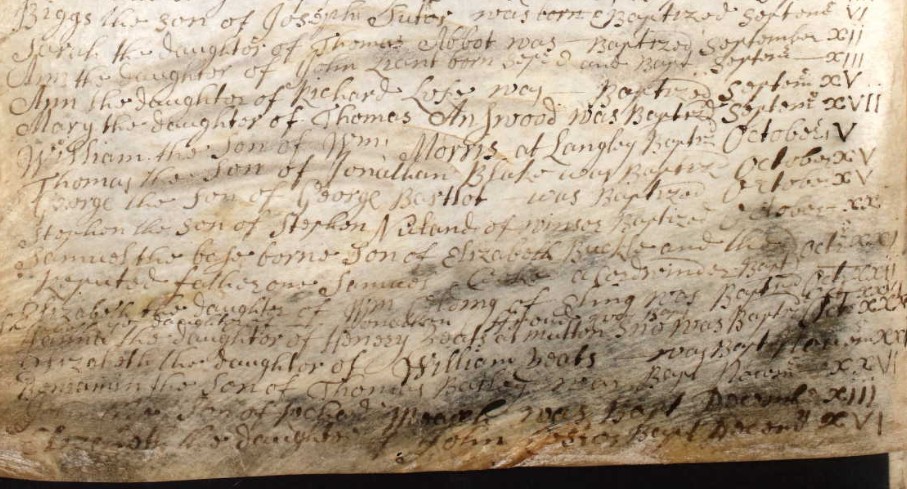

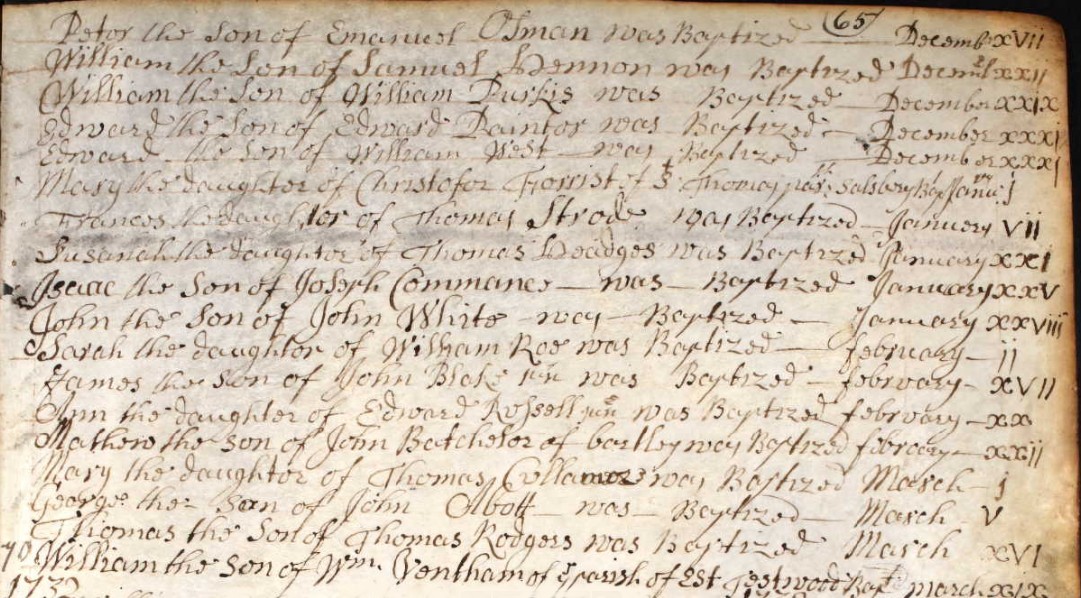

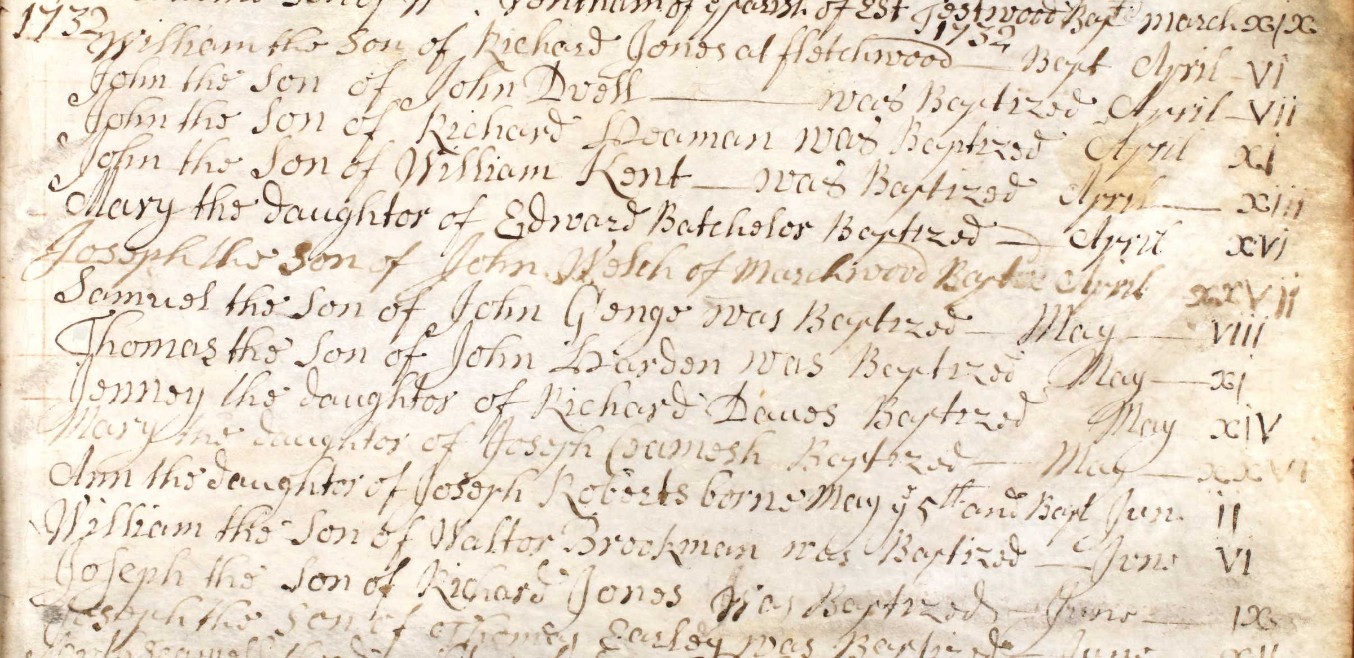

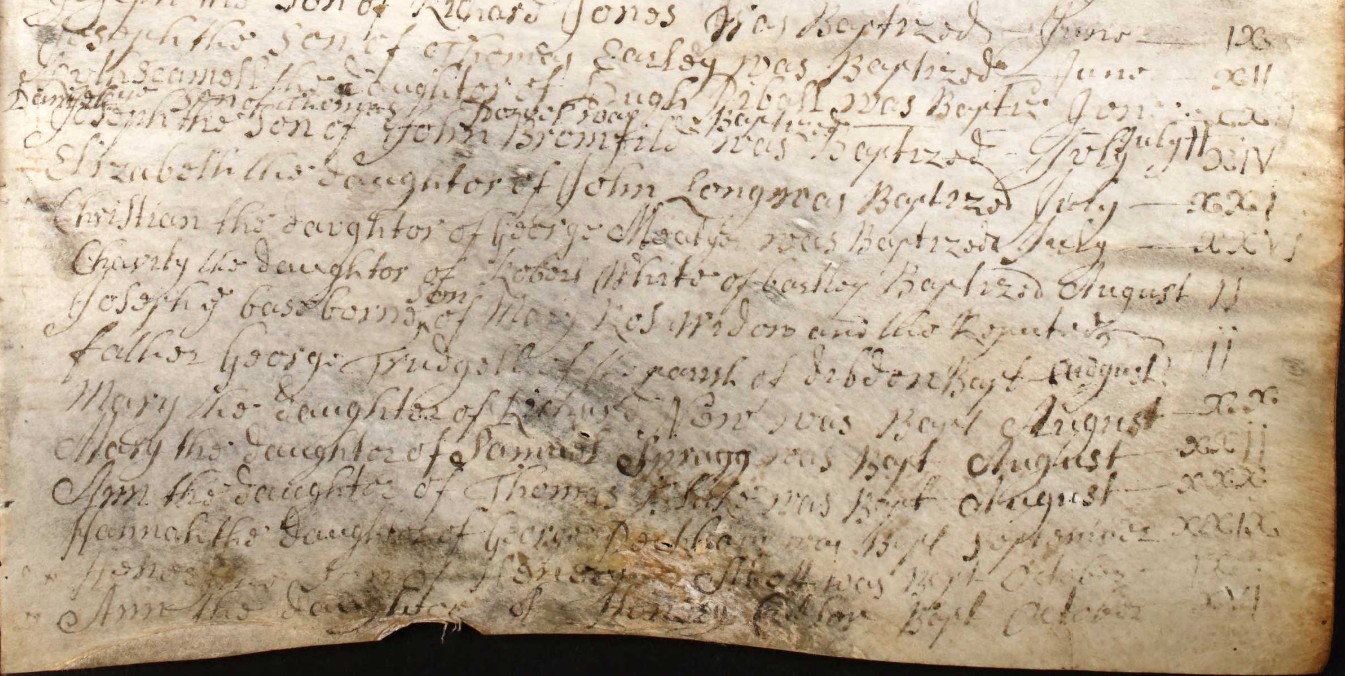

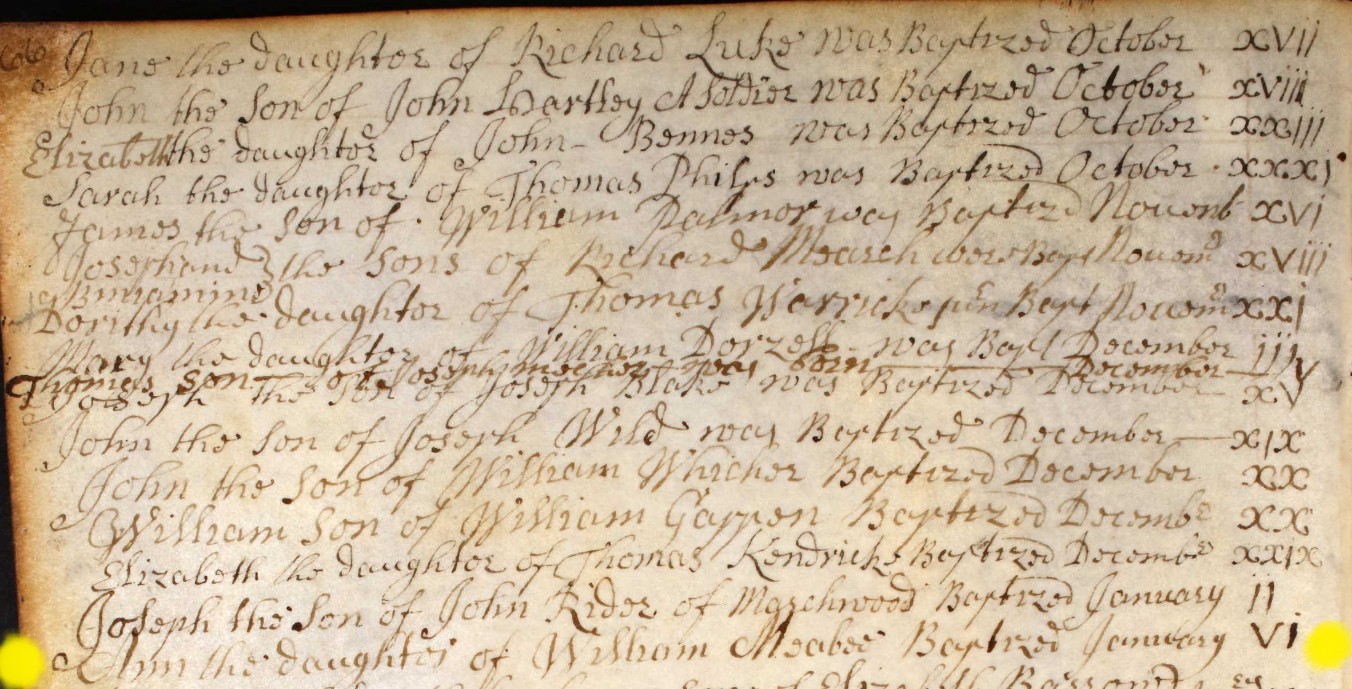

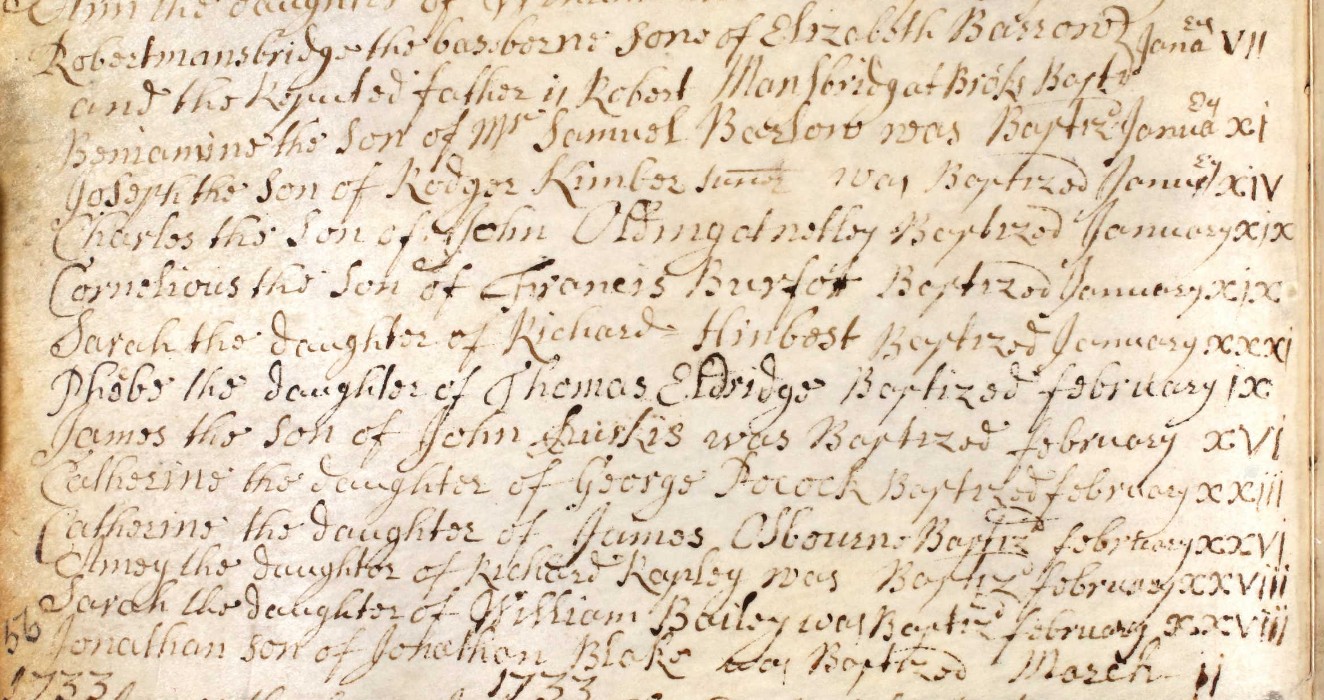

Hampshire Parishes - Eling Parish 1537

Original data;

Smith, Cecil R. Humphery. The Phillimore Atlas and Index of Parish Registers. Digitized images. Institute of Heraldic and Genealogical Studies, Canterbury, Kent, England. From Ancestry

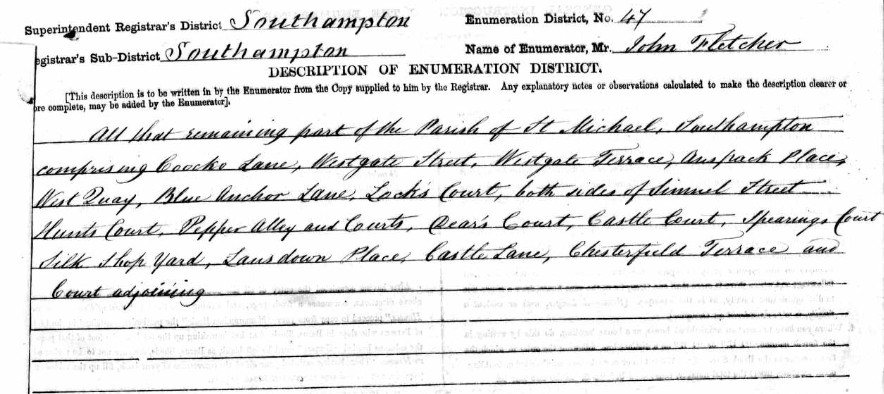

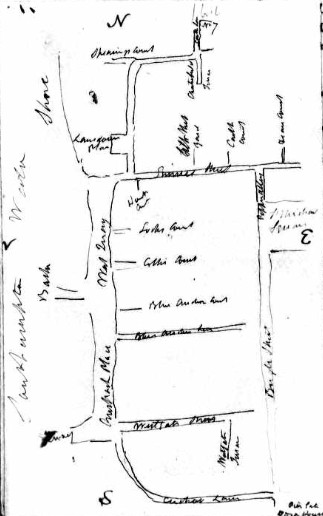

County map of Parishes - Hampshire

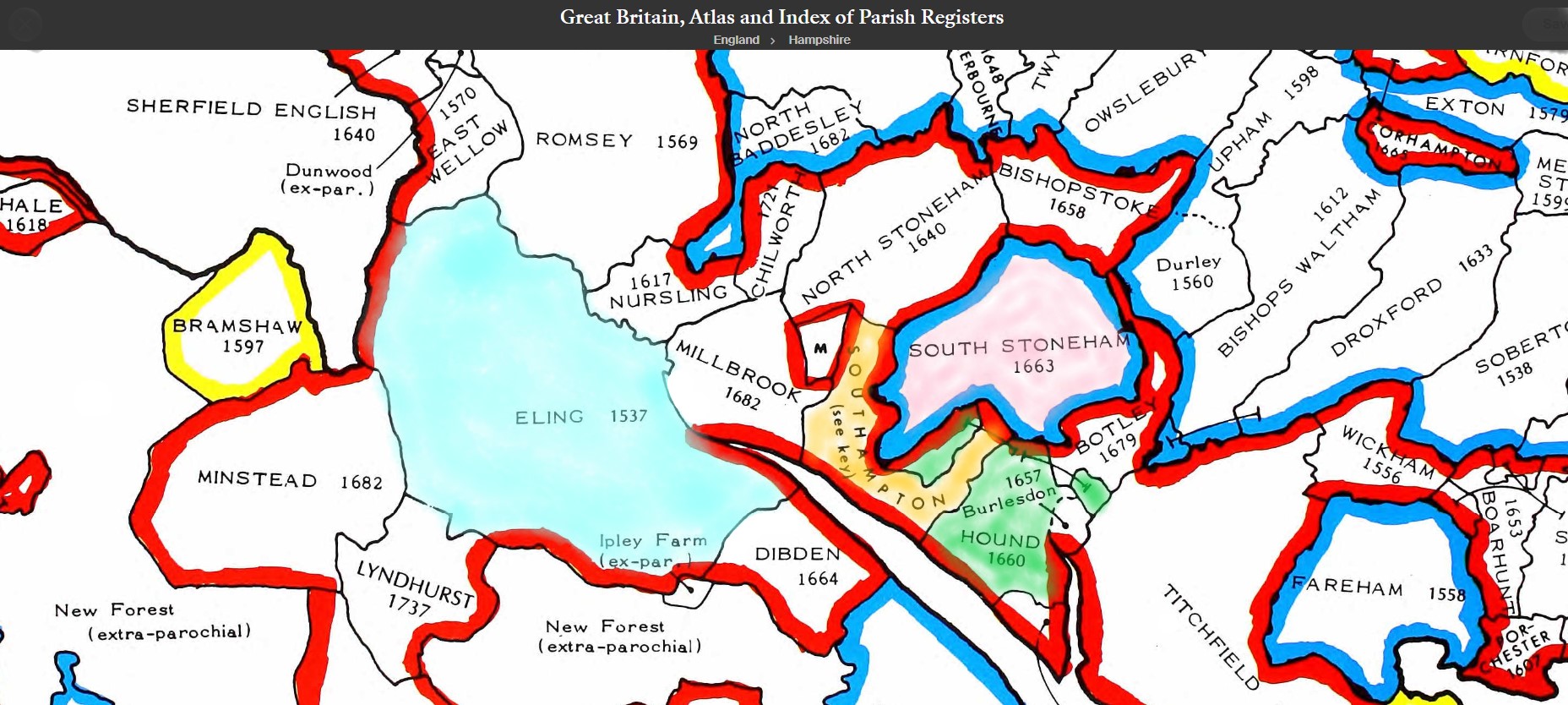

Extract from Great Britain, Atlas and Index of Parish Registers, from Ancestry

Same map but in more detail

The same map but zoomed in and split into four parts for ease of use.

There is a vertical overlap on each segment to try to avoid the difficulty of interpreting the information, reading at the joints.

At one time this was done with mouse rollover, but that no longer consistently works on all browsers, so back to static.

The above map is an extract of the The Phillimore Atlas and Index of Parish Registers for Hampshire. Of particular interest, the Parishes of Eling - 1537, Southampton, Hound 1660, and South Stonham 1663.

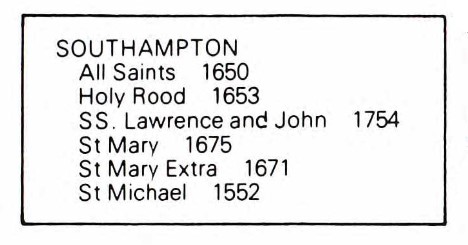

Southampton contains the following parishes;

- All Saints - 1650

- Holy Rood - 1653

- SS, Lawrence and John, sometimes written as St Lawrence and St John - 1754

- St Mary - 1675

- St Mary Extra - 1671 (Other side of the River Itchen)

- St Michael - 1552

- Southampton Common, marked as M, extra-parochial.

The dates are not when the parishes were formed but as it states by the County Title, the dates of the commencement of Registers of Parishes formed before 1832.

I think that may be expanded to dates of registers still in existence.

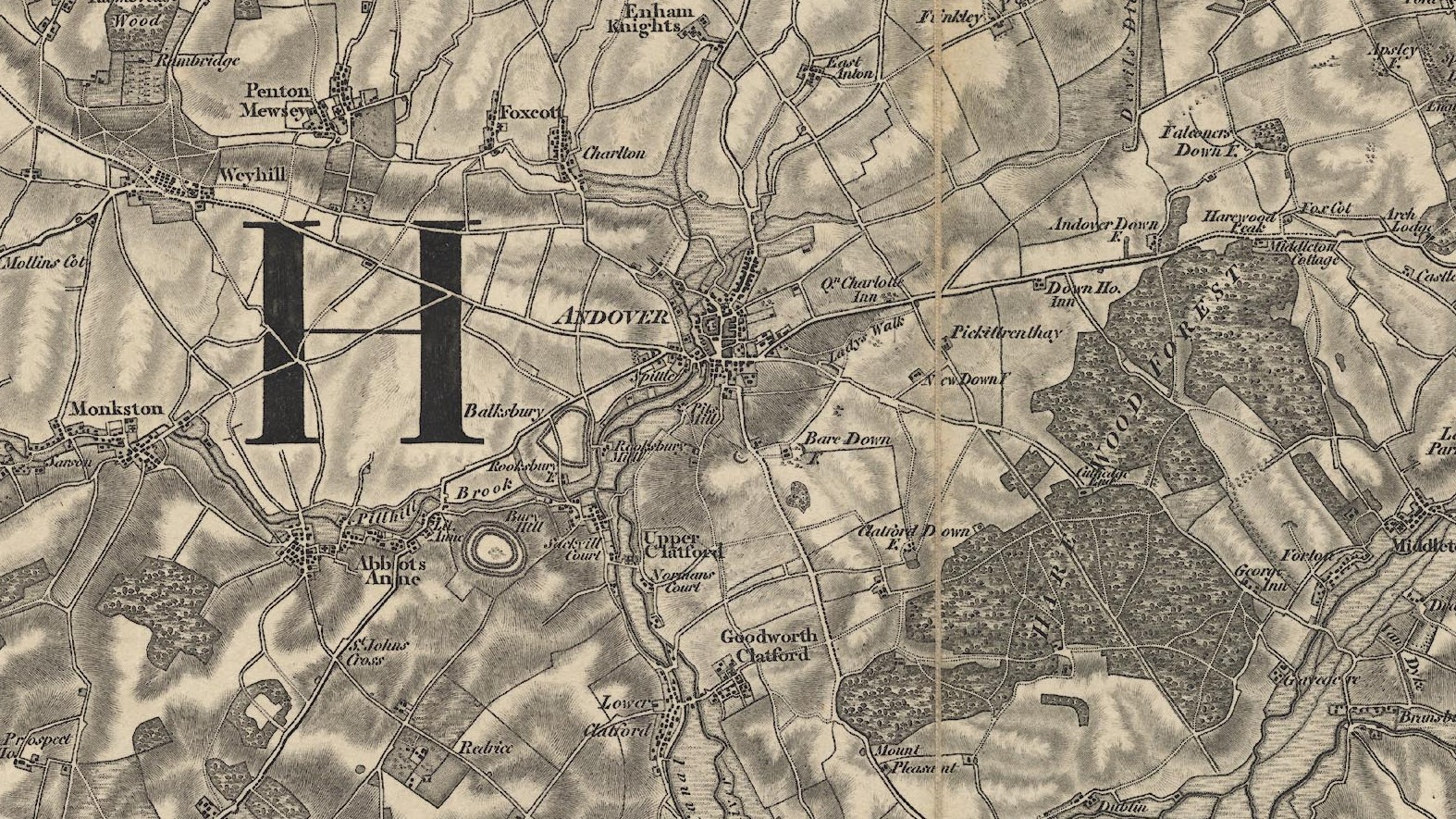

Old Hampshire Maps

The website for Old Hampshire Maps and Other Historic Resources is a most excellent source of information which I often refer to.

