Our part in the Fall of the Roman Empire

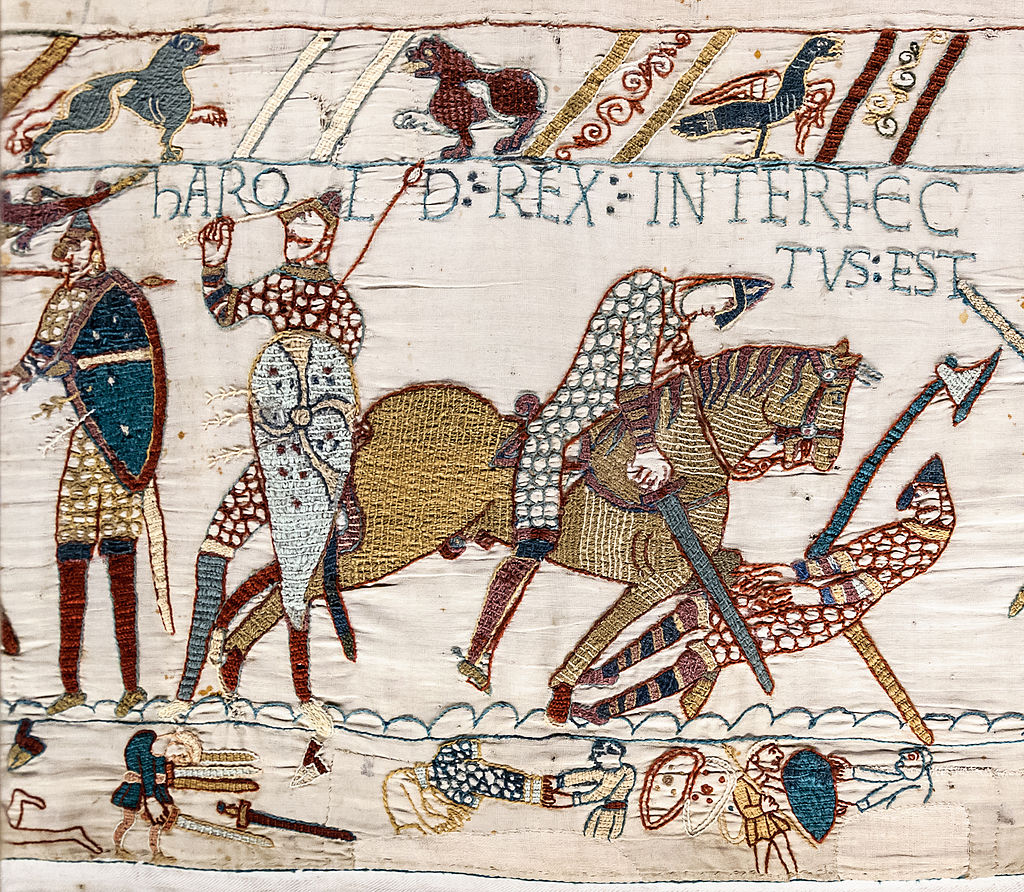

There are some that say the Fall of the Roman Empire commenced with Valens, Roman Emperor of the East, when he fought the Goths at the Battle of Adrianople, near Hadrianopolis in Thrace. Which he both lost, and lost his life at. The beginning of the end.

See my article below to read about some of the goings on about that time.

However, I believe that the die was cast a long time before that, and it was not because of a battle with an external force, such as the Goths. No, the whole system had failed and was marching inexorably to its own self destruction.

My article below is a small slice of time presented in an approximate timeline, with information extracted from Wikipedia, which in turn lists many sources. It includes murders, children being declared Emperors, and then dying young. Power struggles, usupers, and political manipulation. Between ancestors on my Family Tree.

Follow my Tree back a little further to another relative;-

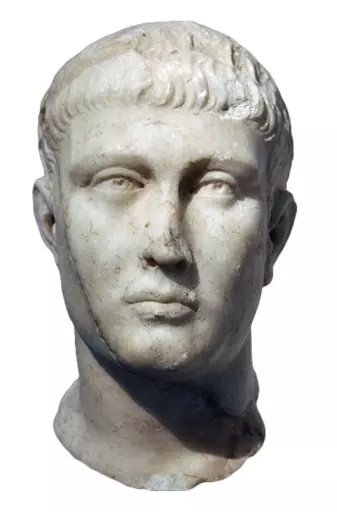

Constantine I Constantine the Great, Roman Emperor

BIRTH ABT. 27 FEB 272 • Niš, Serbia

DEATH 22 MAY 337

paternal grandfather of wife of great-granduncle of wife of uncle of husband of sister-in-law of 15th great-grandaunt of wife of 32nd great-grandfather

House of Constantinian

He died in the year 337, as did a lot of other people. Frequently relatives.

I shall call this the Constantine Purge of 377

Another extract from Wikipedia, this time about Constantine II.

On 1 March 317, he was made caesar. In 323, at the age of seven, he took part in his father's campaign against the Sarmatians. At age ten, he became commander of Gaul, following the death of his half-brother Crispus. An inscription dating to 330 records the title of Alamannicus, so it appears that his generals won a victory over the Alamanni. His military career continued when Constantine I made him field commander during the 332 winter campaign against the Goths. The military operation was successful and decisive, with 100,000 Goths reportedly slain and the surrender of the ruler Ariaric. He was married prior to 336, although his wife’s identity remains unknown.

While Constantine I had intended for his sons to rule together with their cousins Dalmatius and Hannibalianus, soon after his death the army slaughtered almost all of their male relatives, including Dalmatius and Hannibalianus. Burgess observed from numismatic evidence that Constantine II and his brothers “not only seem not to have fully accepted the legitimacy of Dalmatius and viewed him as an interloper, but also appear to have communicated with one another on this point and agreed on a common response.”

He was soon involved in the struggle between factions rupturing the unity of the Christian Church. The Western portion of the empire, under the influence of the Popes in Rome, favoured Nicene Christianity over Arianism, and through their intercession they convinced Constantine to free Athanasius, allowing him to return to Alexandria. This action aggravated Constantius II, who was a committed supporter of Arianism.