I normally click on the top left icon, Old Hampshire Mapped, but believe that the one next to it on the right is more extensive and gets to the same maps and more.

This section could be called an indulgence to my lifelong fascination with maps and travel. Maps can tell you so much more than just how to get from A to B. Maps over time add to so much more.

Generally, the maps refer to Eling the settlement as opposed to the much larger parish. Something in the history must have given Eling some significance.

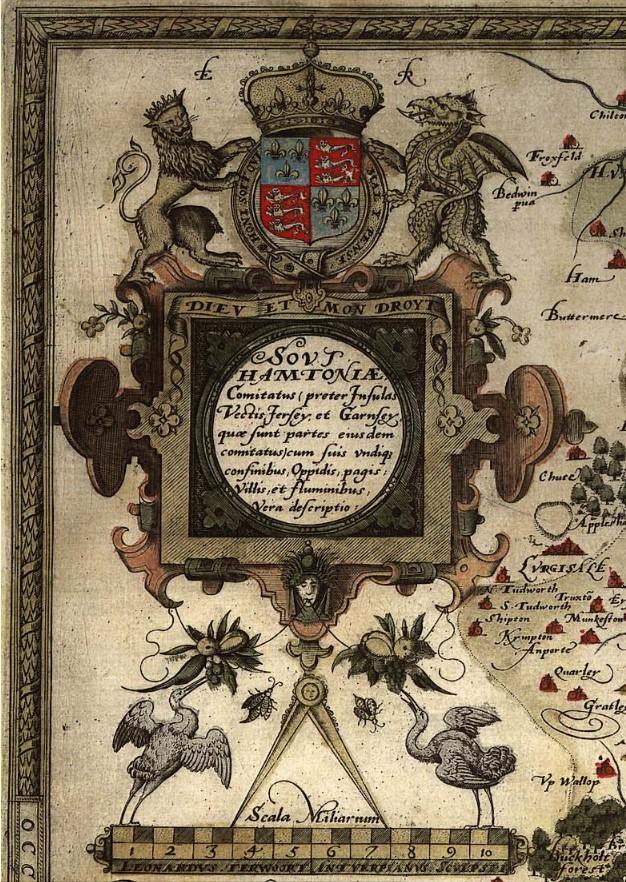

Saxton 1575

Saxton's map of Hampshire 1575

Extract from the Old Hampshire Mapped website about Saxton's map.

Map, hand coloured copper plate engraving, Southamtoniae, ie Hampshire, scale about 4 miles to 1 inch, engraved by Leonard Terwoort, Antwerp, Netherlands, published by Christopher Saxton, map maker, London? about 1575.

Published in the Atlas of England and Wales; it was usually issued in hand coloured form; measurements and notes made in the field were worked up later, with the help of earlier manuscript maps if available; Saxton almost certainly used the rudimentary triangulation techniques first described by the cartographer Frisius, Belgium, 1533.

Hills are drawn in profile to provide a general impression of the local topography, while named settlements are shown by a variety of symbols including a church with tower; rivers, coastline, some bridges, deer parks and woods are all included; the most obvious omission on Saxton's maps, to our eyes, are roads, which were not included on general county maps until the 1690s.

The map '... provides us with our first english example of accurate cartography': Colonel Close: 1930:: Hampshire Field Club.

Saxton's county maps were engraved by Ryther, Hogenberg, Reynolds, Terwoort and Scatter.

Direct link to Eling.(Settlement)

The ancient settlement of Eling circled in blue, to help locate it.

Zoomed in some more on the same map. Showing from the New Forest, Eling, Southampton, across to the Hamble.

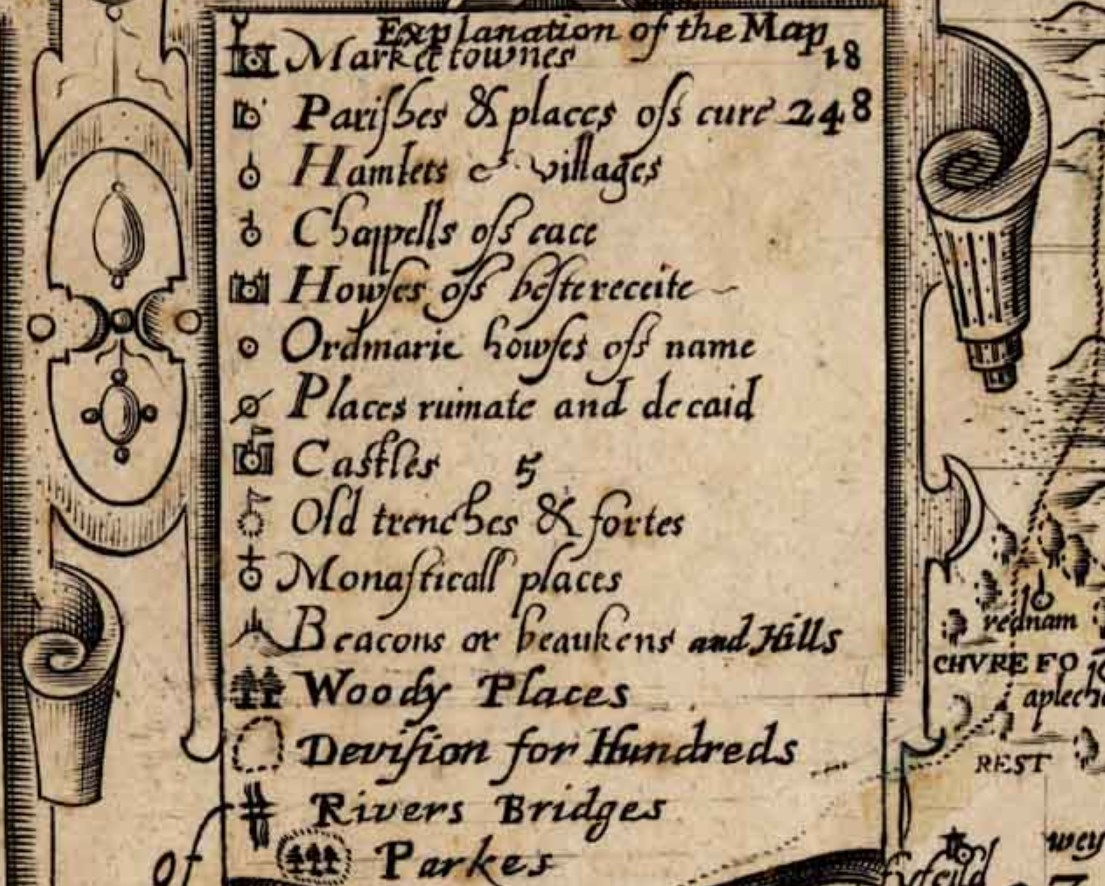

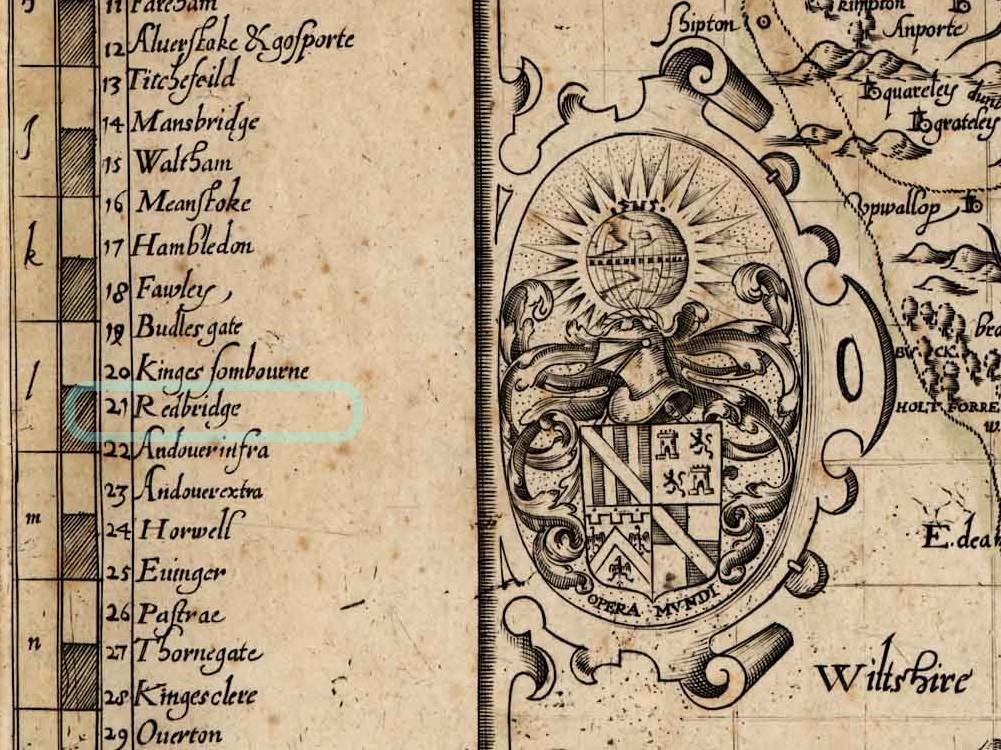

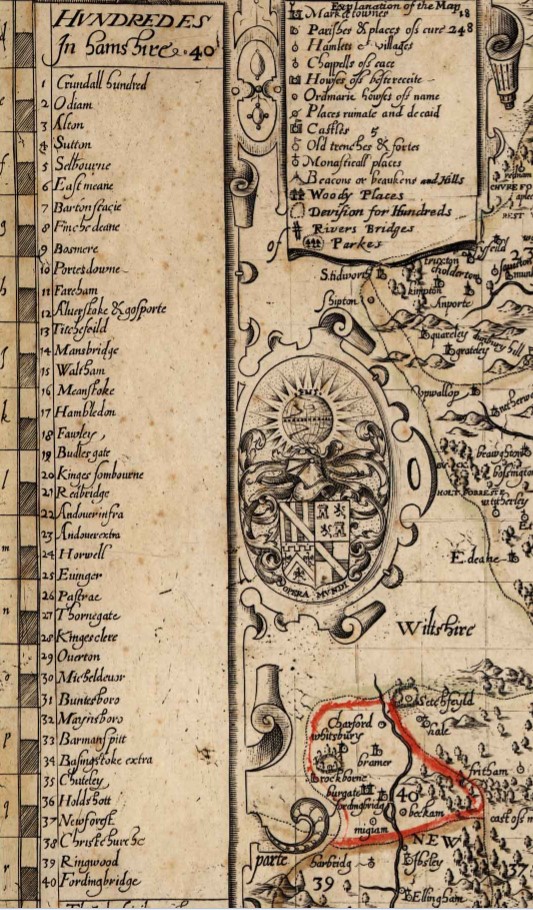

Norden 1595

Norden's Hampshire 1595

A map of Hampshire, including the Hundreds of the time. Remembering that a Hundred was an administrative area, part of and smaller than a County, and bigger than, and containing multiple Parishes.

The origin of the division of counties into hundreds is described by the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as "exceedingly obscure". It may once have referred to an area of 100 hides; in early Anglo-Saxon England a hide was the amount of land farmed by and required to support a peasant family, but by the eleventh century in many areas it supported four families. Alternatively the hundred may have been an area originally settled by one "hundred" men at arms, or the area liable to provide one "hundred" men under arms.

Either way, a huge area of land for such a small population.

![Norden s Hampshire 1595 Hundreds and key]() Details

Details

Eling is within the Hundred of Redbridge. Indicated on this map as 21. Fortunately, some of the hundreds have boundaries marked in red on this copy of the map, and 21 is one of them.

From this map it appears that the Hundred of Redbridge, at the time, extended North as far as Romsey, with its town and Abbey, including the Broadlands Estate, and South just past Elinge, on level with Lyndhurst. Note the spelling of Eling with an e at the end.

According to the Key or 'Explanation of the Map' the icon attributed to Elinge appears to be that of a Parish. This map is dated from 1595 and from elsewhere Parish Records commenced in 1537, which obviously predates the map.

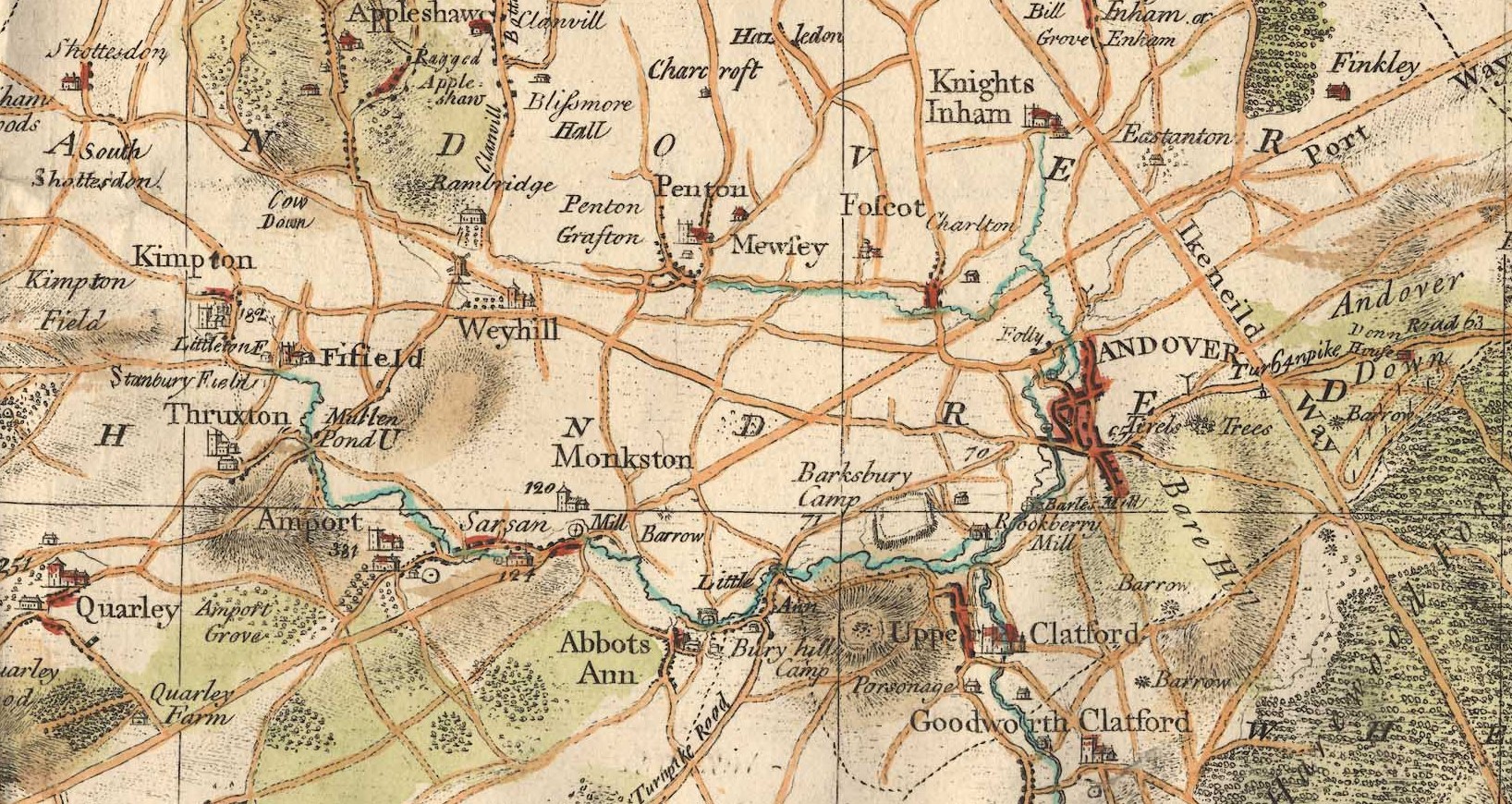

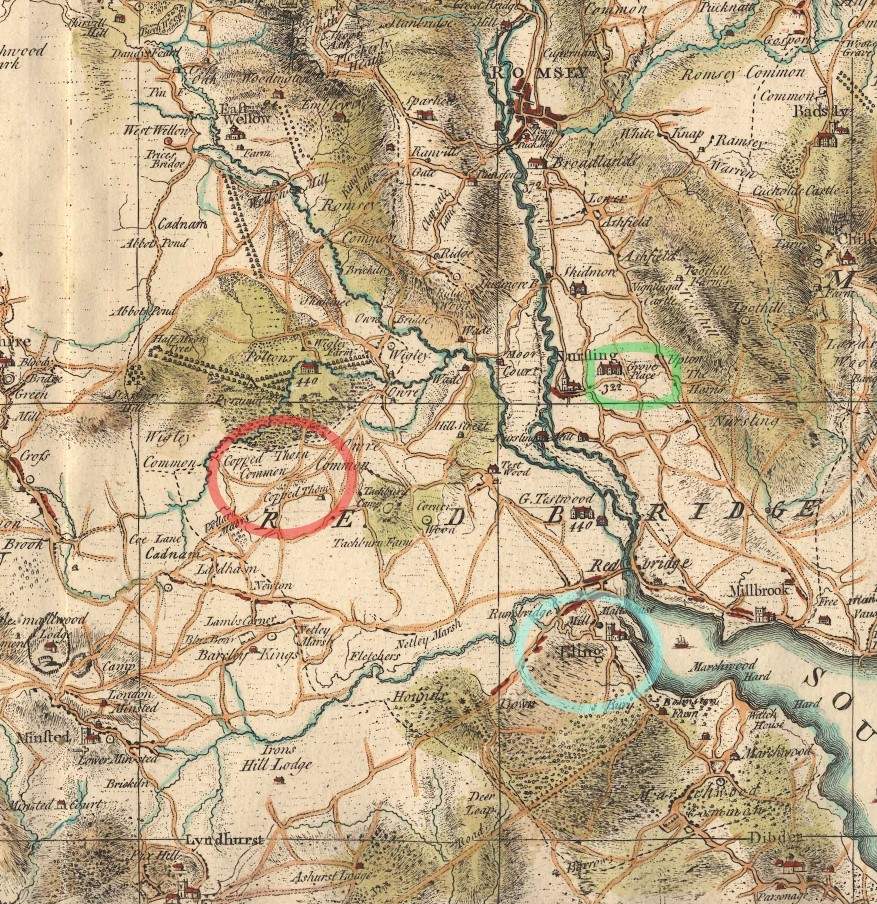

Taylor's Hampshire 1759

Taylor's Hampshire 1759 - Section 33.

Circled in green, Grove Place, in Nursling, is not part of this story, but does get a mention elsewhere on this site. Eling, the settlement, circled in blue, is the centre of attention. Eling the parish, takes up a large portion of the map, and the Hundred of Redbridge takes up even more. Extending to Romsey

Copped Thorn Common and Copped Thorn are circled in red, and turn up later in our story, under a slightly changed name.

I will have to look up house 440 at Poltons. It is interesting that Great Testwood carries the same number. Poltons is now known as Paultons Park - Home of Peppa Pig World. How things change.

The estate can be traced back to 1086 where the ‘Paulet’ manor was in the possession of Glastonbury Abbey. The house became derelict and burned down in a great fire on 5 November 1963. Click the link to read about the Estate's History.

The above only looks at Section 33 of Taylor's Map of Hampshire. If you want to look at the whole map, which is very decorated, follow the link to the article Taylor's Map of Hampshire 1759 which opens in a new window.

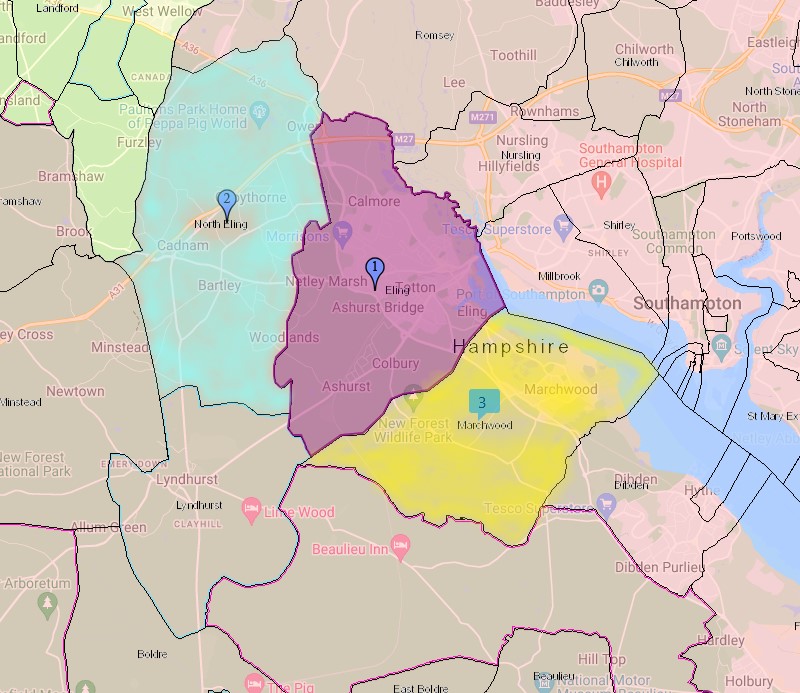

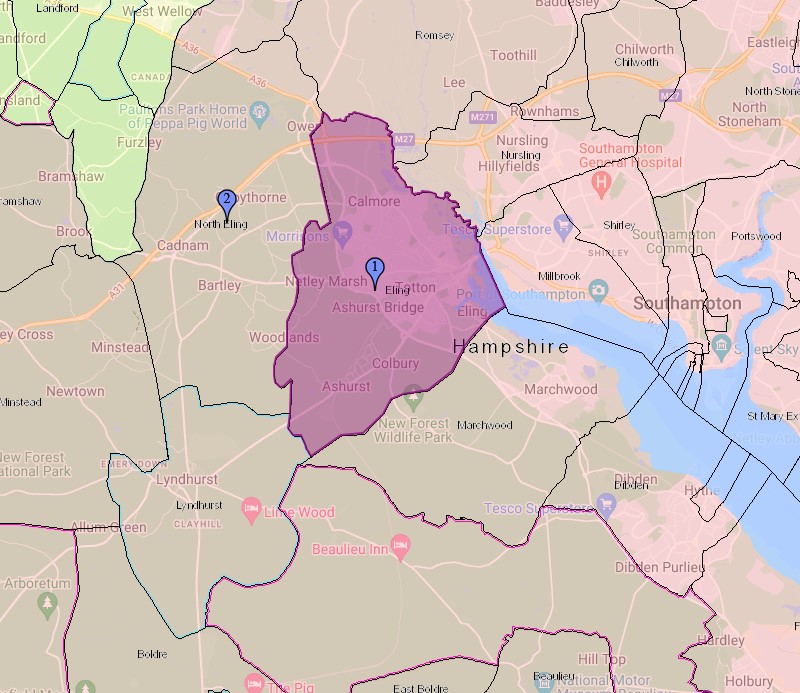

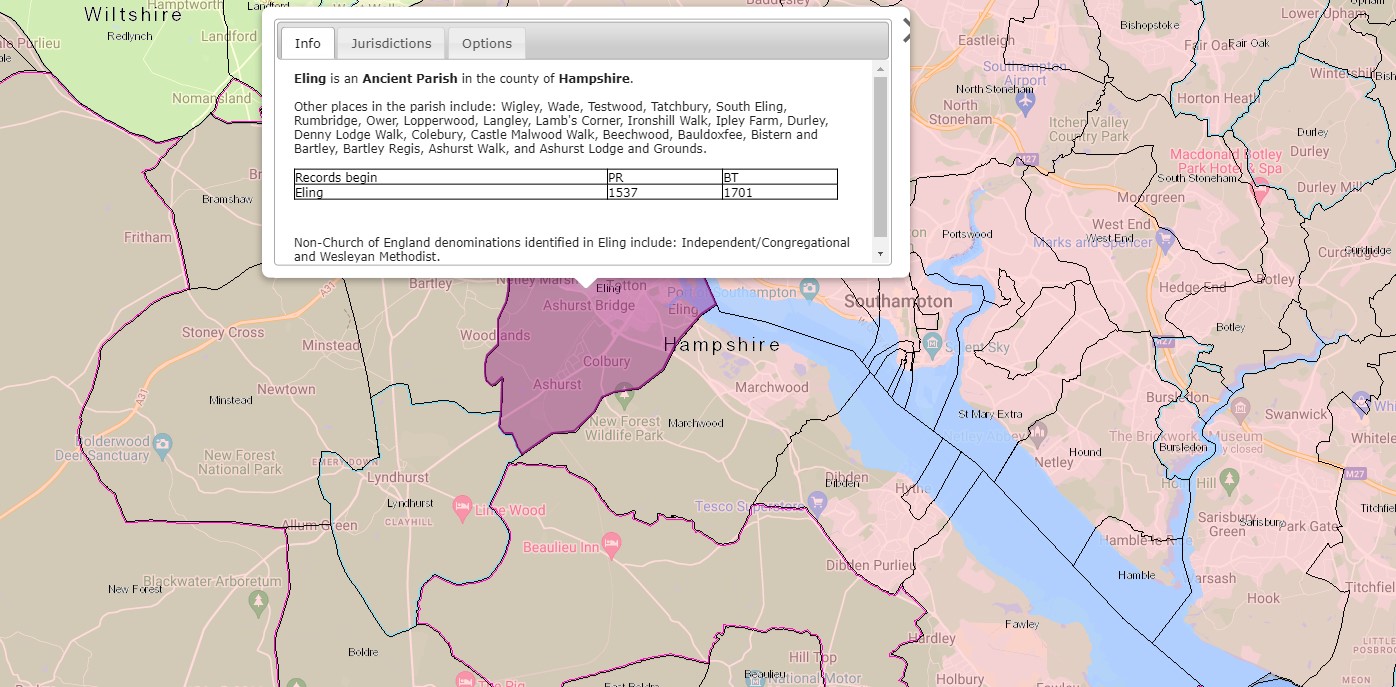

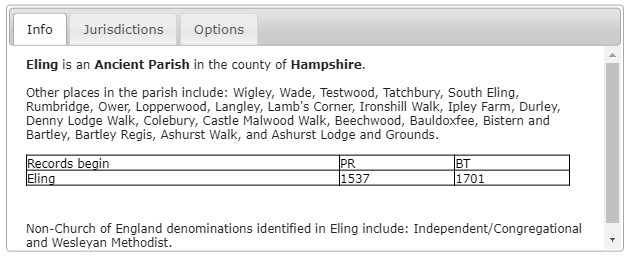

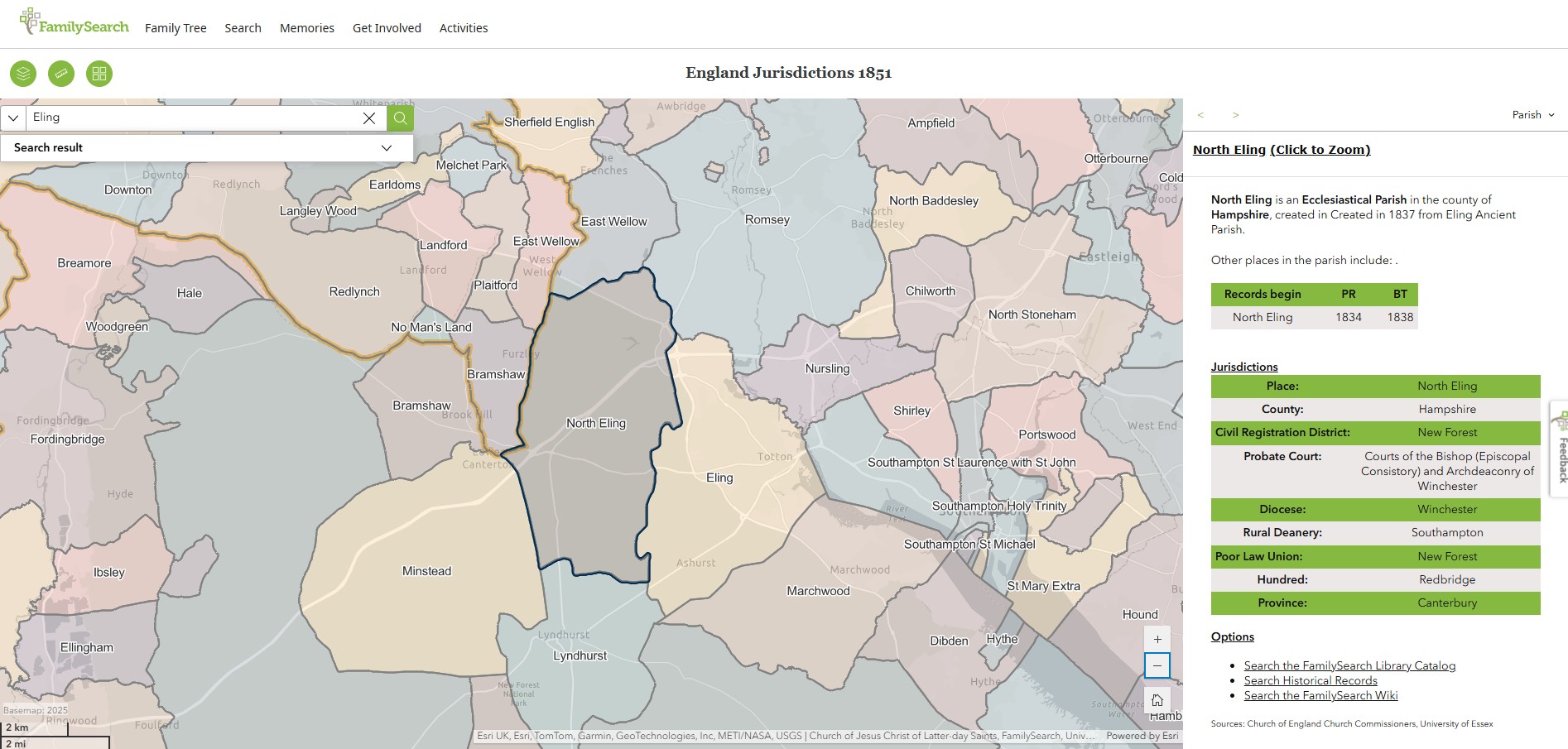

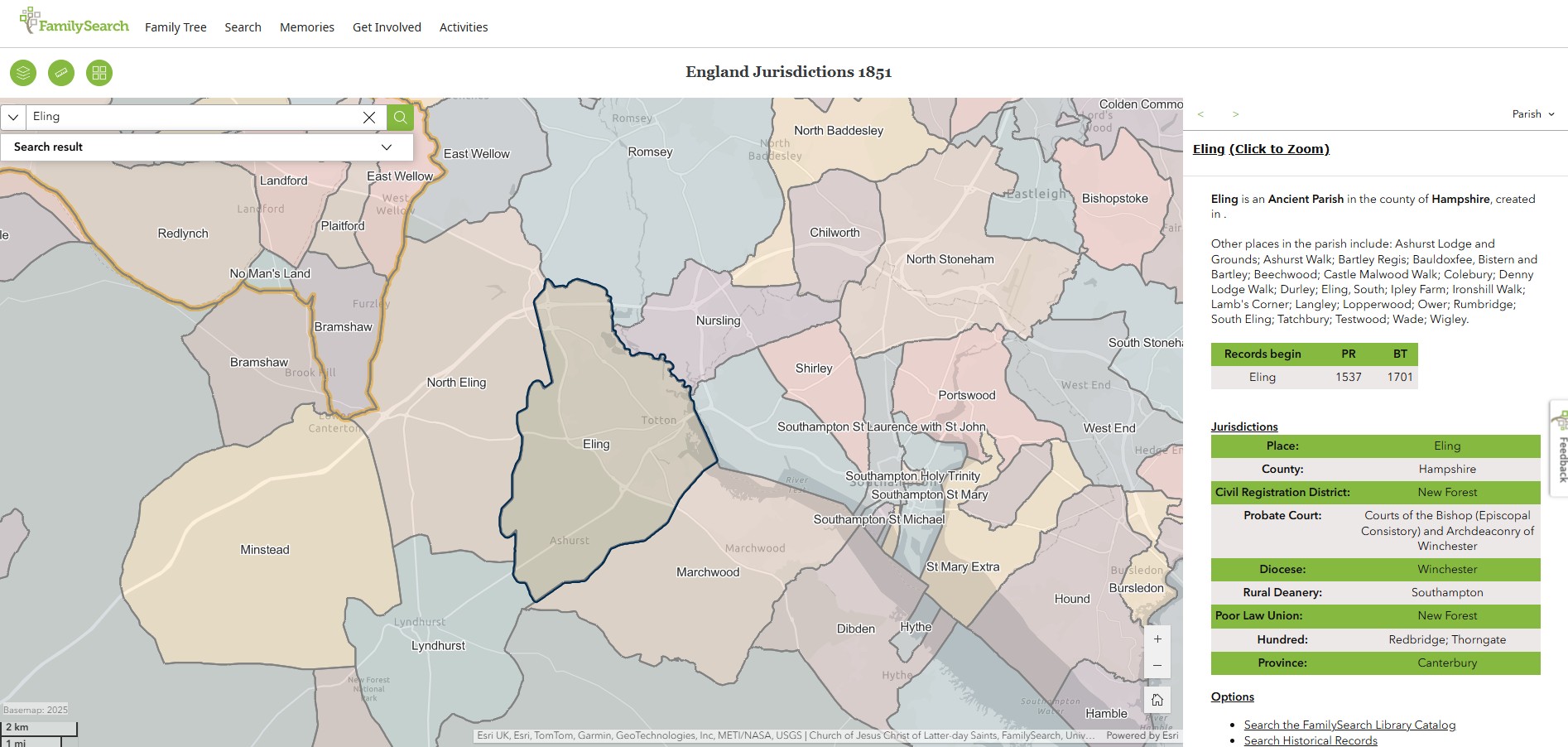

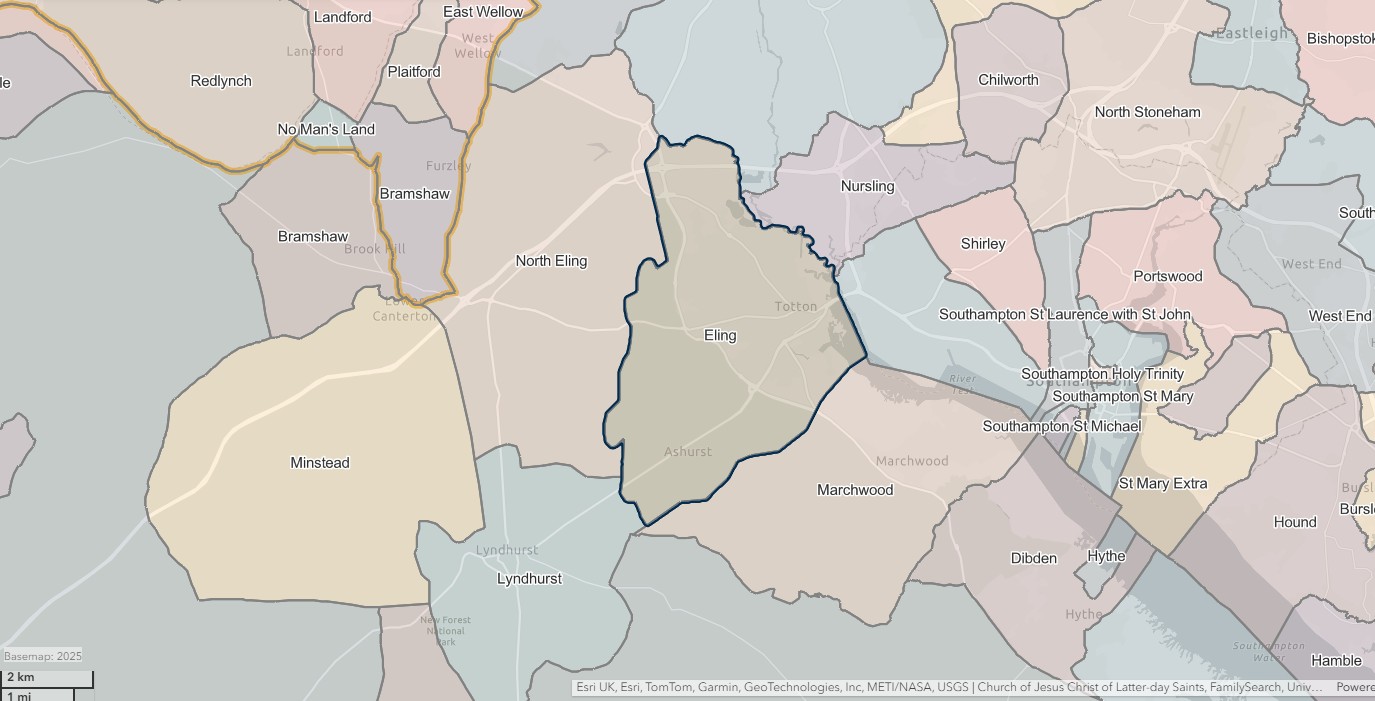

Eling Parish Split in three 1837-1846

Ancient Parish of Eling

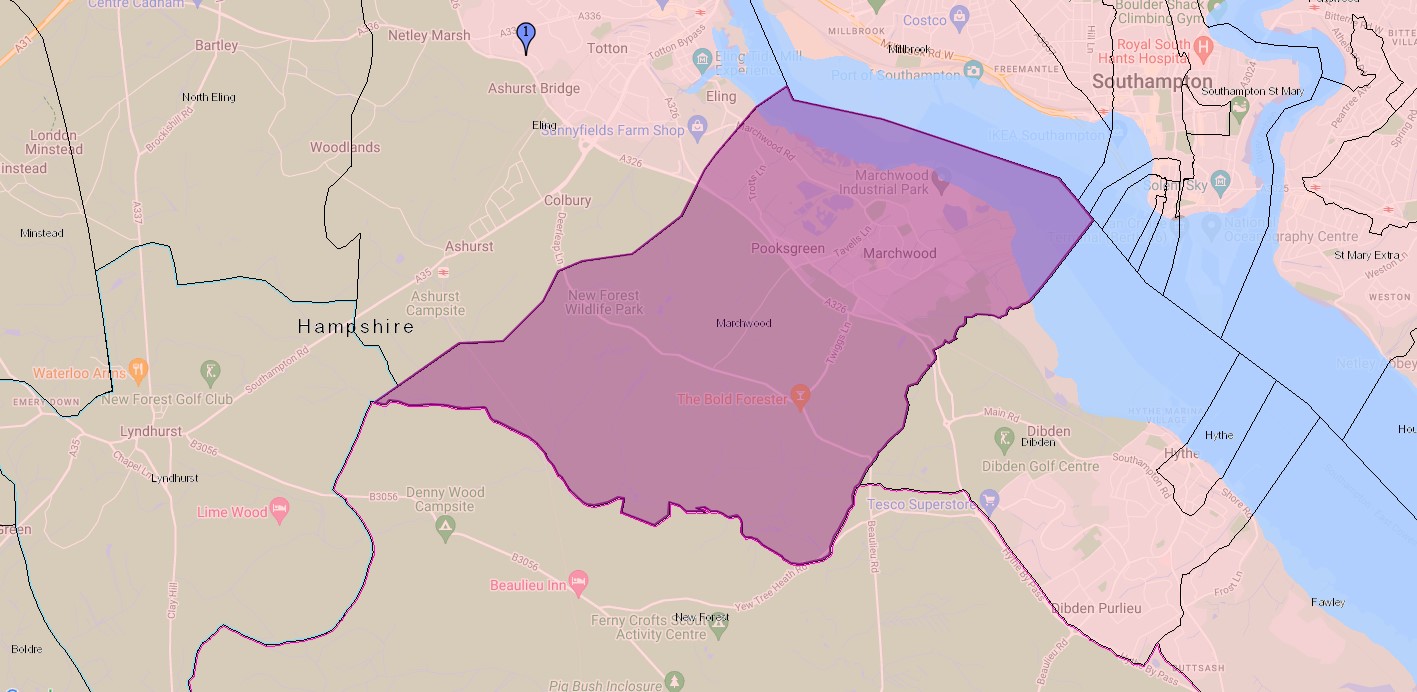

The Parish of Eling was divided, which is understandable, as it was a huge area, and would have had a growing population. Initially into, South to North, Marchwood, (1846), Ealing (Ancient) and North Eling (1837), .

The maps are from FamilySearch.

North Eling, blue wash, Eling, mouve, Marchwood, yellow.

Eling - re-sized

First the map with the revised size Eling parish as 1 and the newly formed North Eling as 2. Marchwood is also formed from the Ancient Parish of Ealing.

Eling is an Ancient Parish in the county of Hampshire

Other places include: Wigley, Wade, Testwood, Tatchbury, South Eling, Rumbridge, Ower, Lopperwood, Langley, Lamb's Corner, Ironshill Walk, Ipley Farm, Durley, Denny Lodge Walk, Colebury, Castle Malwood Walk, Beechwood, Bauldoxfee, Bistern and Bartley, Bartley Regis, Ashurst Walk, and Ashurst Lodge and Grounds.

Parish records begin in 1537 and Bishops Transcripts 1701.

Non-Church of England denominations identified in Eling include: Independent/Congregational and Wesleyan Methodist.

I have transcribed the image, which is clearly legible sat here, mainly to provide searchable text, but hopefully also to provide the information irrespective of the devise used to view this article.

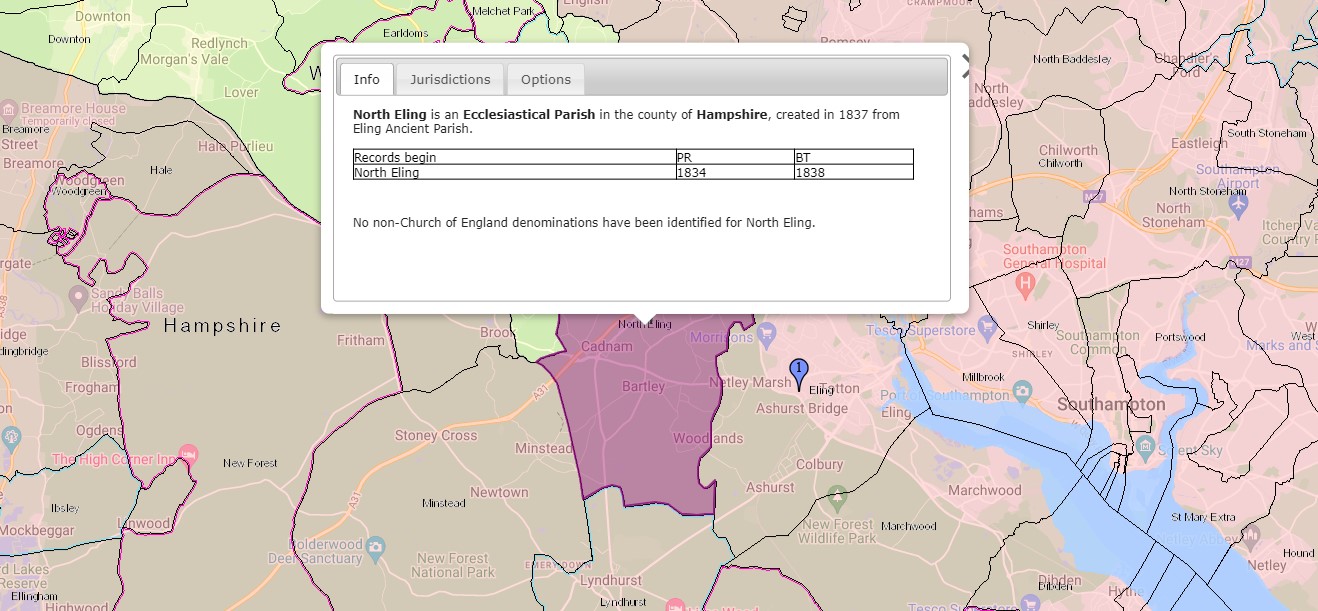

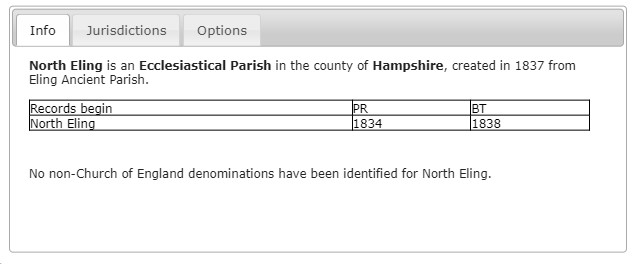

North Eling

North Eling is an Ecclesiastical Parish in the county of Hampshire, created in 1837 from Eling Ancient Parish.

Parish records begin in 1834 and Bishops Transcripts 1838. Interesting that the Parish records commence before the creation of the parish. No non-Church of England denominations have been identified for North Eling.

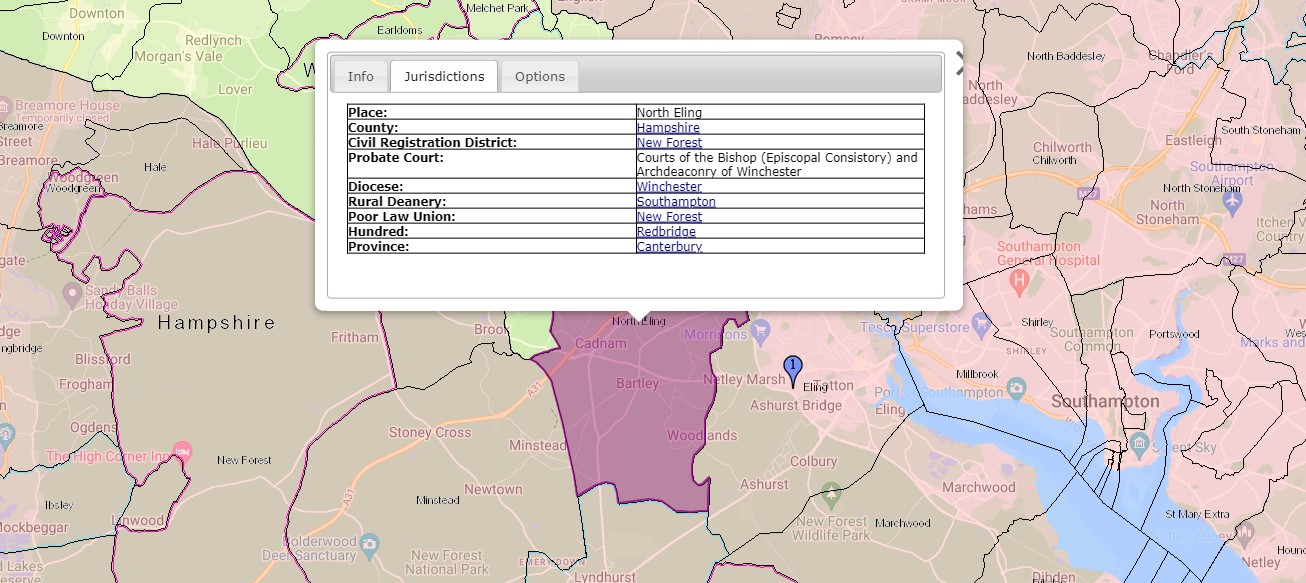

Jurisdictions;

- Place; North Eling

- County; Hampshire

- Civil Registration District; New Forest

- Probate Court; Courts of the Bishop (Episcopal Consistory) and Archdeaconry of Winchester.