The three brothers were not named as Augusti until 9 September 337, when they gathered together in Pannonia and divided the Roman territories among themselves. Constantine received Gaul, Britannia and Hispania.

In what seemed to be an attempt to distance themselves from the massacre, the three brothers proceeded to print coins of Theodora, whom their murdered relatives had been descended from.[6] The evidence indicates that Constantine II was the one responsible for designing and producing the coinage at the start, as well as convincing his brothers to do the same. Woods considered it to suggest that he was more sympathetic to Theodora’s memory than his brothers, possibly because his wife may have been a granddaughter of Theodora.

It appears that Constantine was left unsatisfied with the results of their meeting, as he soon complained that he had not received the amount of territory that was his due as the eldest son. Annoyed that Constans had received Thrace and Macedonia after the death of Dalmatius, Constantine demanded that Constans hand over the African provinces, to which he agreed in order to maintain a fragile peace. Soon, however, they began quarreling over which parts of the African provinces belonged to Carthage, and thus Constantine, and which belonged to Italy, and therefore Constans. Even after campaigning against the Alamanni in 338, he continued to maintain his position. The Codex Theodosianus recorded Constantine’s legislative intervention in Constans’ territory through issuing an edict to the proconsul of Africa in 339.

In 340 Constantine marched into Italy at the head of his troops to claim territory from Constans. Constans, at that time in Naissus, detached and sent a select and disciplined body of his Illyrian troops, stating that he would follow them in person with the remainder of his forces. Constantine was killed by Constans's generals in an ambush outside Aquileia. Constans then took control of his deceased brother's realm. After his death, Constantine was subjected to damnatio memoriae, which his other brother Constantius II also followed.

Family squabbling on an epic scale

If this is how brothers and cousins behave, and interact, how do we think the generals and politicians fared!!

Through all this generals, politicians, and the church, of various flavours, tried to manipulate and control things.

The state continued to implode. It was broken to the core. It was beyond it's sell by date, and was inexorably progressing towards collapse, which ultimately it did.

Not fistycuffs at a disfunctional family wedding, but wars, civil wars, where the intent is to obliterate, not only the opposition, but anybody who might become the opposition.

An Empire destined to fail way before the devastating Battle of Adrianople, facing the Goths.

Further reading about the chaotic reigns of the sons of Constantine the Great

A sad tale, and not a surprising prelude to the Fall of the Roman Empire.

Is this history repeating itself? How many times has this played out in the age of the Roman Empire?

Our part in the Roman Empire

Our part in the Roman Empire

Theodosius I (11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was a Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two civil wars, and was instrumental in establishing the creed of Nicaea as the orthodox doctrine for Christianity. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule the entire Roman Empire before its administration was permanently split between the West and East.

Theodosius the Great is in my Family Tree and is my;-

great-grandfather of wife of uncle of husband of sister-in-law of 15th great-grandaunt of wife of 32nd great-grandfather, on my maternal side.

Valentinian the Great is also in my Family Tree and is my;-

2nd great-grandfather of wife of uncle of husband of sister-in-law of 15th great-grandaunt of wife of 32nd great-grandfather, on my maternal side.

So, neither are particularly close, and a lot of generations ago.

Also mentioned below are some Goths, under the command of Athanaric. He is considered the first king of the Visigoths, or Thervingi, who later settled in Iberia, where they founded the Visigothic Kingdom.

More Goths but this time Ostrogoths, under Alatheus.

It should be noted that this article is almost entirely constructed with snippets or extracts from Wikipedia, who I thank for so much information.

Theodosius the Great was not of a family of Roman Emperors. His father was high-ranking general, Theodosius the Elder. Theodosius the Elder was patriarch of the imperial Theodosian dynasty (r. 379–457), The House of Theodosius.

The House of Theodosius |

The House of Valentinian |

The House of Valentinian |

||

Theodosius the Elder |

Valentinian I, Valentinian the Great,

|

Valens,

|

||

|

Valentinian was born in 321 at Cibalae (now Vinkovci, Croatia) in southern Pannonia into a family of Illyrian origin. Valentinian and his younger brother Valens were the sons of Gratianus (nicknamed Funarius), a military officer renowned for his wrestling skills. Gratianus was promoted to comes Africae in the late 320s or early 330s, and the young Valentinian accompanied his father to Africa. However, Gratian was soon accused of embezzlement and retired. Valentinian joined the army in the late 330s and later probably acquired the position of protector domesticus. Gratian was later recalled during the early 340s and was made comes Britanniae. After holding this post, Gratianus retired to the family estate in Cibalae. |

Valens and his brother Valentinian were born, in 328 and 321 respectively, to an Illyrian family resident in Cibalae (Vinkovci) in Pannonia Secunda. Their father Gratianus Funarius, a native of Cibalae, had served as a senior officer in the Roman army and as comes Africae. The brothers grew up on estates purchased by Gratianus in Africa and Britain. Both were Christians, but favored different sects: Valentinian was a Nicene Christian and Valens was an Arian Christian (a "Homoean"). In adulthood, Valens served in the protectores domestici under the emperors Julian and Jovian. According to the 5th-century Greek historian Socrates Scholasticus, Valens refused pressure to offer pagan sacrifices during the reign of the polytheist emperor Julian. | |||

|

Theodosius the Elder was magister equitum (Master of Horse) under Valentinian I (321 – 17 November 375), sometimes called Valentinian the Great, who was Roman emperor from 364 to 375. He ruled the Western half of the empire, while his brother Valens ruled the East.

|

In 350, Constans I was assassinated by agents of the usurper Magnentius, a commander who proclaimed himself emperor in Gaul. Constantius II, older brother of Constans and emperor in the East, promptly set forth towards Magnentius with a large army. The following year the two emperors met in Pannonia and fought the Battle of Mursa Major, which ended in a costly victory for Constantius. Two years later Magnentius killed himself after another defeat at the Battle of Mons Seleucus, leaving Constantius sole ruler of the empire. It was around this time that Constantius confiscated Gratianus' property, for supposedly showing hospitality to Magnentius when he was in Pannonia. Despite his father's fall from favour, Valentinian does not seem to have been adversely affected at this time, making it unlikely he ever fought for the usurper. It is known that Valentinian was in the region during the conflict, but what involvement he had in the war, if any, is unknown. The conflict between Magnentius and Constantius had allowed the Alamanni and Franks to take advantage of the confusion and cross the Rhine, attacking several important settlements and fortifications. In 355, after deposing his cousin Gallus but still feeling the crises of the empire too much for one emperor to handle, Constantius raised his cousin Julian to the rank of Caesar. With the situation in Gaul rapidly deteriorating, Julian was made at least nominal commander of one of the two main armies in Gaul, Barbatio being commander of the other. At the news of Julian's death on a campaign against the Sassanids, the army hastily declared Jovian the new emperor. He extricated his soldiers from Persian territory by agreeing to a humiliating peace treaty, then started back to Constantinople, dying in mysterious circumstances before he reached the capital. During Jovian's brief reign Valentinian was promoted to tribune of a Scutarii (elite infantry) regiment, which Hughes considered to reflect the emperor’s trust in him, and dispatched to Ancyra. A meeting of civil and military officials was convened at Nicaea to choose a new emperor. Salutius, who had already refused the throne after Julian's death, now did so again, first for himself and then on behalf of his son. Two different names were proposed: Aequitius, a tribune of the first Scutarii, and Januarius, a relative of Jovian's in charge of military supplies in Illyricum. Both were rejected; Aequitius as too rough and boorish, Januarius because he was too far away. As a man well qualified and at hand, the assembly finally agreed upon Valentinian, and sent messengers to inform him in Ancyra.

Valentinian accepted the acclamation on 25 or 26 February 364. As he prepared to make his accession speech the soldiers threatened to riot, apparently uncertain as to where his loyalties lay. Valentinian reassured them that the army was his greatest priority. According to Ammianus the soldiers were astounded by Valentinian's bold demeanour and his willingness to assume the imperial authority. To further prevent a succession crisis he agreed to pick a co-Augustus, a decision that might be construed as a move to appease any opposition among the civilian officials in the Eastern part of the Empire and reassure eastern officials that someone with imperial authority would remain in the east to protect their interests. Valentinian selected as co-Augustus his brother Valens at Constantinople on 28 March 364. This was done over the objections of Dagalaifus, the magister equitum. Ammianus makes it clear that Valens was subordinate to his brother. The remainder of 364 was spent delegating administrative duties and military commands. |

Julian was killed in battle against the Persians in June 363, and his successor Jovian hastened towards Constantinople to secure his claim to the purple. Before reaching the capital, Jovian died unexpectedly at Dadastana in February 364. The Latin historian Ammianus Marcellinus relates that Valentinian was summoned to Nicaea by a council of military and civil officials, who acclaimed him augustus on 25 February 364. Valentinian appointed his brother Valens tribunus stabulorum (or stabuli) on 1 March 364. It was the general opinion that Valentinian needed help to handle the administration, civil and military, of the large and unwieldy empire, and, on 28 March, at the express demand of the soldiers for a second augustus, he selected his brother Valens as co-emperor at the Hebdomon, before the Constantinian Walls. Both emperors were briefly ill, delaying them in Constantinople. As soon as they recovered, the two augusti travelled together through Adrianople and Naissus to Mediana, where they divided their territories. Valens obtained the eastern half of the Empire: Greece, the Balkans, Egypt, Anatolia and the Levant as far as the border with the Sasanian Empire. Valentinian took the western half, where the Alemannic wars required his immediate attention. The brothers began their consulships in their respective capitals, Constantinople and Mediolanum (Milan).

|

||

Campaigns in Gaul and Germania |

||||

|

In 368, Theodosius was raised to the high Roman military rank of comes rei militaris and sent to northern Gaul and Britannia to recover the lands lost to the Great Barbarian Conspiracy in the previous year. Theodosius was given command of part of Valentinian's comitatensis (the Imperial Field Army) and early in the year he marched on Bononia (Boulogne-sur-Mer), Rome's harbour on the Channel. Taking advantage of a break in the weather Theodosius crossed the Channel, landing at Rutupiae (Richborough), leaving the bulk of his troops in Bononia to await clearer weather. At Rutupiae Theodosius started gathering intelligence on the situation in Britain; he found out that the troops in Britain had either refused to fight against an enemy superior in numbers, or had been on furlough when the invasion began. Furthermore, he found out that the enemy had broken up their forces into small raiding parties which were plundering at will. When his army finally crossed the Channel with the onset of favorable spring weather, Theodosius had made his plans and was ready to move. The Roman army marched on Londinium (London) and re-established Imperial control of Britain's largest city. Using Londinium as his base of operations, Theodosius divided his army into detachments and sent them to attack bands of marauders within reach of the city. The Romans quickly killed or captured many of the small enemy raiding parties, relieving them of their booty, supplies and prisoners. Theodosius also sent messengers offering pardon to deserters and ordering them to make their way to Londinium. Over the winter of 368–369, large numbers of troops drifted back into their units, bringing vital intelligence that would help Theodosius plan the next phase of his campaign. In 369 Theodosius campaigned all through Roman Britain, restoring its 'chief towns' and hunting down enemy war parties and traitors. Ammianus Marcellinus records that he put down a rebellion by the Pannonian Valentinus. At the end of the campaigning season he sent a message to Valentinian to inform him that the provinces of Britain had been restored to the Empire. He also informed the emperor that he had created a new province which he had named Valentia (probably for Valentinian). Known to have been with him on this expedition were his son Theodosius, and the future emperor Magnus Maximus, possibly a relative. |