- Diocese; Winchester

- Rural Deanery; Southampton

- Poor Law Union; New Forest

- Hundred; Redbridge

- Province; Canterbury

All the Jurisdictions apart from the place are the same for all three parishes.

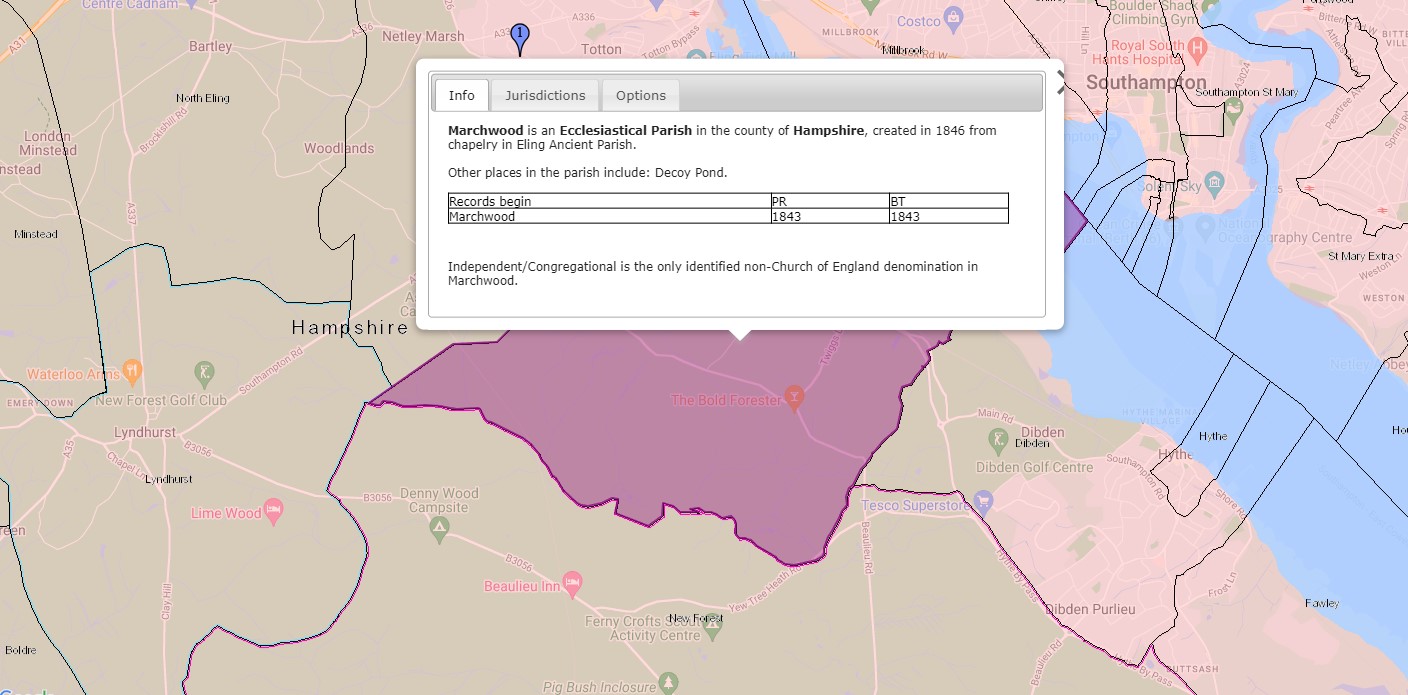

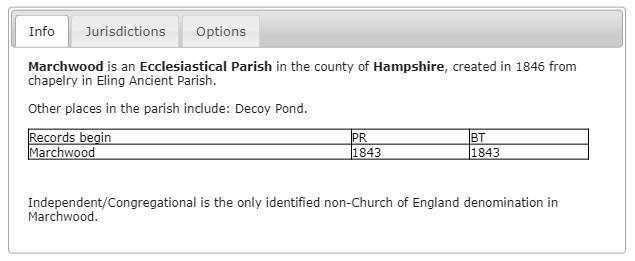

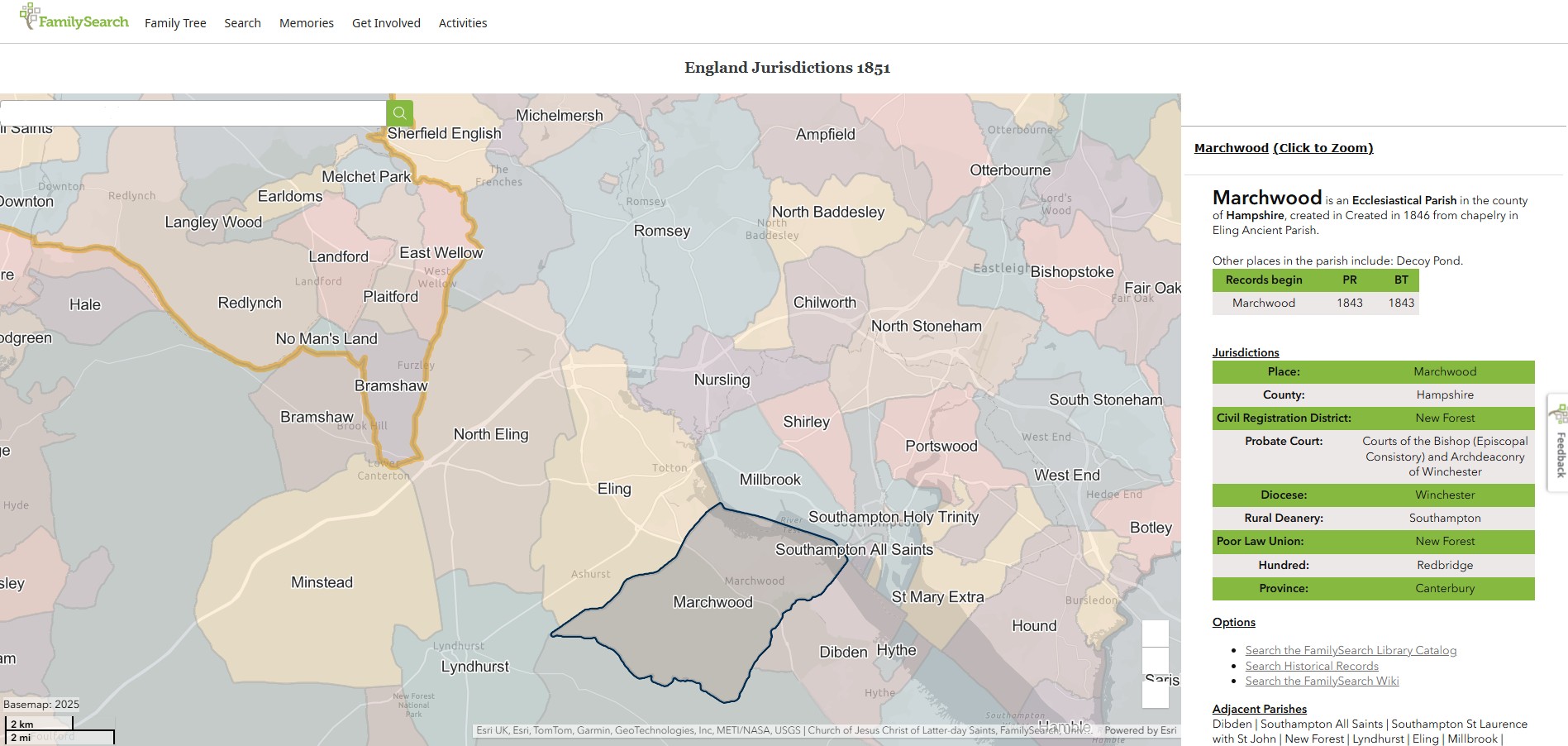

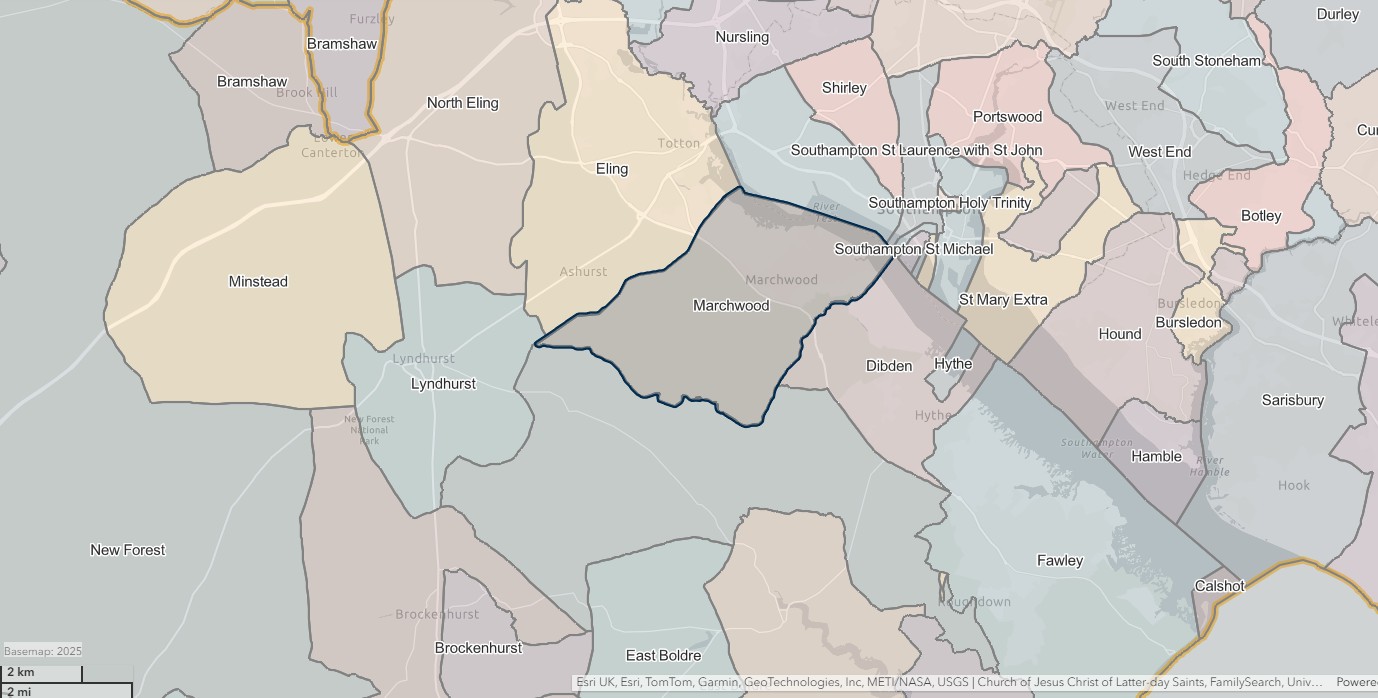

Marchwood

Nine years after the division of the Ancient Parish of Eling to create North Eling, a further split to create the Parish of Marchwood.

Marchwood is an Ecclesiastical Parish in the county of Hampshire, created in 1846 from chapelry in Ealing Ancient Parish.

Other places in the parish include: Decoy Pond.

Parish records begin in 1843 and Bishops Transcripts 1843. Interesting that the Parish records commence before the creation of the parish.

Independent/Congregational is the only identified non-Church of England denomination in Marchwood.

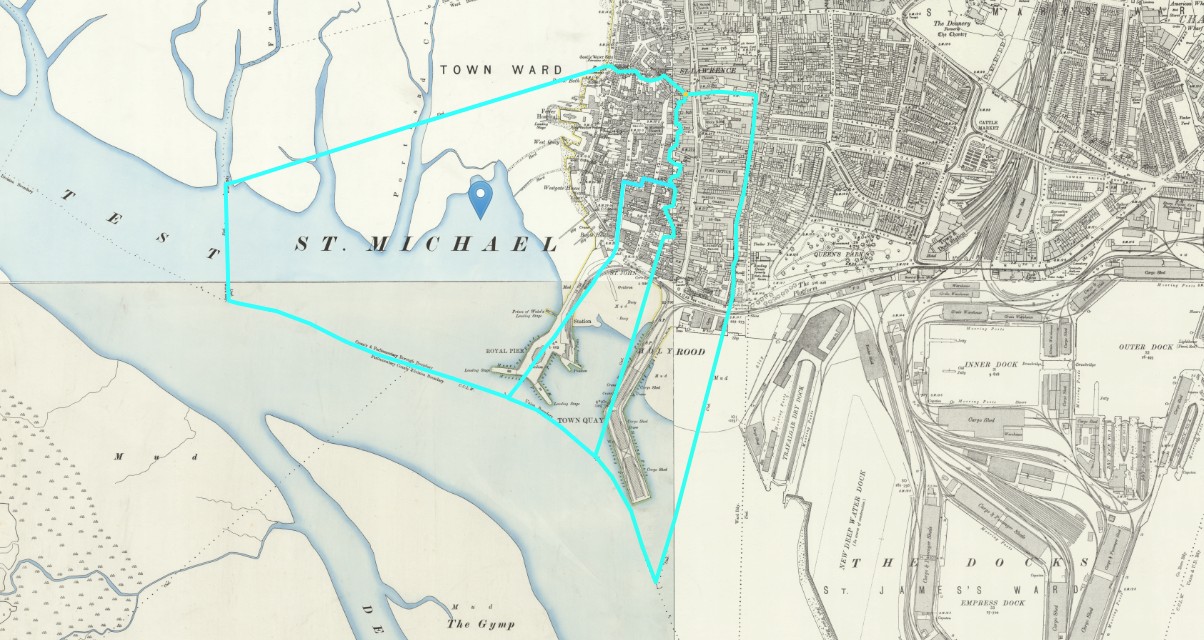

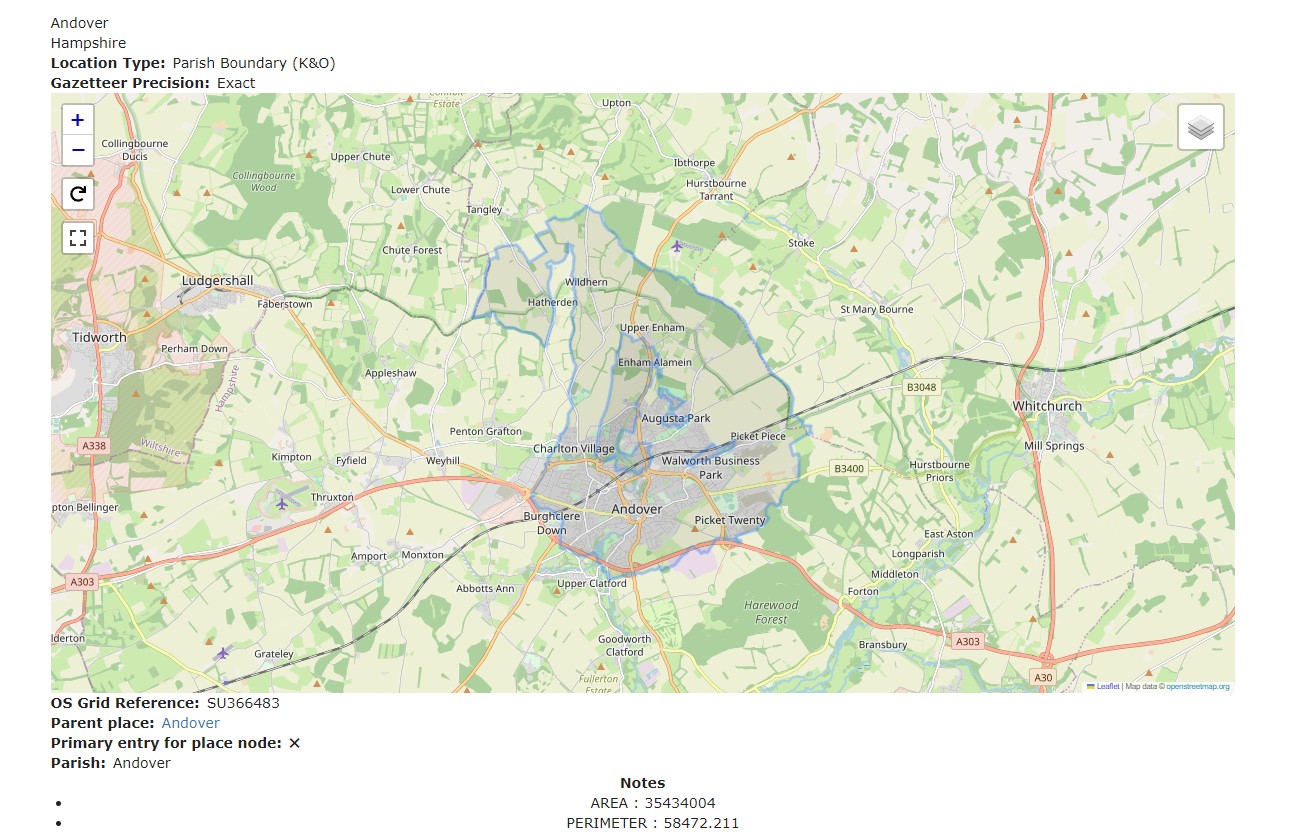

ArcGIS Church of England Parishes Map

An extract of ArcGIS Church of England Parishes Map focused on the parish of Eling

Ordnance Survey

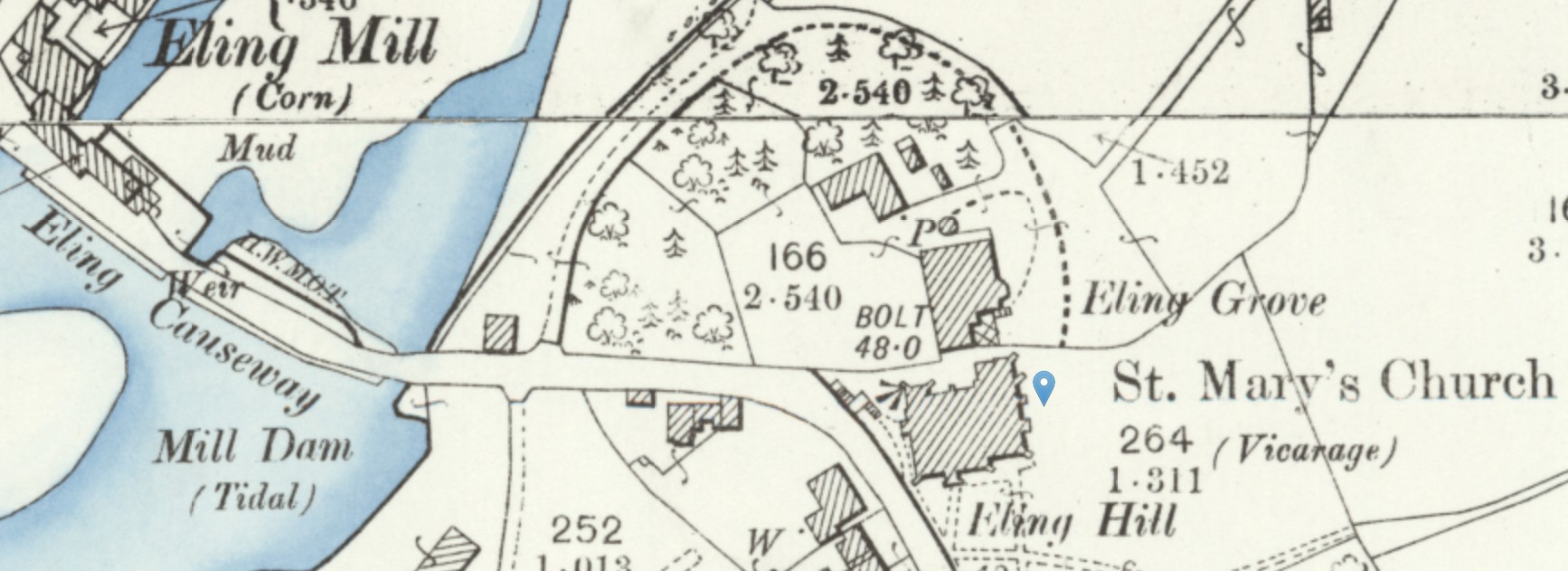

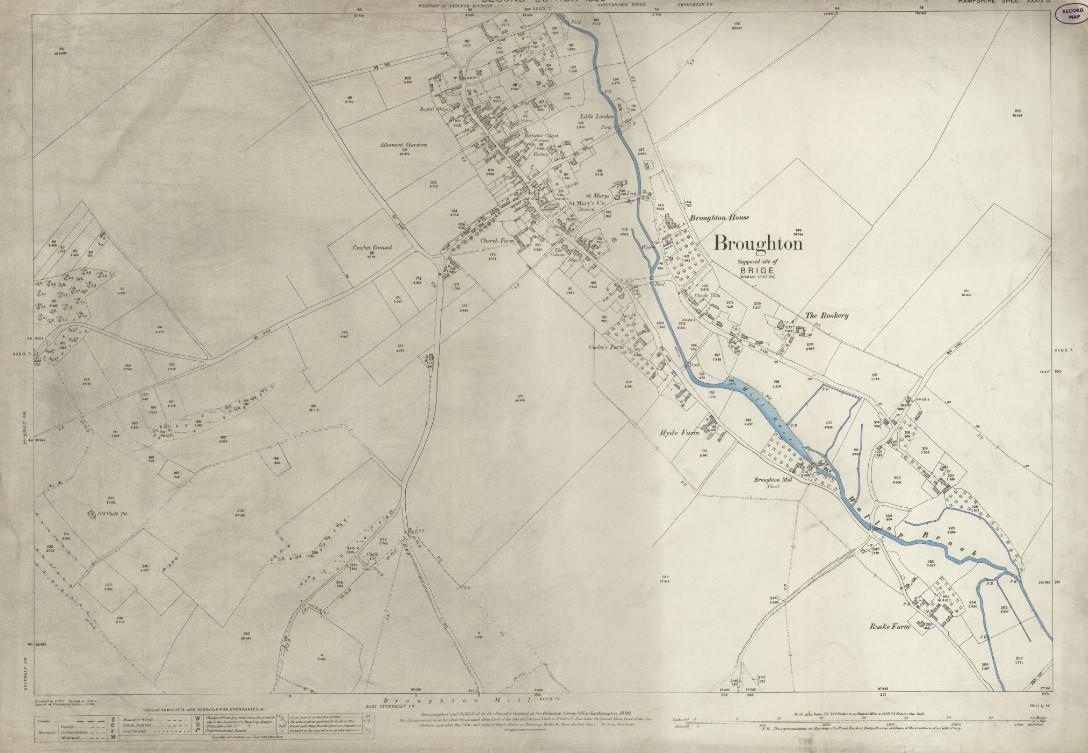

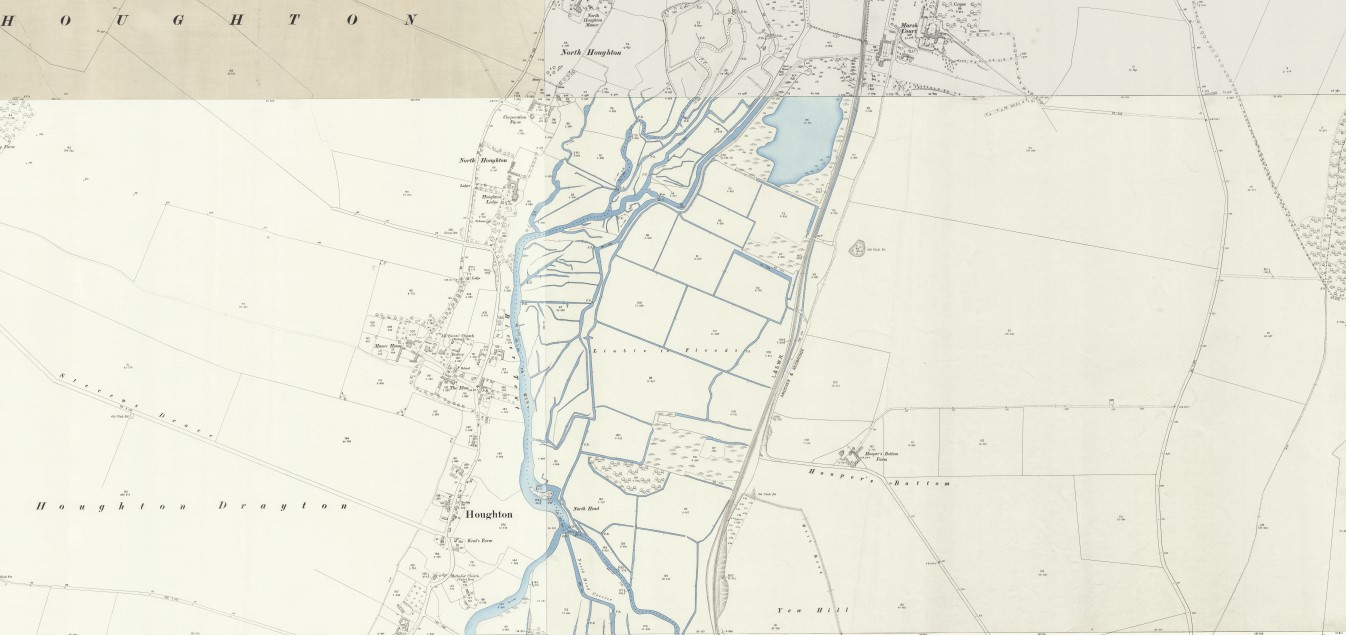

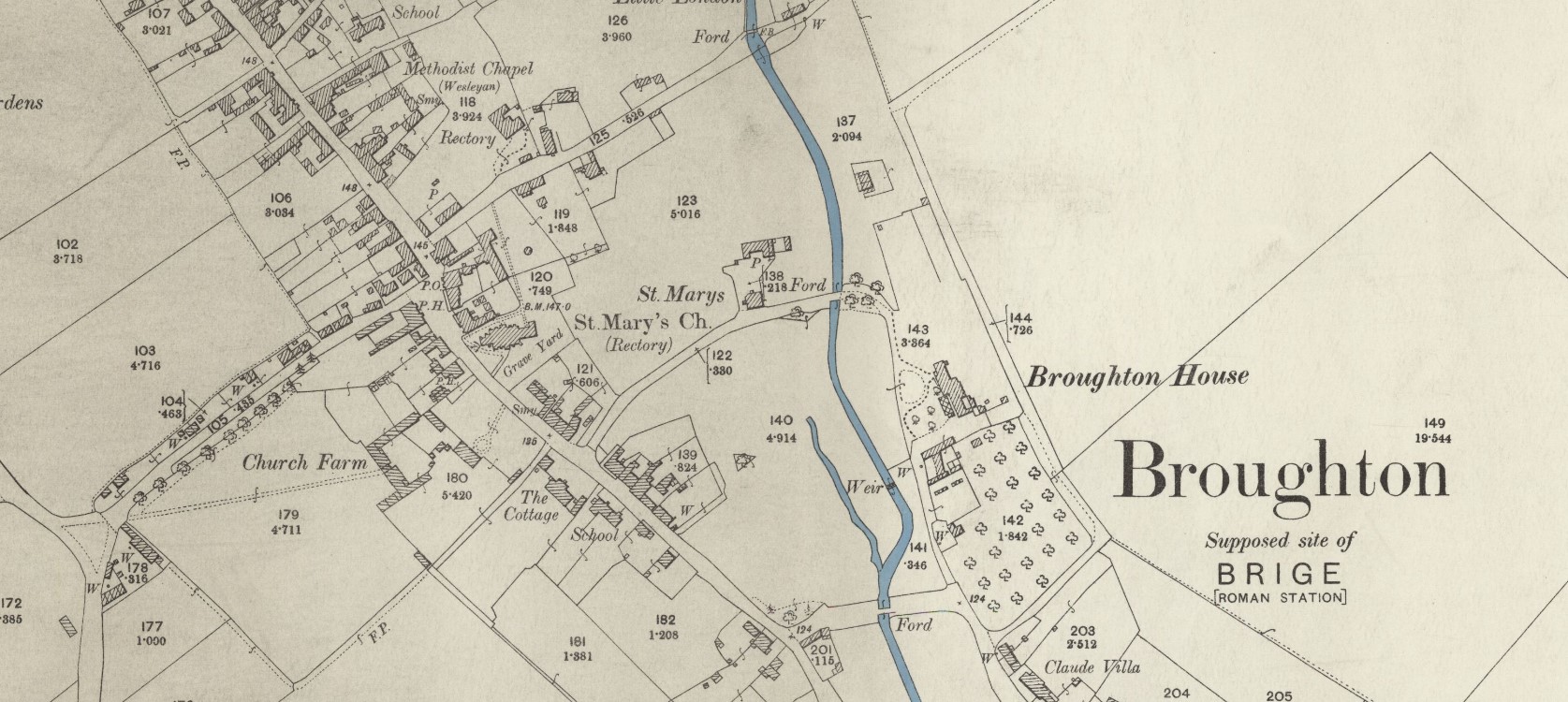

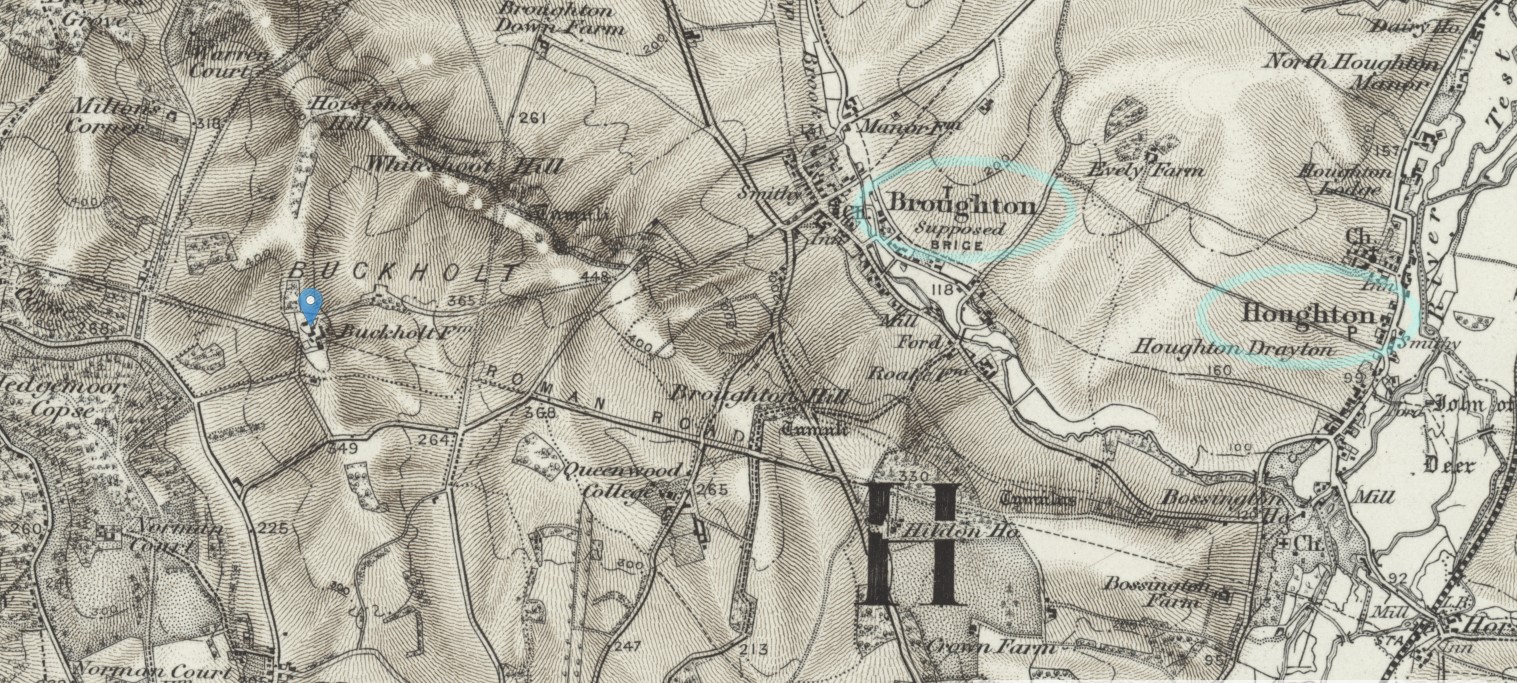

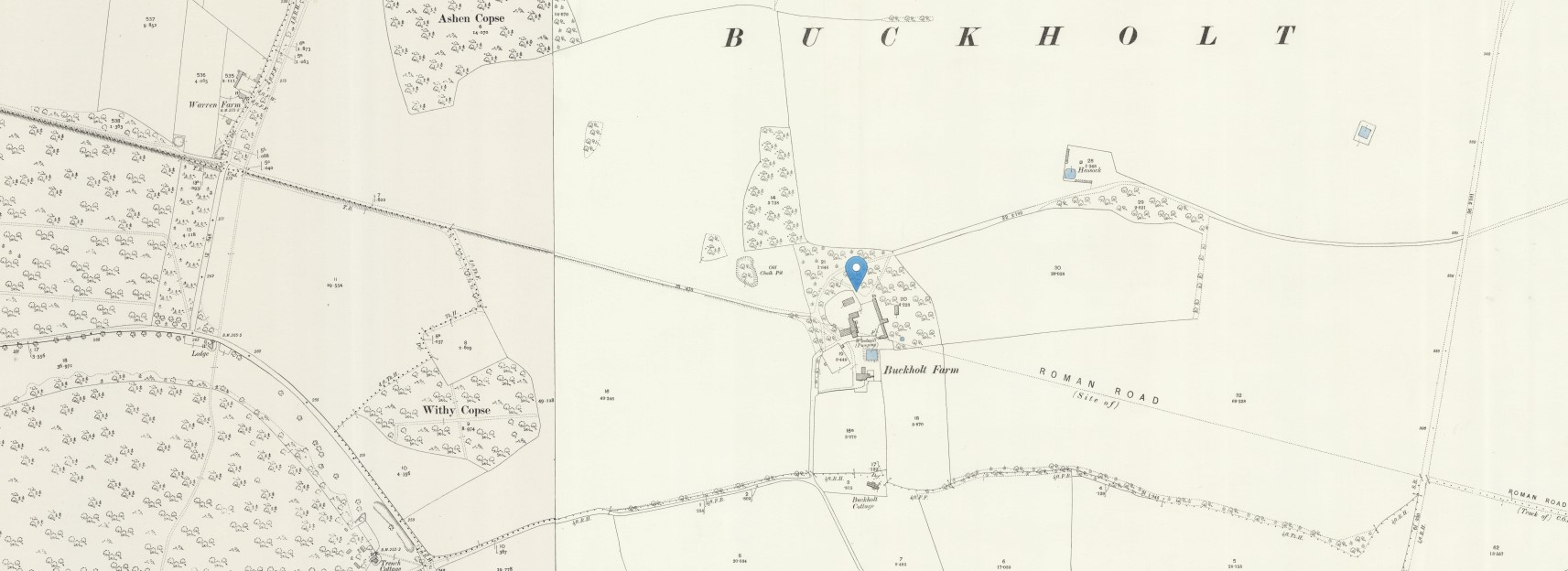

OS 25 Old Map Eling village - Hampshire and Isle of Wight LXIV.12 Revised: 1895, Published: 1897

OS 25 Old Map Eling village - Hampshire and Isle of Wight LXIV.12 Revised: 1895, Published: 1897

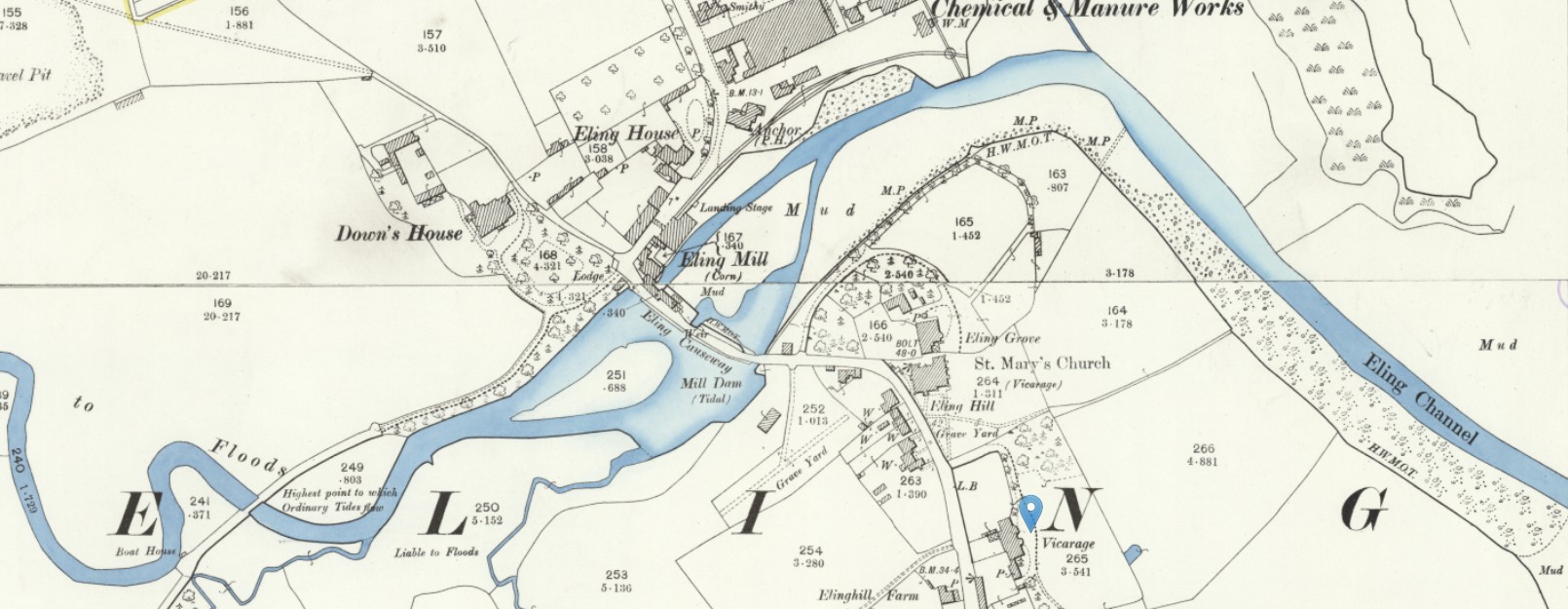

OS 25 Old Map Eling and Totton - Hampshire and Isle of Wight LXIV.8 Revised: 1896, Published: 1897

OS 25 Old Map Eling and Totton - Hampshire and Isle of Wight LXIV.8 Revised: 1896, Published: 1897

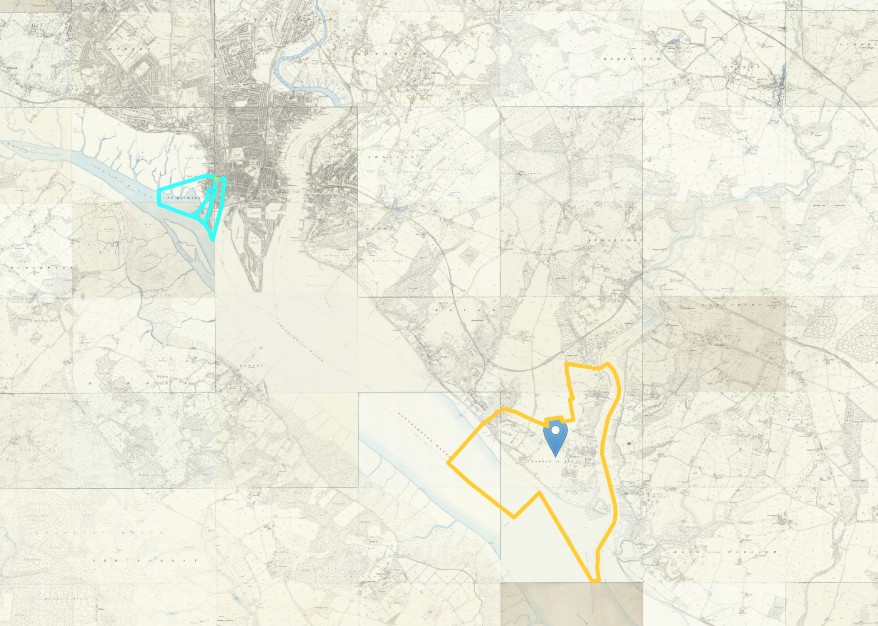

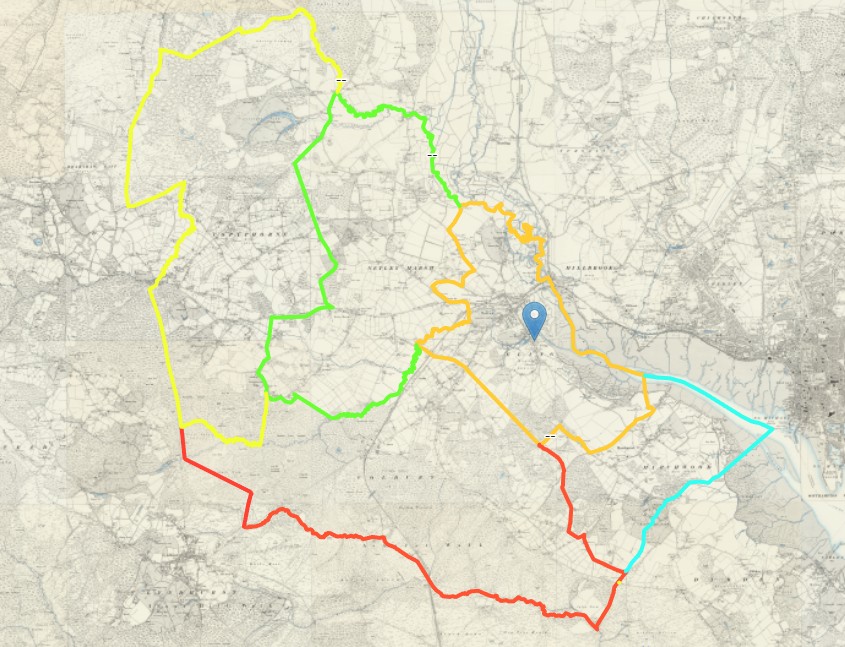

OS 6 Old Map Ancient Eling 4 parish boundaries plus Eling mark - Hampshire & Isle of Wight Sheet LXIV.NE Revised: 1895 to 1896, Published: 1897

OS 6 Old Map Ancient Eling 4 parish boundaries plus Eling mark - Hampshire & Isle of Wight Sheet LXIV.NE Revised: 1895 to 1896, Published: 1897

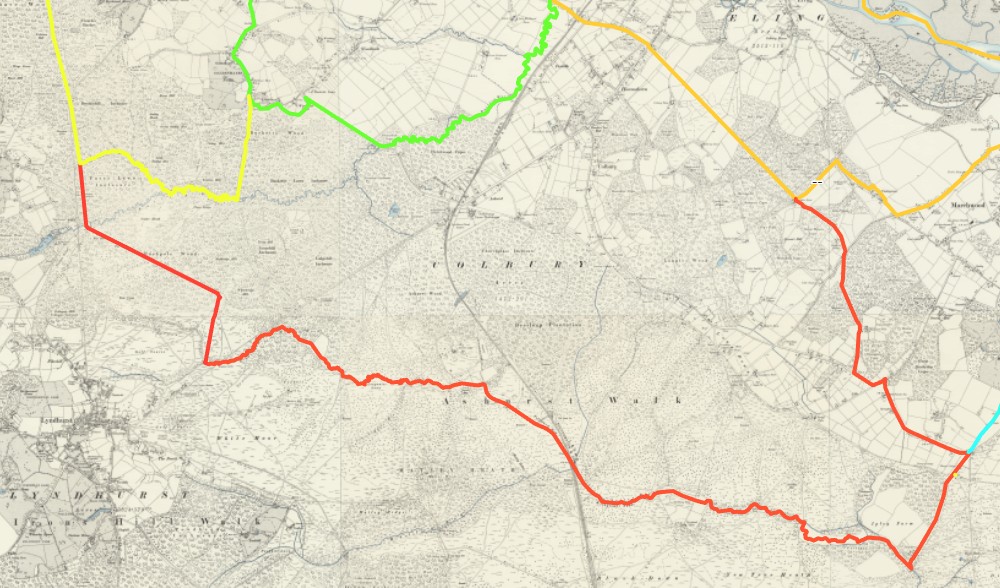

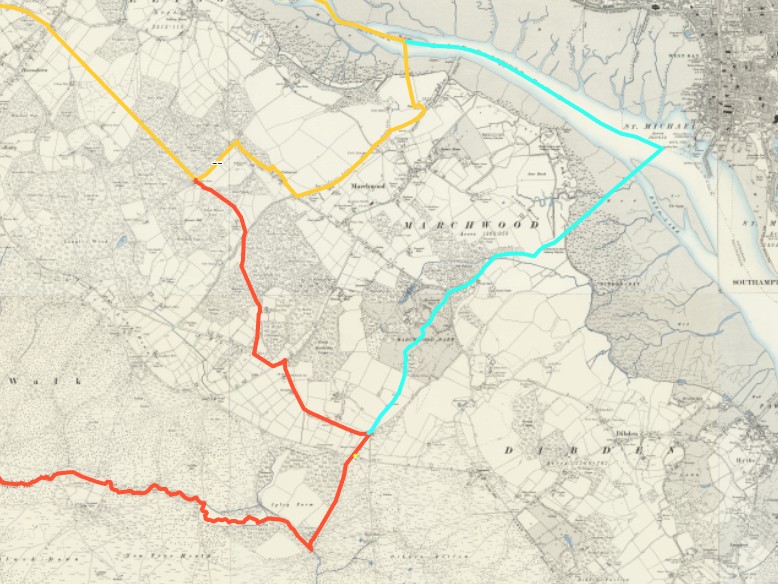

For this rendition of the 6" version of the same Ordnance Survey Map I have slowly traced the boundary makers shown on the map to more easily see the ancient parish of Eling, as well as the now four resultant parishes.

First it was one parish, then three, then four at the time of this map, 1895.

It is made up of several map sheets, one of which is Hampshire & Isle of Wight Sheet LXIV.SE

Revised: 1895, Published: 1898.

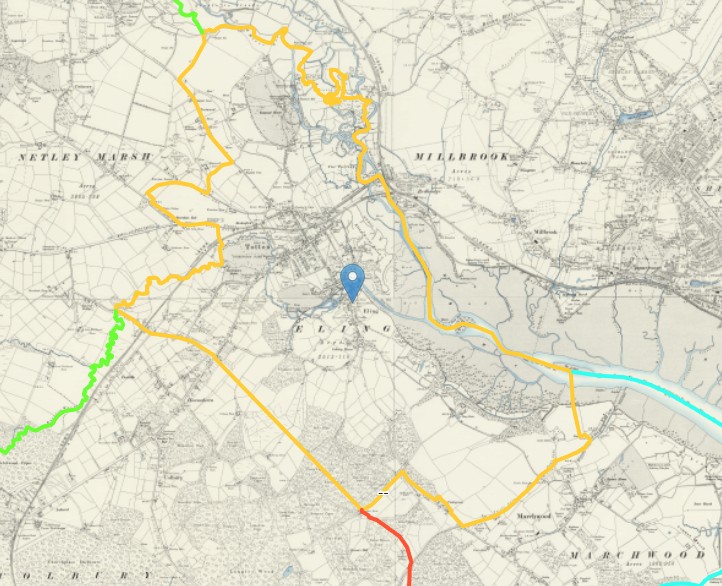

The village of Eling is shown by the blue marker.

The 1895 Eling Parish boundary is shown with the orange line.

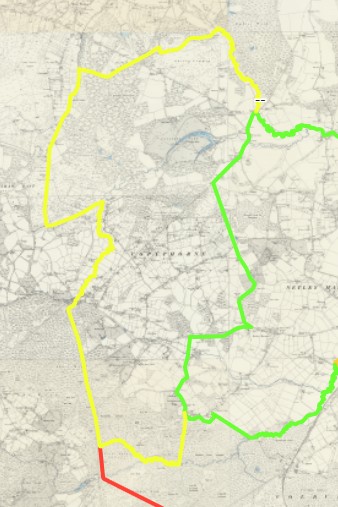

The Parish of Copythorne has a yellow outer boundary.

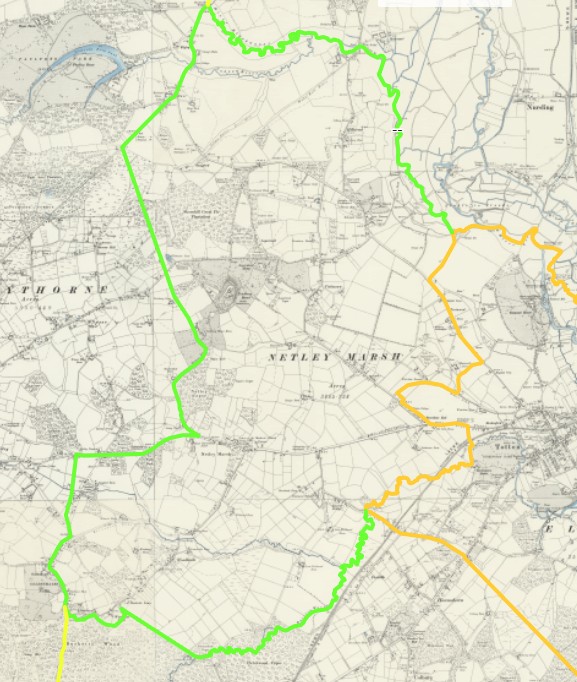

The Parish of Netley Marsh has a green outer boundary.