The Great ConspiracyIn 367, Valentinian received reports from Britain that a combined force of Picts, Attacotti and Scots had killed the Comes litoris Saxonici Nectaridus and Dux Britanniarum Fullofaudes. At the same time, Frankish and Saxon forces were raiding the coastal areas of northern Gaul. The empire was in the midst of the Great Conspiracy – and was in danger of losing control of Britain altogether. Valentinian set out for Britain, sending Comes domesticorum Severus ahead of him to investigate. Severus was not able to correct the situation and returned to Gaul, meeting Valentinian at Samarobriva. Valentinian then sent Jovinus to Britain and promoted Severus to magister peditum. It was at this time that Valentinian fell ill and a battle for succession broke out between Severus, a representative of the army, and Rusticus Julianus, magister memoriae and a representative of the Gallic nobility. Valentinian soon recovered however and in 367 appointed his son Gratian as his co-Augustus in the west. Ammianus remarks that such an action was unprecedented. Jovinus quickly returned saying that he needed more men to take care of the situation. In 368 Valentinian appointed Theodosius as the new Comes Britanniarum with instructions to return Britain to Roman rule. Meanwhile, Severus and Jovinus were to accompany the emperor on his campaign against the Alamanni. Theodosius arrived in 368 with the Batavi, Heruli, Jovii and Victores legions. Landing at Rutupiæ, he proceeded to Londinium restoring order to southern Britain. Later, he rallied the remaining garrison which was originally stationed in Britain; it was apparent the units had lost their cohesiveness when Fullofaudes and Nectaridus had been defeated. Theodosius sent for Civilis to be installed as the new vicarius of the diocese and Dulcitius as an additional general. In 369, Theodosius set about reconquering the areas north of London; putting down the revolt of Valentinus, the brother-in-law of a vicarius, Maximinus. Subsequently, Theodosius restored the rest of Britain to the empire and rebuilt many fortifications – renaming northern Britain 'Valentia'. After his return in 369, Valentinian promoted Theodosius to magister equitum in place of Jovinus.

|

First Gothic War: 367–369During Procopius's insurrection, the Gothic king Ermanaric, who ruled a powerful kingdom north of the Danube from the Euxine to the Baltic Sea,[46] had engaged to supply him with troops for the struggle against Valens. The Gothic army, reportedly numbering 30,000 men, arrived too late to help Procopius, but nevertheless invaded Thrace and began plundering the farms and vineyards of the province. Valens, marching north after defeating Procopius, surrounded them with a superior force and forced them to surrender. Ermanaric protested, and when Valens, encouraged by Valentinian, refused to make atonement to the Goths for his conduct, war was declared. In spring 367, Valens crossed the Danube and attacked the Visigoths under Athanaric, Ermanaric's tributary. The Goths fled into the Carpathian Mountains, and the campaign ended with no decisive conclusion. The following spring, a Danube flood prevented Valens from crossing; instead the Emperor occupied his troops with the construction of fortifications. In 369, Valens crossed again, from Noviodunum, and by devastating the country forced Athanaric into giving battle. Valens was victorious, and took the title Gothicus Maximus in time for the celebration of his quinquennalia. Athanaric and his forces were able to withdraw in good order and pleaded for peace. Fortunately for the Goths, Valens expected a new war with the Sasanid Empire in the Middle East and was therefore willing to come to terms. In early 370 Valens and Athanaric met in the middle of the Danube and agreed to a treaty that ended the war. The treaty seems to have largely cut off relations between Goths and Romans, confining trade and the exchange of troops for tribute.

|

||

|

On his return from Britain Theodosius succeeded Jovinus as the magister equitum praesentalis at the court of the Emperor Valentinian I, in which capacity he prosecuted another successful campaign (370/371) against the Alemanni. In 372 Theodosius was deployed to Illyricum and led an army against the Sarmatians; he appears to have secured a victory in battle and successfully brought the campaign to an end. In the same year, Firmus, a Mauretanian prince, rebelled against Roman rule and plunged the Diocese of Africa into disarray. Valentinian decided to give Theodosius the command of the expedition to suppress the rebellion. Theodosius' son was made dux of the province of Moesia Prima, replacing his father as commander in Illyricum, while Theodosius himself started mustering his troops at Arles. In the spring of 373 Theodosius sailed to Africa and led a successful campaign against the rebels in the east of Mauritania. At the end of the campaigning season, when he led his army into western Mauritania, he suffered a major setback. In 374 Theodosius invaded western Mauritania again. This time he was more successful, defeating the rebels and capturing Firmus. |

Revolt in Africa and crises on the Danube

In 372, the rebellion of Firmus broke out in the still-devastated African provinces. This rebellion was driven by the corruption of the comes Romanus. Romanus took sides in the murderous disputes among the legitimate and illegitimate children of Nubel, a Moorish prince and leading Roman client in Africa. Resentment of Romanus's personal use of public funds and his failure to defend the province from desert nomads caused some of the provincials to revolt. Valentinian sent in Theodosius to restore imperial control. Over the following two years Theodosius uncovered Romanus' crimes, arrested him and his supporters, and defeated Firmus. In 373, hostilities erupted with the Quadi, a group of Germanic-speaking people living on the upper Danube. Like the Alamanni, the Quadi were outraged that Valentinian was building fortifications in their territory. They complained and sent deputations to the magister armorum per Illyricum Aequitius, who promised to refer the matter to Valentinian. However, the increasingly influential minister Maximinus, now praetorian prefect of Gaul, blamed Aequitius to Valentinian for the trouble, and managed to have him promote his son Marcellianus to finish the project. The protests of Quadic leaders continued to delay the project, and to put an end to their clamor Marcellianus murdered the Quadic king Gabinius at a banquet ostensibly arranged for peaceful negotiations. This roused the Quadi to war, along with their allies the Sarmatians. During the fall, they crossed the Danube and began ravaging the province of Pannonia Valeria. The marauders could not penetrate the fortified cities, but they heavily damaged the unprotected countryside. Two legions were sent in but failed to coordinate and were routed by the Sarmatians. Meanwhile, another group of Sarmatians invaded Moesia, but were driven back by the son of Theodosius, Dux Moesiae and later emperor Theodosius. Valentinian did not receive news of these crises until late 374. The following spring he set out from Trier and arrived at Carnuntum, which was deserted. There he was met by Sarmatian envoys who begged forgiveness for their actions. Valentinian replied that he would investigate what had happened and act accordingly. Valentinian ignored Marcellianus’ treacherous actions and decided to punish the Quadi. He was accompanied by Sebastianus and Merobaudes, and spent the summer months preparing for the campaign. In the fall he crossed the Danube at Aquincum into Quadi territory. After pillaging Quadi lands without opposition, he retired to Savaria to winter quarters.