The Parish of Colbury has a red outer boundary.

The Parish of Marchwood has a light blue outer boundary.

With inner boundaries sharing adjacent parishes colours.

I have saved the lines, but unfortunately they will not show when you follow the link, click the map, to the source information.

The following maps are zoomed in to each parish.

The 1895 Eling Parish boundary is shown with the orange line.

The 1895 Parish of Copythorne has a yellow outer boundary.

The 1895 Parish of Netley Marsh has a green outer boundary.

The 1895 Parish of Colbury has a red outer boundary.

The 1895 Parish of Marchwood has a light blue outer boundary.

Before 1066

Prehistoric

Prehistoric Hampshire

Prehistoric evidence in Hampshire

Prehistoric evidence in Hampshire - Atlas of Hampshire's Archaeology

Extracted from Atlas of Hampshire Archaeology, well worth the read in it's entirety.

The Atlas of Hampshire's Archaeology

The Historic Environment Record (HER) contains around 50,000 entries that describe the known archaeology of Hampshire. Analysing the distributions of this complex data by using GIS allows fascinating insights into the evolution of the Hampshire landscape. The Atlas of Hampshire's Archaeology presents HER data in a graphic and understandable way and provides the opportunity to enjoy and understand the archaeological story of Hampshire. Displaying the HER data alongside other information, such as topography, rivers, geology and landscape allows new insights and the patterns of data to be readily appreciated. The Atlas of Hampshire's Archaeology was developed to support an understanding of the archaeological potential of different landscapes. The maps are equally interesting to a wider audience including those seeking to know what has been found in their area, students and academics undertaking research, and consultants preparing advice for developers. The following pages offer an opportunity to share the emerging story of Hampshire.

This forms a significant part of this section, hence leading with it. The Maps and text are in the various periods without continuously repeating the above introduction.

Prehistoric evidence in Hampshire - Paleolithic

Paleolithic, aka Old Stone Age - c. 3.3 million – c. 11,700 years ago.

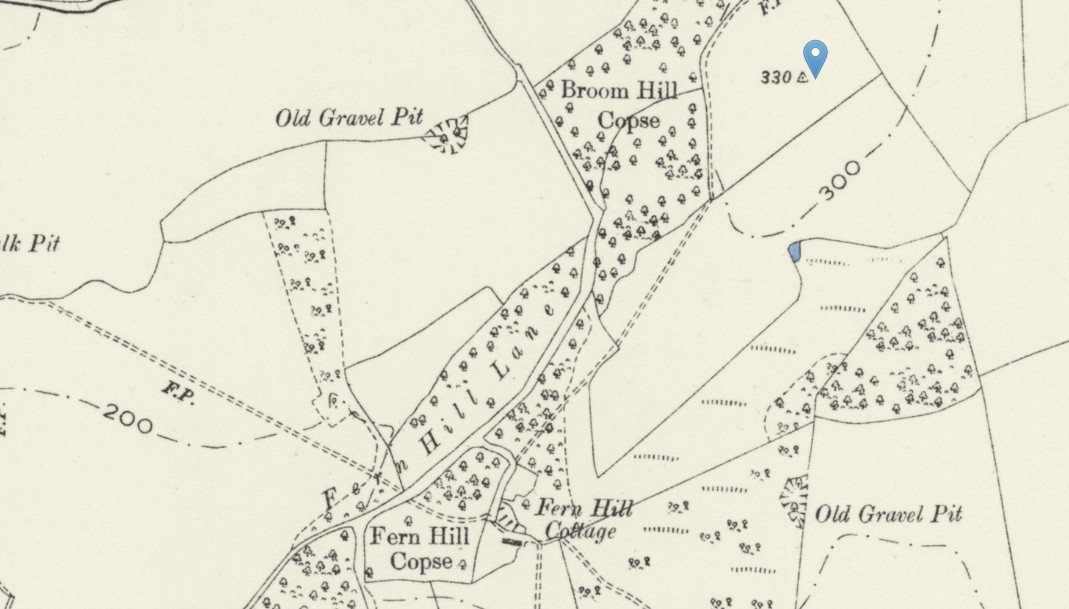

Paleolithic - Broom Hill, Braishfield

Although the ecclesiastical parish of Braishfield was only formed in 1855 and the civil parish just under a century later there is evidence of human activity in the area in the Paleolithic era, about 500,000 years ago. At Broom Hill is probably the oldest building in Britain – an 8,500 year old mesolithic hut discovered by Michael O’Malley in 1971 (for further information click on links Hampshire Archaeology). There is evidence of intermittent settlement from the late Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman and late Saxon periods. The site is particularly noted for the range and quality of Mesolithic flint tools, and it would have been visited seasonally by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. In later periods of settled agricultural activity, from the Neolithic period onwards, the site would have been inhabited for longer periods.

The Romans settled at Fernhill not far from the Mesolithic site. A late third century bath house was excavated in 1976, part of a much older villa complex consisting of at least six substantial buildings which were occupied long before the construction of the bath house. North of Fernhill Farm a trial trench showed chalk blocks laid in mortar, and finds included bricks and roofing tiles. Excavations by Test Valley Archaeological Committee in 1976 revealed a bath house block and C.4 Roman coins

Little is recorded of Braishfield until 1043 when, as part of the manor of Michelmersh, the lands were donated by Queen Emma to the cathedral clergy at Winchester. Later much of this holding was released to secular landowners, including two Oxford colleges, one of which owned land in the village up to the Second World War.

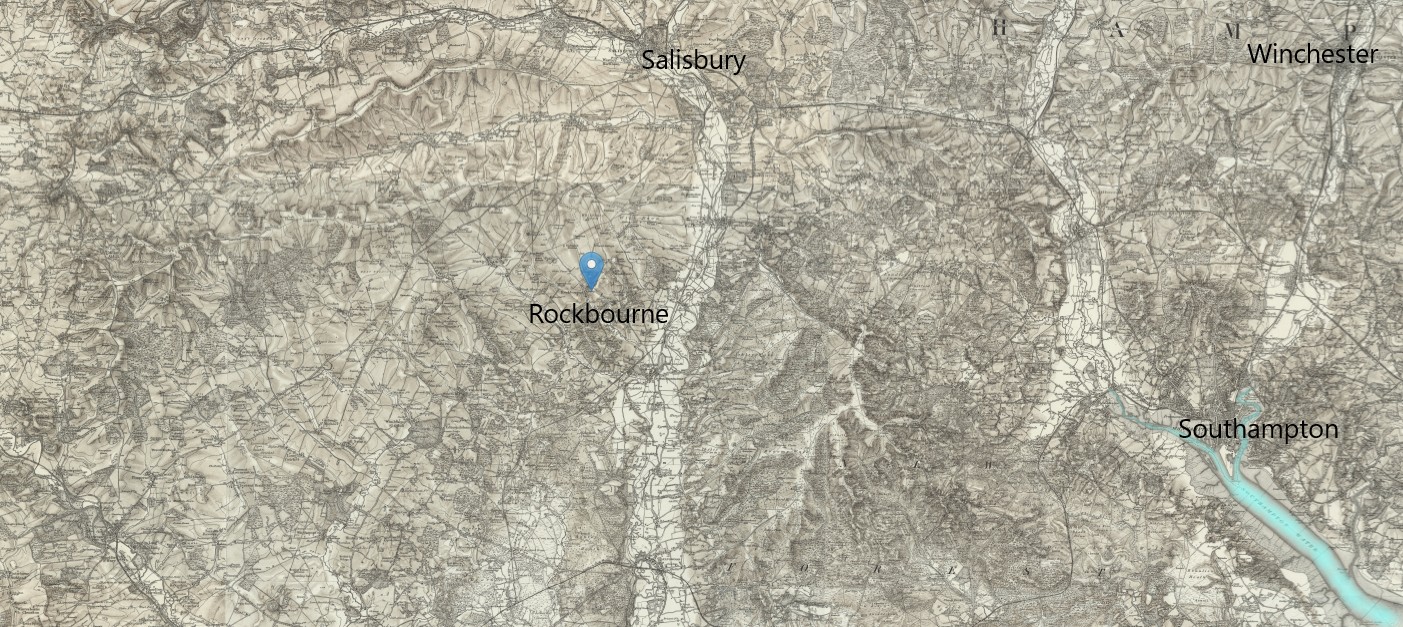

OS 25 Old Map Broom Hill Hampshire - Hampshire & Isle of Wight Sheet XLIX.NW Revised: 1894 to 1895, Published: 1897

OS 25 Old Map Broom Hill Hampshire - Hampshire & Isle of Wight Sheet XLIX.NW Revised: 1894 to 1895, Published: 1897

Currently, an assumption that Broom Hill is the hill, summit 330 ft, adjacent to Broom Hill Copse.

Open Street Map has the same position annotated as Broom Hill with an elevation of 106m, 348 ft.

The same map but zoomed out to show Braishfield as well as Broom Hill Copse.

Another article of interest, Buried in time, Broom Hill, Braishfield. How the Broom Hill site was found by an Ordnance Survey, surveyor, and the subsequent excavation and finds.

Radiocarbon dates suggest that it was in use for about two thousand years from 6500 to 4500 BC, making it a Later Mesolithic site.

Prehistoric evidence in Hampshire - Mesolithic

The Hunter Gatherers

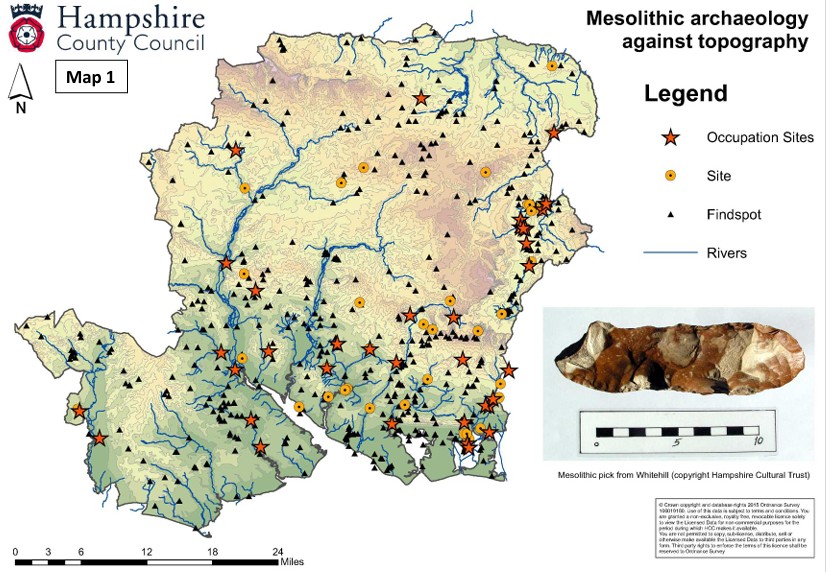

Prehistoric evidence in Hampshire - Atlas of Hampshire's Archaeology - Mesolithic

Mesolithic Hampshire 10,000 BC to 4,000 BC

The Mesolithic is characterised by small groups of nomadic hunter gatherers, who moved through the landscape hunting, fishing and gathering wild foods. They would have known their environment and the resources within it intimately and would have moved with the seasons, knowing where to find animals or following the migrating animals, and knowing where different foods were available throughout the year. This way of life leaves little trace in the archaeological record. The Mesolithic sites are frequently identified through the distinctive stone tools, which are generally small, and the small camps and occupation sites that these are associated with.

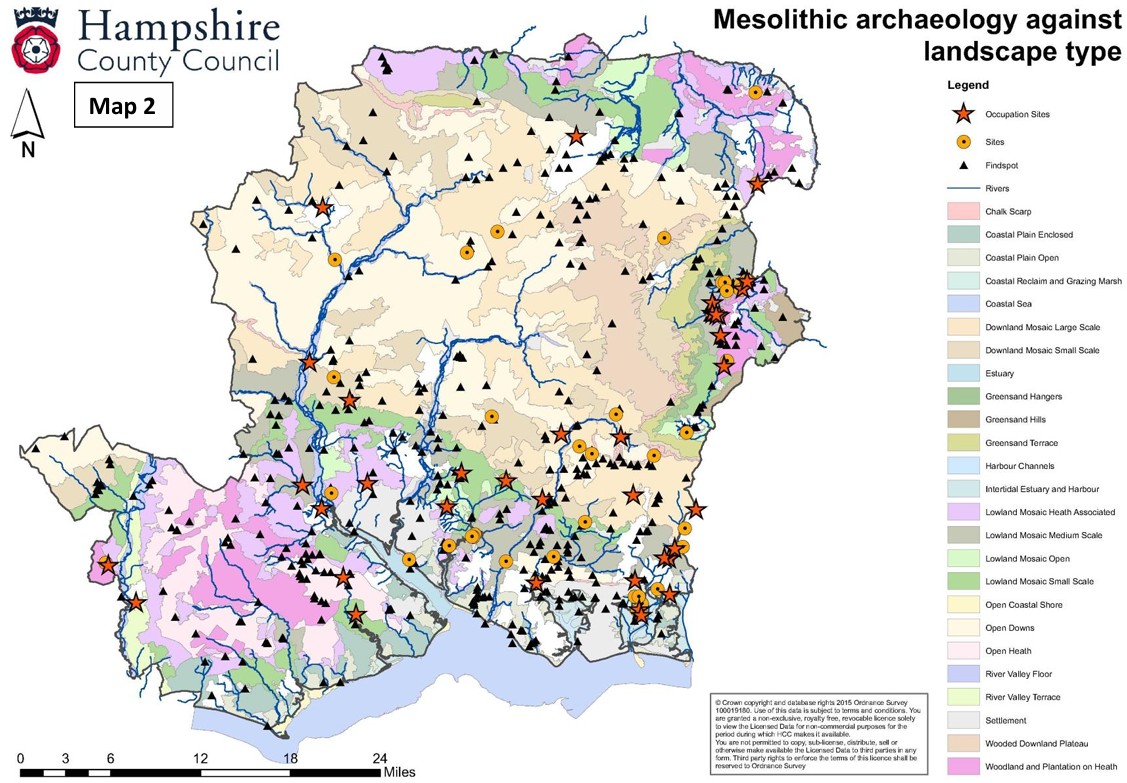

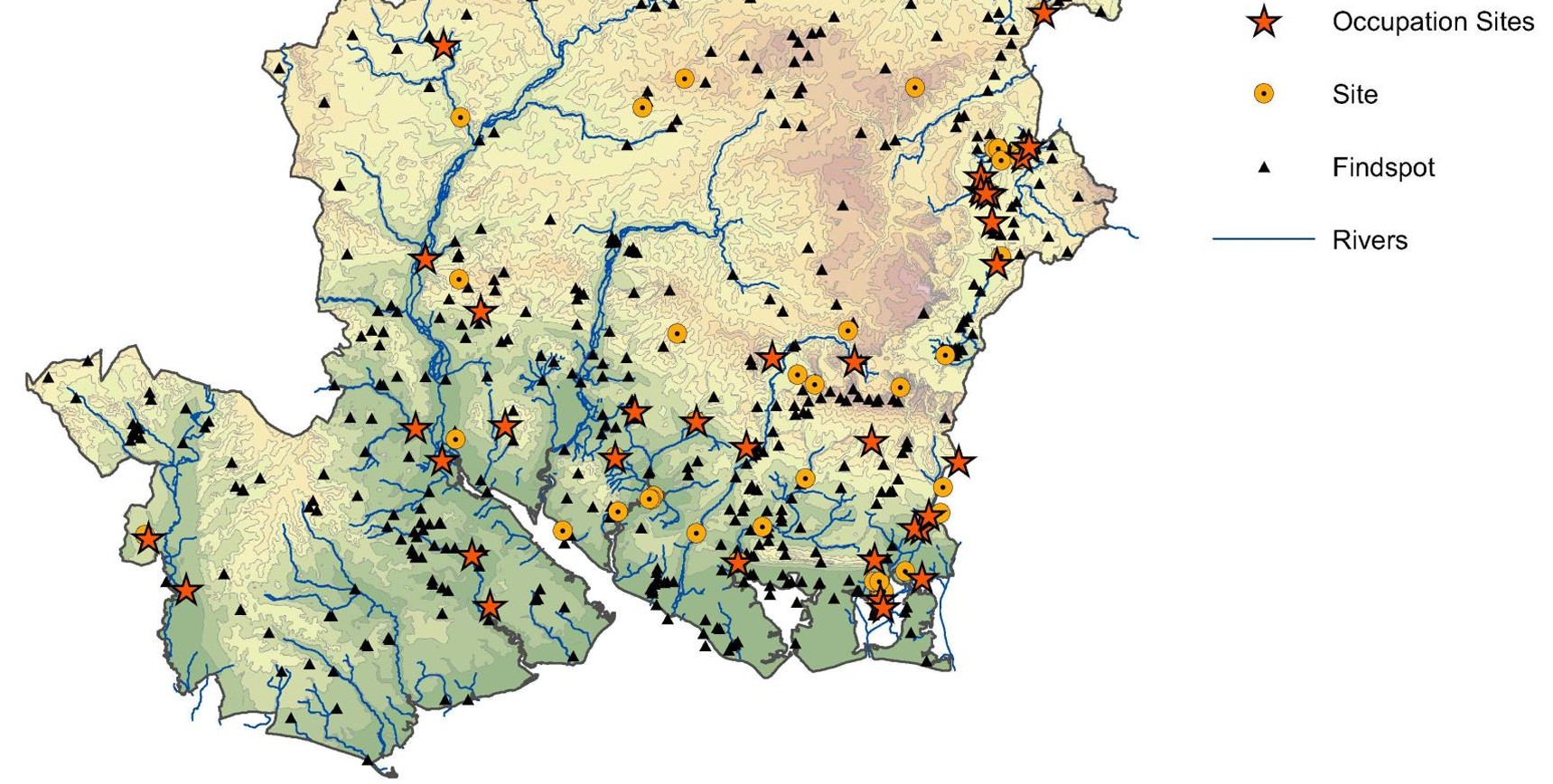

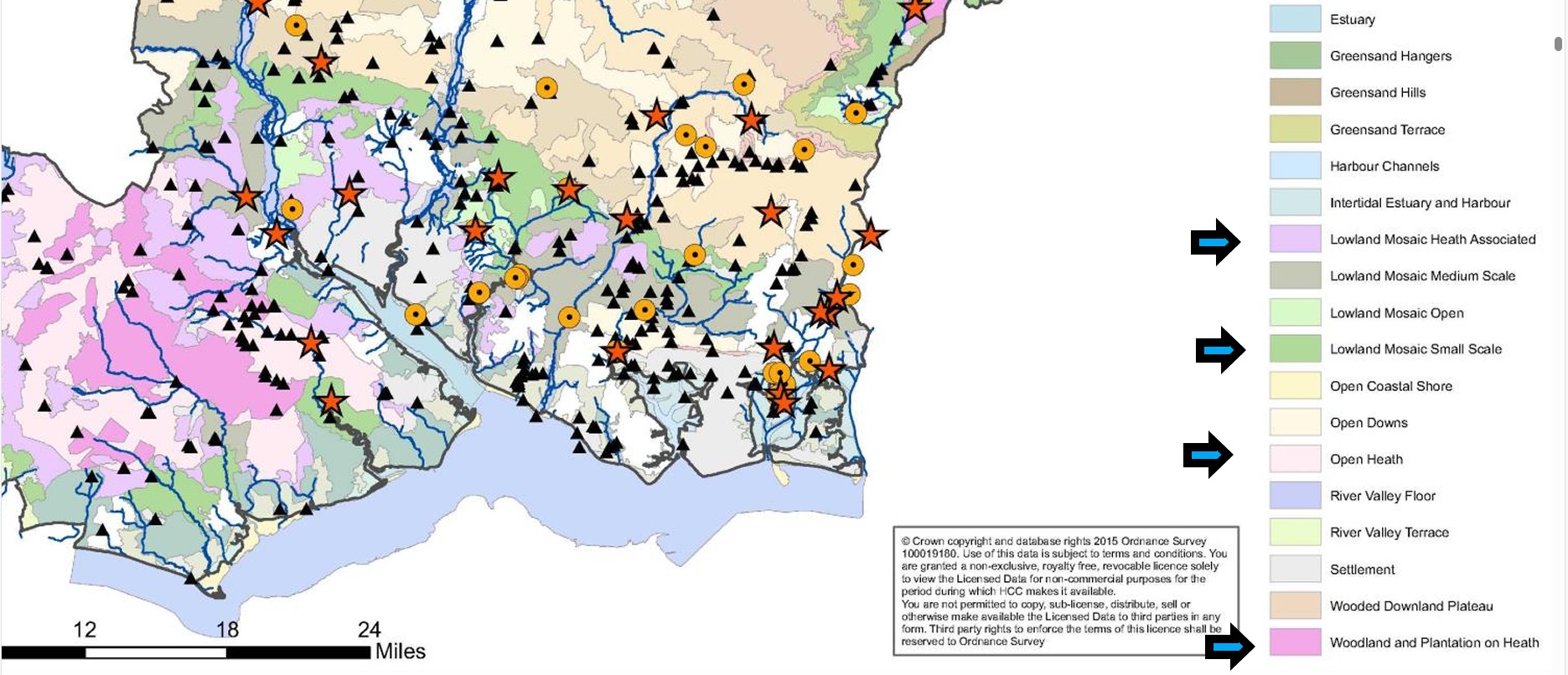

Above and below, Hampshire County Council Map of Mesolithic archaeology extracted from Atlas of Hampshire Archaeology.

Map 1 and map 2 - These show the distribution of evidence from the Mesolithic, sites and finds, which shows a concentration of activity through the

southern woodland, the central plain, river valleys and the East Hampshire heath. There is a notable spread between the River Wey, the River Loddon and

the top of the River Test. There is a notable lack of evidence across the extensive, arid chalk downs.

An article in Research Gate entitled Resource Assessment The Mesolithic in Hampshire refers mainly to Mesolithic evidence on the grasslands to the East of Hampshire and into Sussex. Also in an article in Hants Filed Club, entitled, MESOLITHIC RESEARCH IN EAST HAMPSHIRE. THE HAMPSHIRE GREENSAND.

Less intensive evidence to the West of Southampton Water. Very sparce in the New Forest and mid and North Hampshire.

Prehistoric evidence in Hampshire - Neolithic

Prehistoric evidence in Hampshire - Atlas of Hampshire's Archaeology - Neolithic

Prehistoric evidence in Hampshire - Bronze Age

Prehistoric evidence in Hampshire - Atlas of Hampshire's Archaeology - Bronze Age

An article in Research Gate entitled Resource Assessment The Mesolithic in Hampshire refers mainly to Mesolithic evidence on the grasslands to the East of Hampshire and into Sussex. Also in an article in Hants Filed Club, entitled, MESOLITHIC RESEARCH IN EAST HAMPSHIRE. THE HAMPSHIRE GREENSAND.

Less intensive evidence to the West of Southampton Water. Very sparce in the New Forest and mid and North Hampshire.

Rural Iron and Roman Age British Village Uncovered

FORDINGBRIDGE, ENGLAND—Cotswold Archaeology announced that a team of their archaeologists uncovered evidence for hundreds of years of intense Iron Age and Roman occupation at a site in Fordingbridge, Hampshire, prior to the construction of a new housing development. The investigation revealed more than 2,000 archaeological features spread across just two acres of a small river terrace, including pits, enclosures, ovens, and trackways. Most notable was the discovery of 15 roundhouses belonging to a previously unknown late Iron Age (first-century a.d.) rural settlement. Each house measured around 40 feet in diameter. Excavations in and around these structures found abundant evidence of domestic activities, including textile production and grain processing. One of the most exciting finds was a complete sandstone quern, or grinding stone, which are rarely, if ever, recovered whole and unbroken. During the later Roman phases, the settlement transformed from a residential site into more of an industrial complex, with evidence of large-scale metalworking and pottery production. To read in-depth about archaeology in southern England, go to "A Dark Age Beacon."

Prehistoric Parish of Eling, Hampshire

Well, approximately where the Parish of Eling would, some considerable time later, become established.