|

Persian War 373 |

||

|

|

Without waiting for the spring, Valentinian decided to continue campaigning and moved from Savaria to Brigetio. Once he arrived on 17 November, he received a deputation from the Quadi. In return for supplying fresh recruits to the Roman army, the Quadi were to be allowed to leave in peace. However, before the envoys left they were granted an audience with Valentinian. They insisted that the conflict was caused by the building of Roman forts in their lands; furthermore, individual bands of Quadi were not necessarily bound to the rule of the chiefs who had made treaties with the Romans – and thus might attack the Romans at any time. This attitude so enraged Valentinian that on 17 November 375, while angrily yelling at the envoys, he suffered a fatal stroke.

|

|||

|

In 375, when the Emperor Valentinian suddenly died, Theodosius was still in Africa. Orders arrived for Theodosius to be arrested; he was taken to Carthage, and put to death in early 376. The reasons for this are not clear, but it is thought to have resulted from a factional power struggle in Italy after the sudden death of Emperor Valentinian in November 375. Shortly before his death, which he accepted calmly, Theodosius accepted Christian baptism — a common practice at the time, even for lifelong Christians.

|

From above ... ... at this time that Valentinian fell ill and a battle for succession broke out between Severus, a representative of the army, and Rusticus Julianus, magister memoriae and a representative of the Gallic nobility. Valentinian soon recovered however and in 367 appointed his son Gratian as his co-Augustus in the west. Ammianus remarks that such an action was unprecedented.

|

Valens became the senior augustus when his older brother Valentinian died suddenly at Brigetio (Szőny) on 17 November 375 while on campaign against the Quadi in Pannonia. Though Valentinian’s elder son Gratian had been co-emperor since 367, the army on the Danube proclaimed Valentinian’s younger son Valentinian II augustus at Aquincum (Budapest), without consulting either emperor. | ||

Theodosius I / Theodosius the Great,

|

Gratian,

|

Valentinian II,

|

Valens,

|

|||

| Theodosius I (11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great was a Roman emperor from 379 to 395 |

Gratian (18 April 359 – 25 August 383) was emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 367 to 383. The eldest son of Valentinian I, Gratian was raised to the rank of Augustus as a child and inherited the West after his father's death in 375. Gratian was 16 years of age when his father died and he took over as Emperor of the West In summer 367, Valentinian became ill at Civitas Ambianensium (Amiens), raising questions about his succession. On recovery, he presented his then eight-year-old son to his troops on 24 August, as his co-augustus, passing over the customary initial step of caesar. |

Valentinian II (Latin: Valentinianus; 371 – 15 May 392) was a Roman emperor in the western part of the Roman empire between AD 375 and 392. He was at first junior co-ruler of his half-brother, then was sidelined by a usurper, and finally became sole ruler after 388, albeit with limited de facto powers. | ||||

| Theodosius received his first independent command by 374 when he was appointed the dux (commanding officer) of the province of Moesia Prima in the Danube. In the autumn of 374, he successfully repulsed an incursion of Sarmatians on his sector of the frontier and forced them into submission. Not long afterwards, however, under mysterious circumstances, Theodosius's father suddenly fell from imperial favor and was executed, and the future emperor felt compelled to retire to his estates in Hispania. |

The elder Valentinian died on campaign in Pannonia in 375. Neither Gratian (then in Trier) nor his uncle Valens (emperor for the East) were consulted by the army commanders on the scene. Instead of merely acknowledging Gratian as his father's successor, Valentinian I's leading generals and officials, including Merobaudes, Petronius Probus, and Cerealis, Valentinian II's maternal uncle and Justina's brother, acclaimed the four-year-old Valentinian augustus on 22 November 375 at Aquincum. The army, and its Frankish general Merobaudes, may have been uneasy about Gratian's lack of military ability, and to prevent a split of the army, so raised a boy who would not immediately aspire to military command. Also, he may have wanted to prevent more successful military commanders and officials, such as Sebastianus and Count Theodosius, from becoming emperors or gaining independent power, as Sebastianus was removed to a distant posting and Theodosius was executed within a year of Valentinian's elevation. Valentinian was only 4 years of age when his father died and he was proclaimed Emperor of the West |

|||||

|

Theodosius's period away from service in Hispania, during which he was said to have received threats from those responsible for his father's death, did not last long, however, as Maximinus, the probable culprit, was himself removed from power around April 376 and then executed. The emperor Gratian immediately began replacing Maximinus and his associates with relatives of Theodosius in key government positions, indicating the family's full rehabilitation, and by 377 Theodosius himself had regained his command against the Sarmatians |

When his father died on 17 November 375, Gratian inherited the administration of the western empire. Days later, Gratian's half-brother Valentinian was acclaimed augustus by troops in Pannonia. He was forced to accept the proclamation, though he did supervise his younger brother’s upbringing. Despite Valentinian being given nominal authority over the praetorian prefectures of Italy, Illyricum, and Africa, Gratian ruled the western Roman empire himself. His tutor Ausonius became his quaestor, and together with the magister militum, Merobaudes, the power behind the throne. Neither Gratian or Valentinian travelled much, which was thought to be due to not wanting the populace to realise how young they were. Gratian is said to have visited Rome in 376, possibly to celebrate his decennalia on 24 August, but whether the visit actually took place is disputed.

|

Gratian was forced to accommodate the generals who supported his half-brother into his realm, though he purportedly took a liking to educating his brother. According to Zosimus, Gratian governed the trans-alpine provinces (including Gaul, Hispania, and Britain), while Italy, part of Illyricum, and North Africa were under the rule of Valentinian. However, Gratian and his court was essentially in charge of the whole Western empire, including Illyricum, and Valentinian did not issue any laws and was marginalized in textual sources.

|

||||

|

Gratian's uncle Valens, returning from a campaign against the Sasanian Empire, had sent a request to Gratian for reinforcements against the Goths. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, Valens also requested that Sebastianus be sent to him for the war, though according to Zosimus Sebastianus went to Constantinople of his own accord as a result of intrigues by eunuchs at the western court. Once Gratian had put down the invasions in the west in early 378, he notified Valens that he was returning to Thrace to assist him in his struggle against the Goths. Late in July, Valens was informed that the Goths were advancing on Adrianople (Edirne) and Nice, and started to move his forces into the area. However, Gratian's arrival was delayed by an encounter with Alans at Castra Martis, in Dacia in the western Balkans. Advised of the wisdom of awaiting the western army, Valens decided to ignore this advice because he was sure of victory and unwilling to share the glory. The forces Gratian sent never reached Valens due to its commander feigning illness. Weeks later, Gratian had arrived in Castra Martis with a few thousand men, by which time Valens was at Adrianople (Latin: Hadrianopolis; Turkish: Edirne). Aware that Gratian's forces were not going to arrive, Valens attacked the Gothic army and as a result thousands of Romans died in the Battle of Adrianople along with Sebastianus and the emperor himself.

|

In 378, their [Gratian's and Valentinian's] uncle, the Emperor Valens, was killed in battle with the Goths at Adrianople, and Gratian invited the general Theodosius to be emperor in the East. As a child, Valentinian II was under the pro-Arian influence of his mother, empress Justina, and the courtiers at Milan, an influence contested by the Nicene bishop of Milan, Ambrose |

Second Gothic War: 376–378

Migrations of the Huns began to displace the Goths, who sought Roman protection. Valens allowed the Goths led by Fritigern to cross the Danube, but the Gothic settlers were abused by Roman officials and revolted in 377, seeking help from the Huns and the Alans and beginning the Gothic War (376–382). Valens returned from the east to campaign against the Goths. He asked for assistance from his nephew and co-emperor Gratian against the Goths in Thrace, and Gratian set out eastwards, though Valens did not wait for the western armies to arrive before taking the offensive. Valens' plans for an eastern campaign were never realized. A transfer of troops to the Western Empire in 374 had left gaps in Valens' mobile forces. In preparation for an eastern war, Valens initiated an ambitious recruitment program designed to fill those gaps. It was thus not entirely unwelcome news when Valens heard of Ermanaric's death and the disintegration of his kingdom before an invasion of hordes of barbaric Huns from the far east. After failing to hold the Dniester or the Prut rivers against the Huns, the Goths retreated southward in a massive emigration, seeking new settlements and shelter south of the Danube, i.e. Roman lands, which they may have thought could be held against the enemy. In 376, the Visigoths under their leader Fritigern advanced to the far shores of the lower Danube and sent an ambassador to Valens who had set up his capital in Antioch, and requested asylum. As Valens' advisers were quick to point out, these Goths could supply troops who would at once swell Valens' ranks and decrease his dependence on conscription from provinces—thereby increasing revenues from the recruitment tax. However, it would mean hiring them and paying in gold or silver for their services. Fritigern had enjoyed contact with Valens in the 370s when Valens supported him in a struggle against Athanaric stemming from Athanaric's persecution of Gothic Christians. Though a number of Gothic groups apparently requested entry, Valens granted admission only to Fritigern and his followers. Others would soon follow, however. When Fritigern and his Goths, to the number of 200,000 warriors and almost a million all told, crossed the Danube, Valens's mobile forces were tied down in the east, on the Persian frontier (Valens was attempting to withdraw from the harsh terms imposed by Shapur and was meeting some resistance on the latter's part). This meant that only limitanei units were present to oversee the Goths' settlement. The small number of imperial troops present prevented the Romans from stopping a Danube crossing by a group of Ostrogoths and yet later on by Huns and Alans. What started out as a controlled resettlement might any moment turn into a major invasion. But the situation was worsened by corruption in the Roman administration, as Valens' generals accepted bribes rather than depriving the Goths of their weapons as Valens had stipulated and then proceeded to enrage them by such exorbitant prices for food that they were soon driven to the last extremity. Meanwhile, the Romans failed to prevent the crossing of other barbarians who were not included in the treaty. In early 377, the Goths revolted after a commotion with the people of Marcianopolis, and defeated the corrupt Roman governor Lupicinus near the city at the Battle of Marcianople. After joining forces with the Ostrogoths under Alatheus and Saphrax who had crossed without Valens' consent, the combined barbarian group spread out to devastate the country before combining to meet Roman advance forces under Traianus and Richomeres. In a sanguinary battle at Ad Salices, the Goths were momentarily checked,[63] and Saturninus, now Valens' lieutenant in the province, undertook a strategy of hemming them in between the lower Danube and the Euxine, hoping to starve them into surrender. However, Fritigern forced him to retreat by inviting some of the Huns to cross the river in the rear of Saturninus's ranged defenses. The Romans then fell back, incapable of containing the irruption, though with an elite force of his best soldiers the general Sebastian was able to fall upon and destroy several of the smaller predatory bands. By 378, Valens himself was ready to march west from his eastern base in Antioch. He withdrew all but a skeletal force—some of them Goths—from the east and moved west, reaching Constantinople by 30 May, 378. Valens' councillors, comes Richomeres, and his generals Frigeridus and Victor cautioned Valens to wait for the arrival of Gratian with his troops from Roman Gaul, fresh from defeating the Alemanni, and Gratian himself strenuously urged this prudent course in his letters. But meanwhile the citizens of Constantinople were clamouring for the emperor to march against the enemy whom he had himself introduced into the Empire, and jeering the contrast between himself and his co-augustus. Valens decided to advance at once and win a victory on his own. According to the Latin historians Ammianus Marcellinus and Paulus Orosius, on 9 August 378, Valens and most of his army were killed fighting the Goths at the Battle of Adrianople, near Hadrianopolis in Thrace (Adrianople, Edirne). Read more about the Battle of Adrianople in Wikipedia. As part of the Gothic War of 376–382, the battle is often considered the start of the events which led to the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century.

|

||||

|

Theodosius's renewed term of office seems to have gone uneventfully, until news arrived that the eastern Roman emperor, Valens, had been killed at the Battle of Adrianople in August 378 against invading Goths. The disastrous defeat left much of Rome's military leadership dead, discredited, or barbarian in origin, to the result that Theodosius, notwithstanding his own modest record, became the establishment's choice to replace Valens and assume control of the crisis. With the begrudging consent of the western emperor Gratian, Theodosius was formally invested with the purple by a council of officials at Sirmium on 19 January 379.