Prehistoric evidence in the Parish of Eling Hampshire

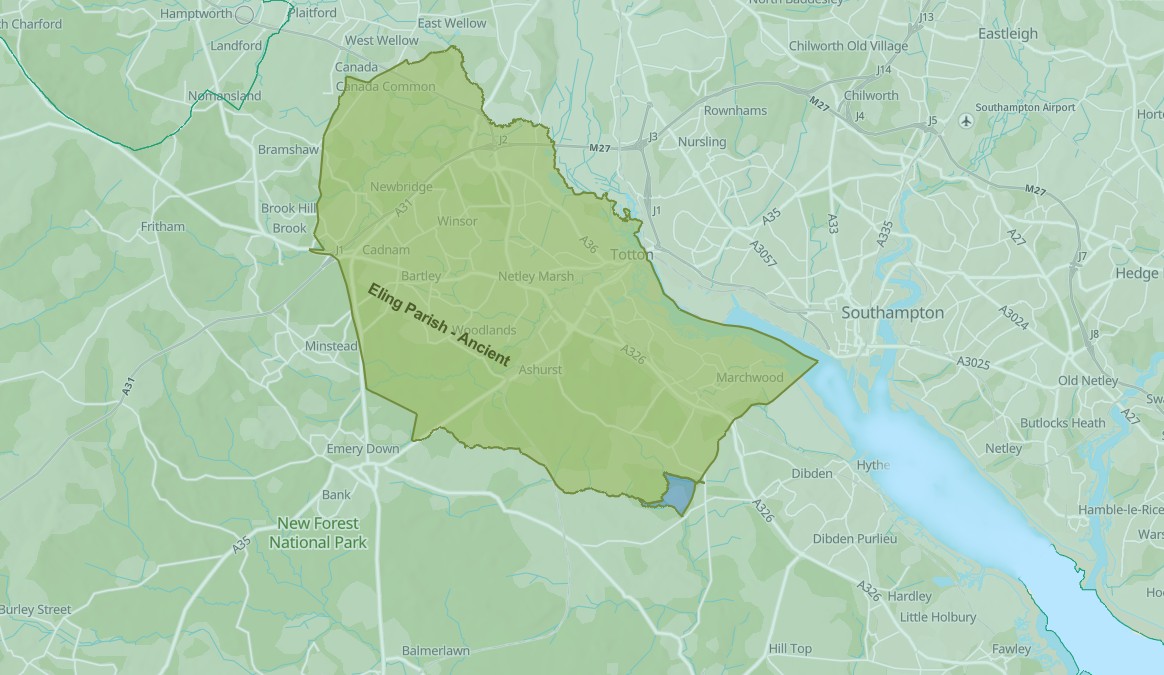

Lets start by establishing the area of Hampshire under consideration. In the South of the County of Hampshire, or Southamptonshire. To the West of the River Test and the town of Southampton. Nearly touching the County of Wiltshire to the North West, in the vicinity of Nomansland and Landford, shown on the map below. The New Forest further West of the parish. Adjoining the upper reaches of Southampton Water. To the South are the villages of Dibden, and Hythe.

A screenshot of the ESRI map with the superimposed Ancient Parish of Eling from the Story Map in the Overview above. Obviously not Prehistoric, but provides location context.

Prehistoric evidence in the Parish of Eling Hampshire - Mesolithic

Lets start by looking at the information from the Atlas of Hampshire Archaeology, which I have used in the Hampshire section, and zoom in to southern Hampshire. Looking particularly at the area to the left of Southampton and the River Test.

An extract of Hampshire County Council Map of Mesolithic archaeology taken from Atlas of Hampshire Archaeology. Using the previous information about the location of the Parish of Eling, there are three or four occupation sites and approximately 30 findspots.

An extract of Hampshire County Council Map of Mesolithic archaeology taken from Atlas of Hampshire Archaeology, with an approximate indication of the later Parish of Eling in blue.

Prehistoric evidence in the Parish of Eling Hampshire - Neolithic

Prehistoric evidence in the Parish of Eling Hampshire - Bronze Age

Money Hills - Barrow Cemetery

Testwood Lakes - Museum

Plaitford Barrow - Round Barrow(s)

Black Bush Plain - Barrow Cemetery

Fritham Butt - Round Barrow(s)

Iron Age - The Celts / Britons

Iron Age - The Celts / Britons

Iron Age evidence in Hampshire - Iron Age

The Iron Age is often considered to be within the Prehistoric otherwise dealt with. However, as this is also the story of The Celts, or Britions as the Romans called them, it deserves separate consideration. The tribes invaded and conquered by the Romans, and also remaining after the Romans left, and went back home.

Iron Age evidence in Hampshire - Atlas of Hampshire's Archaeology - Iron Age

Roman

Roman

From a quick internet search;

Roman evidence in Hampshire

Hampshire is rich in Roman evidence, with several key sites and discoveries that provide insight into the Roman occupation of the region. Here are some notable findings:

- Hamwic: Located near Southampton, this site is no longer intact but is still fascinating for its historical significance.

- Portchester Castle and Silchester: These are two major sites of Roman occupation, with Portchester Castle being particularly notable for its impressive Roman walls.

- Alice Holt and New Forest: Pottery from these areas has been excavated, indicating Roman pottery production.

- Horndean: This site, discovered in 2013, was adjacent to the Portsmouth to London road and revealed Roman ditches and pottery.

- Wickham: Excavations revealed a Roman road, roadside settlement, and wells, indicating a thriving settlement during the later 2nd century AD.

- Fordingbridge: An excavation uncovered a cluster of roundhouses, suggesting a previously unknown settlement of "roundhouses" during the late Iron Age to early Roman period.

These findings highlight the dynamic and significant presence of Romans in Hampshire, with ongoing archaeological research continuing to uncover more about their lives and activities in the region.

Source of some of the above, Tracing connections between Hampshire and our Roman History from Hampshire History

The Wickham reference is from Cotswold Archaeology, and Fordingbridge is both Cotswold Archaeology and Archaeology Magazine

Dark Ages

Darks Ages - Britons / Anglo Saxons / Vikings

Prehistoric

Domesday Book

Pending ...

Before 1600

Pending ...

1600 to 1800

Pending ...

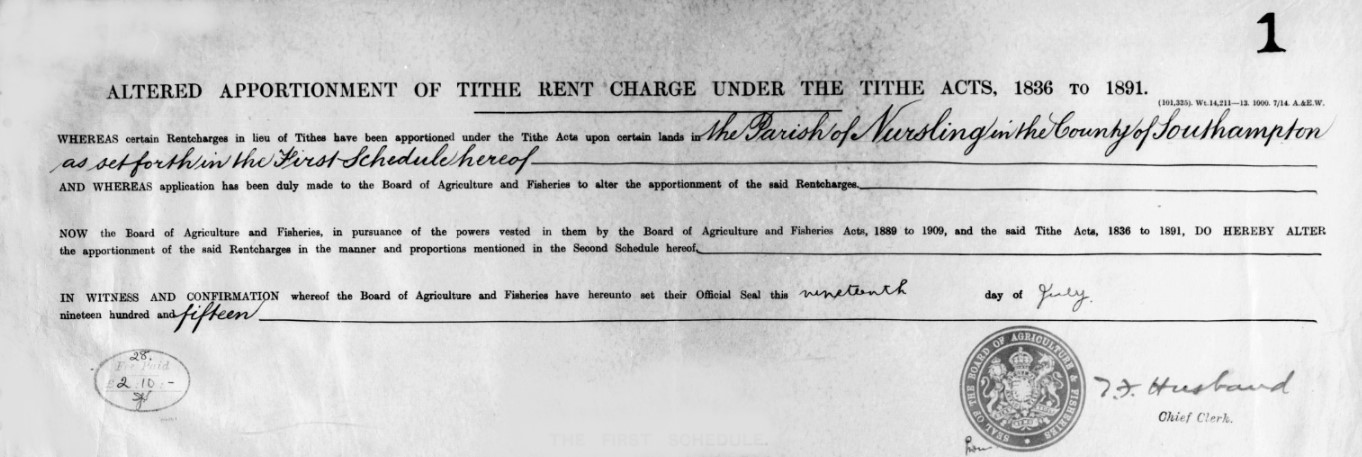

Tithe Apportionment and Map

Tithe Apportionment and Map

Background

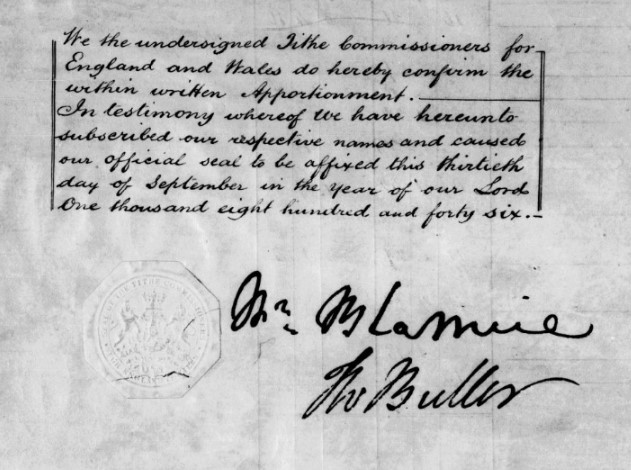

The Tithe Commutation Act 1836

An Act for the Commutation of Tithes in England and Wales. - 6 & 7 Will 4 c 71. Royal assent; 13 August 1836

Together with several amendments;

Act amended by Tithe Act 1839 (c. 62), Tithe Act 1842 (c. 54), Tithe Act 1860 (c. 93), Tithe Act 1878 (c. 42), Tithe Act 1891 (c. 8) and Tithe Act 1918 (c. 54)

The Tithe Act, 1936 (26 Geo. V and 1 Edw. VIII. C.43) abolished all tithe rent charges. Responsibility for tithe documents created under the tithe acts (1836, 1837, 1839, 1860, 1891) were placed under the charge of the Master of the Rolls, who has the authority to transfer them to an approved place of deposit. This responsibility is exercised by The National Archives: Historical Manuscripts Commission. The Master of the Rolls has issued Tithe (Copies of Instruments of apportionment) Rules 1960 (SI 1960/2440), as amended by the Tithe (Copies of Instruments of Apportionment) (Amendment) Rules 1963 (SI 1963/977)] concerning the care, custody, access to, and definition of tithe documents.

The start and end of Tithes.

Religion, of many faiths, the Established Church, the Pope, the Governments, and Kings of the time shaped the idea and practice of collecting tithes.

From a simple pious concept of the donation one tenth of your crop to the church, for charity, changed over time and created some very rich churches and some very poor people, and a degree of discontent.

Tithes lasted in England for over a thousand years, partly in goods and latterly as money.

All intertwined with a Norman, with Viking Blood, thinking he was the rightful successor to the English Throne, a Pope who wanted to bring Ireland into the European sphere, or should that read his sphere, and Henry VIII wanting to have a male heir to prolong the Tudor epoch. Little did he know Elizabeth I would be so good at being monarch. Power and politics, over centuries of time.

Splits in the Christian Church

There were three major schisms:

- 1) the one in the 5th century that split eastern Christendom in two;

- 2) the one the 11th century that divided the Latin church and the Byzantine church;

- and 3) the Reformation in the 16th century in which Protestantism arose and split from the Roman Catholic church.

2) On July 16, 1054, Patriarch of Constantinople Michael Cerularius was excommunicated, starting the “Great Schism” that created the two largest denominations in Christianity—the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox faiths.

3) The Reformation — more properly called the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation — was a 16th-century religious and political uprising against the authority of the Pope that led to was a schism in Western Christianity. It was initiated by Martin Luther with the publication of the “Ninety-five Theses” in 1517 and continued by Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin and other Protestant Reformers. The Reformation triggered the bloody the Counter-Reformation, which sucked in much of Europe, and lasted until the end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648. The Reformation led to the division of Western Christianity into different denominations such Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, Anabaptist and Unitarian. The Eastern Orthodox Christian church had split off in 1054.

The Reformation began as theological debate over real and perceived Church corruption. Early dissenters included John Wycliffe (1320-84) in England, and john Huss (burned as a heretic in 1415) in Bohemia. Martin Luther was from Germany. Other major players in the Reformation were Huldrych Zwingli of Zurich, John Calvin of Geneva and King Henry VIII of England

The Reformation was aided by the invigorated intellectual freedom of the Renaissance and spirit of nationalism in England, France, Germany and Bohemia. In the 16th century the church was corrupt and blemished by greedy clergy and decadent monks, extracting financial burdens from the laity to pay for their indulgences and ambitions. The General Councils of 15th century failed to reform he church. After the Reformation the power of the Catholic Church was greatly weakened

What is the relevance of these splits? The divisions within the Christian Church have in part contributed to the discontent leading to the Tithe Wars and the subsequent Tithe Commutation Act. The Act led to the creation of very useful set of documents for Family Historians, with information about people, places, and land usage.

Feudal system

A copy of some text from the ESRI Story Map of Whiteparish One Place Study

The feudal system and the Domesday Book

The feudal system was a way of organising society into different groups based on their roles. It had the king at the top with all of the control, and the peasants at the bottom doing all of the work.

How did the feudal system start?

The results created what's known as the Domesday Book. It actually described a wide range of ways in which people used the land, but historians suggested that it had a basic structure:

- King – owned all the land.

- Barons – the king gave some land to the barons in return for money and men for the army.

- Knights – the barons gave some of their land to the knights if they promised to fight when needed.

- Peasants – the knights gave a few strips of land to the peasants and the peasants had to share their produce with them. They were not allowed to leave and were not free men

In the Middle Ages, anyone who was higher up in this system than you was a 'lord' and of course the monarch had no one above them. What kept the system working was loyalty. Stay loyal and keep the land and wealth. Fail and your income was taken from you by your lord.

Centuries later the system was not hugely different and Tithes came into play.

Tithes were originally a tax which required one tenth of all agricultural produce to be paid annually to support the local church and clergy. After the Reformation much land passed from the Church to lay owners who inherited entitlement to receive tithes, along with the land.

The Tithe Acts of 1836 and 1936 abolished the old system, but two hundred years ago tithes were engraved upon the lives of the entire population: a source of income, luxury and avarice for the privileged; a tax at 2s

Before Tithes

Fifteenths and tenths, 1334

FIFTEENTHS AND TENTHS: QUOTAS OF 1334

'Fifteenths and tenths, 1334', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 4, ed. Elizabeth Crittall (London, 1959), pp. 294-303. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol4/pp294-303 [accessed 24 June 2021].

By the last quarter of the 13th century Englishmen had become familiar with a system of tax assessment which took no account of such old-fashioned assessments of wealth as hides or knight's fees. This new system of assessment was based on a valuation of certain personal property, usually described by the vague word 'movables'. Of this value Parliament had granted the king a fraction: the fraction itself varied from grant to grant but in each grant a greater fraction was levied on cities, towns, and royal demesne than on other areas. Thus in 1332 the townsman found himself contributing a tenth of his assessed movables but the countryman only a fifteenth. In addition there were some categories of goods which the collectors were instructed to ignore, and as a result the statistics from the collections deal only with those Englishmen and women who were wealthy enough to fall under the scrutiny of the local assessors. It is rather like an iceberg the size of whose submerged depths is unknown. In addition there was probably evasion and under-assessment everywhere.

Frustfield Hundred 274s.

- Abbotstone (in Whiteparish);50s 0d

- Alderstone (in Whiteparish);13s 4d

- Cowesfield (in Whiteparish);100s 0d

- Landford; 66s 8d

- Whelpley (in Whiteparish); 44s 0d

Whiteparish does not appear as a separate settlement in 1334, assuming that the (in Whiteparish) is a later addition when the table was constructed from the original data.

Tithe background

Tithe background

From Wikipedia, extracts from articles about Tithes and Tithe Commutation

A tithe (/taɪð/; from Old English: teogoþa "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government.

Church collection of religious offerings and taxes - England and Wales

The right to receive tithes was granted to the English churches by King Ethelwulf in 855. The Saladin tithe was a royal tax, but assessed using ecclesiastical boundaries, in 1188. The legal validity of the tithe system was affirmed under the Statute of Westminster of 1285. The Dissolution of the Monasteries led to the transfer of many rights to tithe to secular landowners and the Crown – and tithes could be extinguished until 1577 under an Act of the 37th year of Henry VIII's reign. Adam Smith criticized the system in The Wealth of Nations (1776), arguing that a fixed rent would encourage peasants to work far more efficiently.

The system gradually ended with the Tithe Commutation Act 1836, whose long-lasting Tithe Commission replaced them with a commutation payment, land award and/or rentcharges to those paying the commutation payment and took the opportunity to map out (apportion) residual chancel repair liability where the rectory had been appropriated during the medieval period by a religious house or college. Its records give a snapshot of land ownership in most parishes, the Tithe Files, are a socio-economic history resource. The rolled-up payment of several years' tithe would be divided between the tithe-owners as at the date of their extinction.

This commutation reduced problems to the ultimate payers by effectively folding tithes in with rents however, it could cause transitional money supply problems by raising the transaction demand for money. Later the decline of large landowners led tenants to become freeholders and again have to pay directly; this also led to renewed objections of principle by non-Anglicans.[39] It also kept intact a system of chancel repair liability affecting the minority of parishes where the rectory had been lay-appropriated. The precise land affected in such places hinged on the content of documents such as the content of deeds of merger and apportionment maps.

Tithe redemption

Rent charges in lieu of abolished English tithes paid by landowners were converted by a public outlay of money under the Tithe Act 1936 into annuities paid to the state through the Tithe Redemption Commission. Such payments were transferred in 1960 to the Board of Inland Revenue, and those remaining were terminated by the Finance Act 1977.

The Tithe Act 1951 established the compulsory redemption of English tithes by landowners where the annual amounts payable were less than £1, so abolishing the bureaucracy and costs of collecting small sums of money.

Ireland

From the English Reformation in the 16th century, most Irish people chose to remain Roman Catholic and had by now to pay tithes valued at about 10 per cent of an area's agricultural produce, to maintain and fund the established state church, the Anglican Church of Ireland, to which only a small minority of the population converted. Irish Presbyterians and other minorities like the Quakers and Jews were in the same situation.

The collection of tithes was resisted in the period 1831–36, known as the Tithe War. Thereafter, tithes were reduced and added to rents with the passing of the Tithe Commutation Act in 1836. With the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland by the Irish Church Act 1869, tithes were abolished.

Tithe War

The Tithe War (Irish: Cogadh na nDeachúna) was a campaign of mainly nonviolent civil disobedience, punctuated by sporadic violent episodes, in Ireland between 1830 and 1836 in reaction to the enforcement of tithes on the Roman Catholic majority for the upkeep of the established state church, the Church of Ireland. Tithes were payable in cash or kind and payment was compulsory, irrespective of an individual's religious adherence.

Tithe payment was an obligation on those working the land to pay ten per cent of the value of certain types of agricultural produce for the upkeep of the clergy and maintenance of the assets of the church. After the Reformation in Ireland of the 16th century, the assets of the church were allocated by King Henry VIII to the new established church. The majority in Ireland who remained loyal to the old religion were then obliged to make tithe payments which were directed away from their own church to the reformed one. This increased the financial burden on subsistence farmers, many of whom were at the same time making voluntary contributions to the construction or purchase of new premises to provide Roman Catholic places of worship. The new established church was supported by only a minority of the population, seventy-five percent of whom continued to adhere to Roman Catholicism.

Emancipation for Roman Catholics was promised by Pitt during the campaign in favour of the Act of Union of 1801 which was approved by the Irish Parliament, thus abolishing itself and creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. However, King George III refused to keep Pitt's promises. It was not until 1829 that the Duke of Wellington's government promoted and parliament enacted the Roman Catholic Emancipation Act, in the teeth of defiant royal opposition from King George IV.

But the obligation to pay tithes to the Church of Ireland remained, causing much resentment. Roman Catholic clerical establishments in Ireland had refused government offers of tithe-sharing with the established church, fearing that British government regulation and control would come with acceptance of such money.

(British rule in Ireland began with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169. Most of Ireland gained independence from Great Britain following the Anglo-Irish War as a Dominion called the Irish Free State in 1922, and became a fully independent republic following the passage of the Republic of Ireland Act in 1949. The papal bull Laudabiliter of Pope Adrian IV was issued in 1155. It granted the Angevin King Henry II of England the title Dominus Hibernae (Latin for "Lord of Ireland"). Laudabiliter authorised the king to invade Ireland, to bring the country into the European sphere. In return, Henry was required to remit a penny per hearth of the tax roll to the Pope. This was reconfirmed by Adrian's successor Pope Alexander III in 1172. When Pope Clement VII excommunicated the king of England, Henry VIII, in 1533, the constitutional position of the lordship in Ireland became uncertain. Henry had broken away from the Holy See and declared himself the head of the Church in England. He had petitioned Rome to procure an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Clement VII refused Henry's request and Henry subsequently refused to recognise the Roman Catholic Church's vestigial sovereignty over Ireland, and was excommunicated again in late 1538 by Pope Paul III. The Treason Act (Ireland) 1537 was passed to counteract this.

The Lordship of Ireland (Irish: Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between 1177 and 1542. The lordship was created following the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–1171. It was a papal fief, granted to the Plantagenet kings of England by the Holy See, via Laudabiliter. As the lord of Ireland was also the king of England, he was represented locally by a governor, variously known as justiciar, lieutenant, or lord deputy.

The kings of England claimed lordship over the whole island, but in reality the king's rule only ever extended to parts of the island. The rest of the island—known as Gaelic Ireland—remained under the control of various Gaelic Irish kingdoms or chiefdoms, who were often at war with the Anglo-Normans.

The area under English rule and law grew and shrank over time, and reached its greatest extent in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. The lordship then went into decline, brought on by its invasion by Scotland in 1315–18, the Great Famine of 1315–17, and the Black Death of the 1340s. The fluid political situation and Norman feudal system allowed a great deal of autonomy for the Anglo-Norman lords in Ireland, who carved out earldoms for themselves and had almost as much authority as some of the native Gaelic kings. Some Anglo-Normans became Gaelicised and rebelled against the English administration. The English attempted to curb this by passing the Statutes of Kilkenny (1366), which forbade English settlers from taking up Irish law, language, custom and dress. The period ended with the creation of the Kingdom of Ireland in 1542.)

The Kingdom of Ireland (Classical Irish: an Ríoghacht Éireann; Modern Irish: an Ríocht Éireann, pronounced [ənˠ ˌɾˠiːxt̪ˠ ˈeːɾʲən̪ˠ]) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of the Kingdom of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from 1542 until 1800. It was ruled by the monarchs of England and then the monarchs of Great Britain. The kingdom was administered from Dublin Castle by a viceroy appointed by the English king — the Lord Deputy of Ireland. A Parliament of Ireland, composed of Anglo-Irish and native nobles, was created. From 1661-1801, the administration controlled an army. A Protestant state church — the Church of Ireland — was established. Although styled a kingdom, for most of its history it was, de facto, an English dependency.

The Protestant Ascendancy, meeting in their Parliament of Ireland, passed the Acts of Union 1800 which abolished both the parliament itself and the kingdom.[5] The act was also passed by the Parliament of Great Britain. On the first day of 1801, a new state — the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland — was established which united the parliaments of Ireland and of Great Britain into a single legislature — the Parliament of the United Kingdom.)

Scotland

In Scotland teinds were the tenths of certain produce of the land appropriated to the maintenance of the Church and clergy. At the Reformation most of the Church property was acquired by the Crown, nobles and landowners. In 1567 the Privy Council of Scotland provided that a third of the revenues of lands should be applied to paying the clergy of the reformed Church of Scotland. In 1925 the system was recast by statute and provision was made for the standardisation of stipends at a fixed value in money. The Court of Session acted as the Teind Court. Teinds were finally abolished by section 56 of the Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc. (Scotland) Act 2000.

Tithe Commutation History

Tithe Commutation History

The extract below is from the The National Library of Wales. The same applied to England.

What Were Tithes?

Tithes were payments made from early times for the support of the parish church and its clergy. Originally these payments were made in kind (crops, wool, milk, young stock, etc.) and usually represented a tenth (tithe) of the yearly production of cultivation or stock rearing.

There were 3 types of tithe:

- Predial tithes were the products of crop husbandry - such as grain, woodland, and vegetables

- Mixed tithes were the products of animal husbandry - such as calves, lambs, wool and milk.

- Personal tithes were the profits of man's labour - such as fishing or milling (and largely insignificant after 1549).