|

In the immediate aftermath of Adrianople, Gratian issued an edict of tolerance at Sirmium, restoring bishops exiled by Valens and ensuring religious freedoms to all religions. Following the battle, the Goths raided from Thrace in 378 to Illyricum the following year. Convinced that one emperor alone was incapable of repelling the inundation of foes on several different fronts, Gratian, now senior augustus following Valens's death, appointed Theodosius I augustus on 19 January 379 to govern the east. On 3 August that year, Gratian issued an edict against heresy.

|

|||||

|

On 27 February 380, Gratian, Valentinian II, and Theodosius issued the Edict of Thessalonica. This edict made Nicene Christianity the only legal form of Christianity and outlawed all other forms of religion, bringing a period of widespread religious tolerance that had existed since the death of Julian to an end.

|

||||||

|

In September 380, the augusti Gratian and Theodosius met, returning the Roman diocese of Dacia to Gratian's control and that of Macedonia to Valentinian II. The same year, Gratian won a victory, possibly over the Alamanni, that was announced officially at Constantinople.

|

||||||

War against the Goths (379–382)The immediate problem facing Theodosius upon his accession was how to check the bands of Goths that were laying waste to the Balkans, with an army that had been severely depleted of manpower following the debacle at Adrianople. The western emperor Gratian, who seems to have provided only little immediate assistance, surrendered to Theodosius control of the prefecture of Illyricum for the duration of the conflict, giving his new colleague full charge the war effort. Theodosius implemented stern and desperate recruiting measures, resorting to the conscription of farmers and miners. Punishments were instituted for harboring deserters and furnishing unfit recruits, and even self-mutilation did not exempt men from service. Theodosius also admitted large numbers of non-Roman auxiliaries into the army, even Gothic deserters from beyond the Danube. Some of these foreign recruits were exchanged with more reliable Roman garrison troops stationed in Egypt. Throughout the second half of 379, Theodosius and his generals, based at Thessalonica, won some minor victories over individual bands of raiders, but suffered at least one serious defeat in 380, which was blamed on the treachery of the new barbarian recruits. During the autumn of 380, a life-threatening illness, from which Theodosius recovered, prompted him to request baptism. Some obscure victories were recorded in official sources around this time, however, and, in November 380, the military situation was found to be sufficiently stable for Theodosius to move his court to Constantinople. There, the emperor enjoyed a propaganda victory when, in January 381, he received the visit and submission of a minor Gothic leader, Athanaric. By this point, however, Theodosius seems to have no longer believed that the Goths could be completely ejected from Roman territory. After Athanaric died that very same month, the emperor gave him a funeral with full honors, impressing his entourage and signaling to the enemy that the Empire was disposed to negotiate terms. During the campaigning season of 381, reinforcements from Gratian drove the Goths out of Macedonia and Thessaly into Thrace, while, in the latter sector, Theodosius or one of his generals repulsed an incursion by a group of Sciri and Huns across the Danube. Following negotiations which likely lasted at least several months, the Romans and Goths finally concluded a settlement on 3 October 382. In return for military service to Rome, the Goths were allowed to settle some tracts of Roman land south of the Danube. The terms were unusually favorable to the Goths, reflecting the fact that they were entrenched in Roman territory and had not been driven out. Namely, instead of fully submitting to Roman authority, they were allowed to remain autonomous under their own leaders, and thus remaining a strong, unified body. The Goths now settled within the Empire would largely fight for the Romans as a national contingent, as opposed to being fully integrated into the Roman forces.

|

|

War against the Goths (379–382)

By 380, the Greuthungi tribe of Goths moved into Pannonia, only to be defeated by Gratian. Consequently, the Vandals and Alemanni were threatening to cross the Rhine, now that Gratian had departed from the region. With the collapse of the Danube frontier under the incursions of the Huns and Goths, Gratian moved his seat from Augusta Treverorum (Trier) to Mediolanum (Milan) in 381. He became increasingly aligned with the city's bishop, Ambrose, and the Roman Senate, shifting the balance of power within the factions of the western empire.

|

||||

| According to the Chronicon Paschale, Theodosius celebrated his quinquennalia on 19 January 383 at Constantinople; on this occasion he raised his eldest son Arcadius to co-emperor (augustus).[59] Sometime in 383, Gratian's wife Constantia died. Gratian remarried, wedding Laeta, whose father was a consularis of Roman Syria. Early 383 saw the acclamation of Magnus Maximus as emperor in Britain and the appointment of Themistius as praefectus urbi in Constantinople. On 25 August 383, according to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Gratian was killed at Lugdunum (Lyon) by Andragathius, the magister equitum of the rebel emperor during the rebellion of Magnus Maximus . Constantia's body arrived in Constantinople on 12 September that year and was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles on 1 December. Gratian was deified as Latin: Divus Gratianus, lit. 'the Divine Gratian'. |

In the summer of 383 Gratian was again at war with the Alamanni in Raetia. Gratian alienated the army by his favouritism towards his Alan deserters, whom he made his bodyguards and to whom he gave military commands. Other criticisms of his behavior were that he surrounded himself with bad company and neglected the affairs of state, preferring to have fun. Shortly after, the Roman general Magnus Maximus had raised the standard of revolt in Britain and invaded Gaul with a large army. Maximus, who had served under the comes Theodosius and had won a victory over the Picts in 382, was proclaimed augustus and crossed the channel, encamping near Paris. There, his forces encountered Gratian, but much of the latter's army defected to the usurper, forcing Gratian to flee. Gratian was pursued by Andragathius, Maximus' magister equitum and killed at Lugdunum (Lyon) on 25 August 383, supposedly against orders. Maximus then established his court at the former imperial residence in Trier. On the death of Gratian, the 12 year old Valentinian II became the sole legitimate augustus in the west.