It is more usual to refer to tithes as ‘Great Tithes’ and ‘Small Tithes’. The great tithes, also known as the ’rectorial tithes’, were payable to the rector and generally comprised the predial tithes of corn, grain, hay and wood while the small tithes, also known as the ‘vicarial tithes’, were payable to the vicar and comprised all other tithes

The ownership of the tithe was a property right that could be bought and sold, leased or mortgaged, or assigned to others. This resulted in many of the rectorial tithes passing into lay hands - particularly after the dissolution of the monasteries. These tithes then became the personal property of the new owners, or lay impropriators. After the sale of the tithes forfeited to the Crown in the 1530s, about 22.8% of the net value of tithes in Wales were held by lay impropriatorsat the time of commutation in 1836. A vicar usually continued to have the spiritual care of the parish and to receive the vicarial tithes.

From early times money payments had begun to be substituted for payments in kind. Fixed sums (moduses) were substituted for some categories of production, particularly for livestock and perishable produce; while adjustable payments known as compositions, which were sometimes assessed annually, were increasingly being substituted in local arrangements in latter years.

The National Archives holds a similar text as a guide, however, it was archived in 2015. Below is an extract from the archived version, just in case it disappears. The current version is In The National Archives Research Guides

The history of tithes

Originally, tithes were payments in kind (crops, wool, milk etc.) comprising an agreed proportion of the yearly profits from farming, and made by parishioners for the support of their parish church and its clergy. In theory, tithes were payable on

(i) all things arising from the ground and subject to annual increase - grain, wood, vegetables etc.;

(ii) all things nourished by the ground - the young of cattle, sheep etc., and animal produce such as milk, eggs and wool; and

(iii) the produce of man's labour, particularly the profits from mills and fishing.

Such tithes were termed respectively predial, mixed and personal tithes. Tithes were also divided into great and small tithes; generally speaking, corn, grain, hay and wood were considered great tithes, and all other predial tithes together with all mixed and personal tithes were classed as small tithes. It was common, but by no means universal, for the great tithes to be payable to the rector and the small tithes to the vicar of the parish.

During the dissolution of the monasteries, much church land - and in many cases also the accompanying rectorial tithes - passed into lay ownership. These tithes became the personal property of the new owners or lay impropriators. Usually a vicar continued to have spiritual oversight of the parish and to receive its vicarial tithes.

From early times money payments began to be substituted for payments in kind, a tendency further stimulated by enclosures, particularly the parliamentary enclosures of the late18th century. Enclosures were often made in order to improve the land and its yield, and had they proceeded without some arrangements respecting tithes, the rectors, vicars and lay owners of the tithes would have received an automatically increased income, as indeed they did when cultivation was improved without preliminary enclosure. One object of the Enclosure Acts was to get rid of the obligation to pay tithes. This could be done in one of two ways: by the allotment of land in lieu of tithes, or by the substitution either of a fixed money payment or of one which varied with the price of corn (hence the name corn rents applied to payments in lieu of tithes). The limits of the land allotted, or of the land charged with a money payment, were generally shown on a map attached to the Enclosure Award.

Tithe commutation from 1836

Statutory enclosure was a purely local affair, prompted by local landowners. Although much of the country was covered, in 1836 tithes were still payable in the majority of parishes in England and Wales. Scotland and Ireland have a different history: the Acts cited in this research guide did not apply there. In 1836, the government decided to commute tithes (i.e. to substitute money payments for payments in kind) throughout the country. The Bill received Royal Assent on 13 August 1836; three Tithe Commissioners were appointed, and the process of commutation began. Although the Tithe Act 1836 (6 & 7 Will IV, c.71) is a long and complicated piece of legislation, the underlying principle was the simple one of substituting for the payment of tithes in kind corn rents of the same sort as were already payable in many parishes under the authority of a local Enclosure Act. These new corn rents, known as tithe rentcharges, were not subject to local variation, but varied according to the price of corn calculated on a septennial average for the whole country. Existing corn rents were left unaffected: they continued to be paid according to the varied provisions of the local Acts which created them.

The first task of the Commissioners was to discover to what extent commutation had already taken place. Enquiries were directed to every parish or township listed in the census returns.

The initial process in the commutation of tithes in a parish was an agreement between the tithe-owners and landowners or, in default of agreement, an award by the Tithe Commissioners. Generally the next stage was the apportionment of payments, and the substance of the preceding agreement or award was then recited in the preamble of the instrument of apportionment.

Tithe maps

The Tithe Maps are by no means as uniform as the apportionments (see Section 6), varying greatly in scale, accuracy and size. At the outset, the Tithe Commissioners had attempted to secure a uniform and high standard. However in most cases there was no suitable map already in existence, and while there were many skilled land surveyors available, the expense of any new survey had to be met by the landowners. Insistence upon a fixed standard would have retarded the progress of commutation, so concessions therefore had to be made. When the 1836 Act was amended in the following year, a provision was inserted to the effect that, whilst every tithe map should be signed by the Commissioners, a map or plan should not be deemed evidence of the quantity of the land, or treated as accurate, unless it was sealed as well as signed by the Commissioners (Tithe Act 1837, s.1). Approximately 1,900 only of the tithe maps - about one-sixth of the whole - were sealed by the Tithe Commissioners, and it is these alone - called first-class maps - which can be accepted as accurate. The unsealed (or second-class) maps constitute a very mixed collection - indeed, some are little more than topographical sketches.

In many cases, discrepancies between apportionment and map subsequently created difficulties in the administration of payments and redemptions. At the time of the survey, when all the landowners concerned were well acquainted with the ground, the exact area of a piece of land or its precise delineation on a map might have appeared of little significance. The matter assumed more importance as time went on, particularly when readily-identifiable tithe areas vanished as a result of later developments. It is unnecessary to discuss in detail the problems of interpreting a tithe map; but it is well to bear in mind that reliance cannot be placed upon the area of individual tithe areas stated in an apportionment or computed from the tithe map, unless the map is sealed.

The numbers of the tithe areas on the map correspond to those in the schedules to the apportionment. These numbers are not consecutive.

Back to the The National Library of Wales.

The tithe maps

The accuracy of the maps depended on the skill of the local surveyors employed on the task. More than 200 different surveyors worked in Wales.

The first specification (British Parliamentary Papers, Session 1837, Vol. XLI 405) for the mapping proved to be over-ambitious. This was drawn up by one of the Assistant Commissioners, Lieutenant R K Dawson of the Ordnance Survey, and was intended to be at the scale of 3 chains to the inch (1:2,376) with a standardised set of symbols.

Unfortunately, this was not adopted, because the landowners had to pay the costs of the survey and many were unwilling, especially if they already had estate plans that could do the job.

Amending legislation had to be passed in 1837 permitting the presentation of less accurate maps, often on a smaller scale. Many of these maps were compiled from existing estate maps and involved very little new surveying.

Those maps that met the standard were calledfirst-class plans and received a seal from the Tithe Commissioners. The Tithe Commissioners refused their seal to inferior plans.

In Wales only 50 of 1,091 were sealed as first-class maps, mostly for Districts in Monmouthshire or Breconshire. The remainder were simply certified as being the documents on which the tithe rent-charge apportionment was based.

These second-class maps vary in scale and quality; there are some at the prescribed scale of 3 chains to the inch which for some reason were not sealed as first-class maps; while others are little more than topographical sketches and of no value for information about property boundaries, e.g. Llangeitho, Cardiganshire (1:7,920) and Nantglyn, Denbighshire (1:21,120). Some maps were simply enlargements of the Ordnance Survey One-inch maps.

How I make use of Tithe Apportionment and Maps

How I make use of Tithe Apportionment and Maps

This is both sharing with you the reader and helping me with some notes regarding the process for Tithe Apportionment articles, dataset, and ESRI Story Maps.

This hopes to provide a useful and consistent layout and content, which I suspect would be most beneficial in the collection of Tithe Apportionment articles.

Guide to Tithe Apportionment and Maps transcription and use

Guide to Tithe Apportionment and Maps transcription and use

The first part of this is to record the process of how I create information out of the historic data, followed by what I subsequently do with that information.

The end goal is to create sharable information for Family Historians and for myself. My choice of Parishes is reflective of my own Family Tree and the location of key ancestors in the period that the Surveys and Agreements were undertaken, about the 1840's

Introduction

Introduction

This element is fundamentally a guide for the transcription of the Tithe Allocation document and to the use of the associated spreadsheet.

The sections equate to the different tabs in the spreadsheet and the subsequent results in the associated webpage.

The sections also follow the process of creating the dataset.

Spreadsheet tables have a mix of direct entry, calculated fields, looked up data, and checking fields. Sometimes there is a colour bar above the titles to aid identifying the type of cells or fields in the column.

Generally the;-

- Direct entry are shown in a shade of blue, with light blue being the first pass of data entry.

- Calculating fields are headed with a yellow bar.

- Looked up data, i.e. information from other tables linked to this data, are headed with a brown bar.

- Checking fields, primarily to check data consistency, are headed with a red bar.

Creating the Dataset

Creating the Dataset

The original schedule is hand written on paper. Scans of those paper pages have been made. Fortunately, most of the handwriting is a lot easier to read that mine.

The images from those scans are available form the Hampshire Record Office and The Genealogist. The former also holds the original documents which can also be viewed by arrangement.

Analog images are very interesting but the data needs to be digitised to allow it to be readily accessed and interrogated.

Transcription from the scans is not very difficult, the handwriting is generally very legible, but is time consuming.

Key to creating the dataset is to have somewhere to put it, in an organised structured nature, which can subsequently be easily interrogated and analysed, producing reliable, meaningful, consistent, and repeatably results.

Primary Data

Creating the Dataset - Primary Data

Spreadsheet tab - Prime Data.

A form cell entry, not a table.

Most of the Primary Date will be found within or near the Agreement at the front of the Tithe Apportionment. There are also some checks back to the other parts of the spreadsheet but obviously these will not be correct until all of the other data is input and all the links refreshed.

There is a possibility that the total area stated in the Agreement is not the same as the sum of the parts elsewhere in the Agreement. The spreadsheet checks if the two match, however, if it shows a variance all that can be done is to check the input and transcription, and if they are correct, accept the historic variance.

Find the data and fill in the form accordingly.

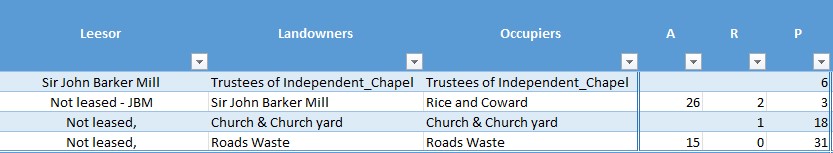

Summary

Creating the Dataset - Summary

Spreadsheet tab - Names of L and O.

A table where each row is a record, and each cell in that row is a field, or element of that record.

Find the Summary on the Tithe Apportionment, sometimes after the Schedule. It has a list of all the names and the total quantity of land and total rentcharge for each combination of Land owner and Occupier, and occasionally with an addition of Lessor, with Lessee as Land owner.

The first pass is only to capture the names of those people found in the Summary, ignoring the quantity and rentcharge columns.

Go to the tab 'Names of L and O' which is for Names of Landowner and Occupier. From the Summary enter, in the first three columns, the persons' name, normalised if necessary to given names followed by Surname. Suffix such as Esquire or & another, or & others are inserted in the second column, named appropriately. Part of the tab's calculation area finds the surname form the name and another part strips out any remaining underscores, "_". The third column is to indicate the category, such as Land owner or Occupier, or both, using the dropdown.

Entries such as Herself and Himself are transcribed as the persons name to facilitate separate record analysis.

Also Biddlecomb Widow and the like are transcribed Widow Biddlecome for consistent interpretation. Sad to think that there was a time that a woman was so much the wife of a man, that even on official documentation, they did not have a name, just that they were the Widow of that man.

On a paper copy it is implied that a list continues with the landowner, with multiple occupiers until the next landowner is written in. We are creating a dataset as well as a transcription so each record, or row, needs all of the information, not just a blank, ditto, or ". The name therefore needs to be copied down to all appropriate rows. The same applies to the Lessor if there is one.

Other columns in the tab are not relevant at this time and include data for cross-referencing between the Tithe listed people and my TNG database and the Census data.

Spreadsheet tab - Summary.

A table where each row is a record, and each cell in that row is a field, or element of that record.

The next step is to repeat the process on the tab 'Summary' but including the total quantity of land and total rentcharge this time. Yes, this is duplication of effort, but it is done to improve accuracy by double typing, The totals are also used to check the entries of the Schedule.

In the numerical fields, blanks can be left or leading zeros, up to the first number. However intermediate blanks must be replaced with a zero. I.e. ¦ " ¦ " ¦ 2 can be ¦ ¦ ¦ 2 ¦ but ¦ 4 ¦ " ¦ 8 ¦ has to be ¦ 4 ¦ 0 ¦ 8 ¦ .

At the end of the first page there is probably a total. In a column to the right headed page, input the page or image number and drag it down to cover all the entries for that page. Going back to the values input columns, and then curser down to the bottom. Use the page number to select the relevant information, or use the filter to select the page if that does not work. If all the selections are working, the total written in the Summary and that calculated on the spreadsheet should be correct. If they are not, check and recheck the transcription.

It is easier to do checks progressively, one page at a time, instead of waiting to do the check at the end and then trying to find what page the error is on followed by doing the same check as above for the page.

If it does tally correctly, proceed to the next page and continue. The checks would not highlight compensatory errors, but further checks happen latter.

At the end of the Summary there are totals for area and monies. The spreadsheet should correlate with the historic document.

Return to the Primary Data tab and add the Area Total, Acres, R, P after the names of the Tithe Commissioners.

Repeat with the Monetary Values for both Rent Charges.

The checks inspect the input against the same information on the historical documents.

There are some tabs on the spreadsheet that use the Summary as source. PT is for Pivot Table in these instances. The tabs are 'PT Summary Area Rent', 'PT Summary V Rent', 'PT Summary IM Rent', and 'PT Summary Area'.

Schedule

Creating the Dataset - Schedule

Spreadsheet tab - Plot registry.

A table where each row is a record, and each cell in that row is a field, or element of that record.

The Schedule has all the detailed data at the all important plot level.

Landowners and Occupiers and Numbers referring to the Plan

The plot number is the first entry, that is simple enough.

The next field only applies to some Schedules, where there is a Leasor at the top of the page. Which in turn renders what would normally be Landowner to become Leasee Landowner.

(Leasee Landowner) Landowner and Occupier are the next fields, which can either be by direct typing or by using the dropdowns which are fuelled by the data filled in 'Names of L and O' tab.

Name and Description of Lands and Premises and State of Cultivation

Lands and premises field is a copy of the schedule column Name and Description of Lands and Premises. This is a typing field. Sometimes there is very useful information in this field with names that can still be found on current or older maps. Other times it is a little sparse.

The State of Cultivation on the schedule is interested in land use to establish the Tithe. For those elements it is just typing into the column of the same name. However, I am also interested in other land use. Using the Description of Lands and Premises I make and assessment of the alternative usages, generally into one or more of the following usages.

| Name and Description of Land and Premises | State of Cultivation |

|---|---|

| House and Garden | {Residence} |

| Cottage and Garden | {Residence} |

| Yard and Buildings | {Premises} |

| Farm Yard and Buildings | {Premises} |

| Blacksmiths Shop | {Retail} |

| Willow Bed and Water | {Water} |

| Roadway | {Road} |

| Waste | {Waste} |

| Chapel | {Church} |

| Common | {Common} |

| Pleasure Gardens | {Pleasure Gardens} |

| Orchard | {Orchard} |

| Plantation | {Plantation} |

| House, Blacksmith's Shop, and Garden | {{Residence}{Retail}} |

| ??? Inn and Garden | {{Residence}{Retail}} |

| House, Blacksmith's Shop, Buildings, Garden, and Yard | {{Residence}{Retail}{Premises}} |

| House and Pleasure Garden | {{Residence}{Pleasure Gardens}} |

| Mansion House, and Pleasure Gardens | {{Residence}{Pleasure Gardens}} |

| Mansion House, Buildings, and Pleasure Gardens | {{Residence}{Pleasure Gardens}{Premises}} |

The new categories of use are enclosed in braces { } to distinguish the entry apart form the transcription. Multiple uses are allocated any combination of the new categories, enclosed in a further set of braces {{ }{ }}, although avoid {{ a }{ b }} and {{ b }{ a }} as this will just collate as two entries when it is only one.

I should point out at this point that in my opinion the description 'Garden' is not how we would construe the term today. Today we might think of a front or back garden with perhaps flowers and a lawn, laid out to look good. With some of the front gardens converted as somewhere to park cars. I suspect that in 1800's 'Garden' was more akin to market garden or vegetable patch.

| Aside |

Following the end of the war in the 1940's, 50's and 60's the UK went on something of a building spree, with thousands of council houses being built. Part replacing bombed out buildings and part slum clearance. I was brought up in my early years in one such house. I recall reading somewhere that a lot of council houses built then had relatively large gardens to facilitate home production, farming on a small scale. These micro farms may have included animals, a pig, or some chickens, but mainly fruit and vegetables. A continuation of the wartime make do and carry on, self reliance. Times have changed, and as a society we moved away from grow your own, so the gardens have become more about flowers and lawns. We could be at the beginning of a move towards a return to grow your own. See Also Historic England on Post War council housing estates

|

Quantities in Statute Measure

In the numerical fields, blanks can be left or leading zeros, up to the first number. However intermediate blanks must be replaced with a zero. I.e. ¦ " ¦ " ¦ 2 can be ¦ ¦ ¦ 2 ¦ but ¦ 4 ¦ " ¦ 8 ¦ has to be ¦ 4 ¦ 0 ¦ 8 ¦ .

The area of the plot numbers are ¦ A. ¦ R. ¦ P. ¦ meaning Acre, Rood (Rod), and Perch. With 40 perch to a rood and 4 rood to the acre.

| Aside |

One Acre is the area that could be ploughed by a team of eight oxen in one day. Measuring land for ownership (and taxation) is a very ancient concept, as is the word ‘acre’, which occurs in many old languages and translates as ‘open field’. The area thus described was originally a strip of land (a long furrow, which gave rise to the word furlong, an old measurement of length) that a ploughman and his yoke of two oxen could turn over in an average day’s work – a strip being easier to plough than a square, as there were fewer turning points required. Acres. Later an acre was more accurately measured as an area which is equivalent to 10 chains by one chain. A chain is now standardised as 66 feet (20.18 m), so the actual area covered by an acre is 660 feet by 66 feet, which (to save you the maths) converts to near enough 4,048 square metres. To visualise this, a professional football (soccer) field covers an area of two acres, so one team’s half is an acre. Thus a hectare, which is approximately 2 1⁄2 acres, takes up both halves of the playing area, plus the land around it between players and spectators. Roods & perches. These are subdivisions of an acre. There are four roods in an acre, and in turn a rood contains 40 perches. As a rood is a quarter of an acre, it contains 1.012 square metres – about the size of two tennis courts. Each of the 40 perches in a rood thus consists of just over 25 square metres – the size of one of the net-side playing areas of the tennis court. One chain is also the distance between wickets on a cricket pitch. The chain (abbreviated ch) is a unit of length equal to 66 feet (22 yards), used in both the US customary and Imperial unit systems. It is subdivided into 100 links. There are 10 chains in a furlong, and 80 chains in one statute mile. In metric terms, it is 20.1168 m long.

|

Each plot has an area measurement and therefore an entry under Quantities in Statute Measure. However, not every plot has an entry under rent-charge.

Amount of Rent-Charge apportioned upon the several Lands, and Payable to the Vicar / Rector / Impropriator

There are now two groups of columns, one group regarding the rent-charge payable to the vicar, and the other to the Impropriator.

Each group separated into ¦ £. ¦ s. ¦ d. ¦. £ s d being Pounds, shillings, and pence. With 12 pence to the shilling and 20 shillings to the pound. If you are of a certain age you will be able to add up the values easily.

Sometimes the Tithe Apportionment pro-forma only has one group of rent-charge, as is the case with Nursling, with the charge payable to the Rector. I don't think it makes much difference but I have decided to record the entries for the Rector under the columns for Impropriator. I will hide the columns for the vicar for the time being to aid filling in the data.

Applies to both Quantities in Statute Measure and Rent-Charge

Where there is one Landowner and one occupier for a single plot there is a single entry for each such set.

Where a Landowner has a number of occupiers across numerous plots, there might be a subtitle for that landowner. In such a case add a sub-subtitle into the column headed Sub title info. The numbers entered adjacent to such annotations are treated differently in the totals calculations to avoid double counting. Adding the sub totals in this way should allow the entered data to look similar to the original document. Which should allow better visual checking of data entry.

At the end of the each page there may be a total. This would be annotated sub-total.

If there is a total at the end of the page set the filters to that page and filter out the sub-subtotals and the subtotal annotations in the column headed Sub title info,and the totals displayed should equal those shown on the original document. If not firstly check for the correct page designations, and filter settings. Then check the entries. Then check the entries again. If after all these checks there is still a variance, check the arithmetic on the original document.

Whatever the outcome of the checks, transcribe the document as it is, and make a note in the notes column of the variance and suspected cause. So if the Tithe Apportionment has the rent-charge sub-total of £ 3 5s 10p but it should have totaled £ 3 6s 10p write the original £ 3 5s 10p and note the 1s variance. Expect that variance to show up again in the totals.

Obviously, if the error is found to be an incorrect transcription/data entry then that is corrected. A 3 looks like and 8, but the totals confirm that it was a 3, go back and change it from a 8 to a 3.

The same applies to the sub-subtotals as you work your way down the page. You can either use the filtering method or hone your arithmetic skills other than decimal, with 40, 4, and 12, and 20, being the shift to the next column.

If you do use the filtering method, there is a yellow box under the data input area of the table which does the arithmetic for you. But don't forget to either filter out the sub-subtotals or do it before entering the data, otherwise you will get incorrect totals. A reminder, this procedure is to check your data entry, not the Tithe Apportionment arithmetic.

In some instances the occupier or landowner may be split across more than one page with the use of 'carry forward' and 'brought forward'. I have not created a mechanism for dealing with this as it is not required in a continuous record set. It is very much a paper based way of doing things. A very good way, I might add, for paper. So although the record set should look similar to the original, this is left out, both the 'carry forward' at the bottom of the page, and 'brought forward' at the top of the following page. However, I do consider it prudent to think of it as a sub-total and check if my input thus far equals the stated 'carry forward' figure by using the filters as above. As long as that is the case, I just move on and discard them. If not, I find the cause of the variance.

Additional information

Creating the Dataset - Additional information

Spreadsheet tab - Plot registry.

Still working on the Plot Registry and data from the The Schedule.

Name and Description of Lands and Premises and State of Cultivation

| Number of dwellings | Sub total info |

Where the information from the original document implies a residence, such as House and Garden or Cottage and Garden add a 1 to the column headed 'Number of dwellings'. If is states Two Cottages, add a 2, etc.

Ultimately, that will provide the total number of dwellings covered by the Tithe Apportionment survey, which can be compared to the appropriate Census.

Sub total info has been dealt with above.

| Include in Landowners report | Include in Occupiers report | Owner Occupier | Probable Residence |

Include in Landowners report / Include in Occupiers report

Are both part of data checking.

Owner Occupier

Owner Occupier is actually a calculated field not a direct entry. It reports true if the entered Landowners and Occupiers Names are the same.

Probable Residence

Probable Residence is a simple drop down 'True' statement where the description suggests that there is one or more dwellings on the plot. It could have been a calculated field based on the 'Number of dwellings' column but this gives a degree of data checking.

Place named

I have recently added a column headed 'Place named', which is intended as a 'TRUE' or blank. With reference to the Description on the Schedule the are several named fields which could be useful, but they don't qualify for a 'TRUE' in this column. A named inn, a church, or named mansion are all examples which would be 'TRUE'. The idea being that when the data is filtered to 'TRUE' the named places can be searched for on old maps. Once a particular named place is located on both the Tithe Map and an old map it is easier to start matching plots on the Tithe Map to fields and places on an old map, which can then be used to create the associated latitude and longitude.

Page and notes are further into the 'Engine' as shown below.

The page is just the page number of the Tithe Apportionment for this particular Parish. The Page number can also be used to create page totals and to check the data entry of the figures where the Tithe Apportionment has page totals. A change of page number generates a broken underline at the first six fields of data entry.

Notes are just that, either notes on the Tithe Apportionment document or your own notes. I do not normally add the coded / accounting annotations found at the edge of some rows on the Tithe Apportionment.

I use the notes to record variations in arithmetic (errors on the original Tithe Apportionment) - rare, but do occasionally show up.

Checks

As well as the double entry typing as part of the checks there are both overall and detailed checks.

The basic overall checks are included in the Primary Data tab. Rudimentary TRUE or FALSE statements which combine to either a sad or happy face.