Gratian was only 24 years of age when he was killed, which was not long after his second marriage

|

In 383, Magnus Maximus, commander of the armies in Britain, declared himself Emperor and established himself in Gaul and Hispania. Gratian was killed while fleeing him. As a lesser partner to Gratian in the West, Valentinian and his court in Milan had remained ineffectual and obscure until his brother's tragedy finally brought them to the forefront. For a time the court of Valentinian, through the mediation of Ambrose, came to an accommodation with the usurper, and Theodosius recognized Maximus as co-emperor of the West. | ||||

|

Theodosius, unable to do much about Maximus due to ongoing military inadequacy, opened negotiations with the Persian emperor Shapur III (r. 383–388) of the Sasanian Empire. According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Theodosius received in Constantinople an embassy from them in 384. In an attempt to curb Maximus's ambitions, Theodosius appointed Flavius Neoterius as praetorian prefect of Italy. In the summer of 384, Theodosius met his co-emperor Valentinian II in northern Italy. Theodosius brokered a peace agreement between Valentinian and Magnus Maximus which endured for several years. Theodosius I was based in Constantinople, and according to Peter Heather, wanted, "for his own dynastic reasons (for his two sons each eventually to inherit half of the empire), refused to appoint a recognized counterpart in the west. As a result he was faced with rumbling discontent there, as well as dangerous usurpers, who found plentiful support among the bureaucrats and military officers who felt they were not getting a fair share of the imperial cake. Theodosius's second son Honorius was born on 9 December 384 and titled nobilissimus puer (or nobilissimus iuvenis). The death of Aelia Flaccilla, Theodosius's first wife and the mother of Arcadius, Honorius, and Pulcheria, occurred by 386. She died at Scotumis in Thrace and was buried at Constantinople, her funeral oration delivered by Gregory of Nyssa. A statue of her was dedicated in the Byzantine Senate. In 384 or 385, Theodosius's niece Serena was married to the magister militum, Stilicho. In the beginning of 386, Theodosius's daughter Pulcheria also died. That summer, more Goths were defeated, and many were settled in Phrygia. According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, a Roman triumph over the Gothic Greuthungi was then celebrated at Constantinople. The same year, work began on the great triumphal column in the Forum of Theodosius in Constantinople, the Column of Theodosius. The Consularia Constantinopolitana records that on 19 January 387, Arcadius celebrated his quinquennalia in Constantinople. By the end of the month, there was an uprising or riot in Antioch (modern Antakya). The Roman–Persian Wars concluded with the signing of the Peace of Acilisene with Persia. By the terms of the agreement, the ancient Kingdom of Armenia was divided between the powers. By the end of the 380s, Theodosius and the court were in Milan and northern Italy had settled down to a period of prosperity. Peter Brown says gold was being made in Milan by those who owned land as well as by those who came with the court for government service. Great landowners took advantage of the court's need for food, "turning agrarian produce into gold", while repressing and misusing the poor who grew it and brought it in. According to Brown, modern scholars link the decline of the Roman empire to the avarice of the rich of this era. He quotes Paulinus of Milan as describing these men as creating a court where "everything was up for sale". In the late 380s, Ambrose, the bishop of Milan took the lead in opposing this, presenting the need for the rich to care for the poor as "a necessary consequence of the unity of all Christians". This led to a major development in the political culture of the day called the “advocacy revolution of the later Roman empire". This revolution had been fostered by the imperial government, and it encouraged appeals and denunciations of bad government from below. However, Brown adds that, "in the crucial area of taxation and the treatment of fiscal debtors, the late Roman state [of the 380s and 390s] remained impervious to Christianity".

|

||||||

|

The peace with Magnus Maximus was broken in 387, and Valentinian escaped to the east with Justina, reaching Thessalonica (Thessaloniki) in summer or autumn 387 and appealing to Theodosius for aid; Valentinian II's sister Galla was then married to the eastern emperor at Thessalonica in late autumn. Theodosius may still have been in Thessalonica when he celebrated his decennalia on 19 January 388.[59] Theodosius was consul for the second time in 388. Galla and Theodosius's first child, a son named Gratian, was born in 388 or 389. In summer 388, Theodosius recovered Italy from Magnus Maximus for Valentinian, and in June, the meeting of Christians deemed heretics was banned by Valentinian. The armies of Theodosius and Maximus fought at the Battle of Poetovio in 388, which saw Maximus defeated. On 28 August 388 Maximus was executed. Now the de facto ruler of the Western empire as well, Theodosius celebrated his victory in Rome on 13 June 389 and stayed in Milan until 391, installing his own loyalists in senior positions including the new magister militum of the West, the Frankish general Arbogast. According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Arbogast killed Flavius Victor (r. 384–388), Magnus Maximus's young son and co-emperor, in Gaul in August/September that year. Damnatio memoriae was pronounced against them, and inscriptions naming them were erased. |

In 386 to 387, Maximus crossed the Alps into the Po valley and threatened Milan. Valentinian II and Justina fled to Theodosius in Thessalonica. The latter came to an agreement, cemented by his marriage to Valentinian's sister Galla, to restore the young emperor in the West. In 388, Theodosius marched west and defeated Maximus. After the defeat of Maximus, Valentinian took no part in Theodosius's triumphal celebrations over Maximus. He and his court were installed at Vienne in Gaul. Justina had already died, and Vienne was far away from the influence of Ambrose [the Nicene bishop of Milan, Ambrose]. In a panegyric for Theodosius, the orator Pacatus asserted that the empire belonged to his two sons, Arcadius and Honorius, while barely mentioning the newly restored Valentinian. Theodosius remained in Milan until 391, appointing his supporters to important offices in the West. On the Eastern emperor’s coinage, Valentinian continued to be represented with the “unbroken” legend like Arcadius, depicting both of them as Theodosius’ junior colleagues. Modern scholars, observing Theodosius’ actions, suspect that he had no intention of allowing Valentinian to rule, due to his plan for his sons to succeed him. |

|||||

|

When Theodosius decided to return to the East, his trusted general, the Frank Arbogast, was appointed magister militum for the Western provinces (bar Africa) and guardian of Valentinian. Acting in the name of Valentinian, Arbogast was actually subordinate only to Theodosius. While the general campaigned successfully on the Rhine, the young emperor remained confined at Vienne, in contrast to his warrior father and his older brother, who had campaigned at his age. Arbogast's domination over the emperor was to the point where, in a report that Hebblewhite characterized as “admittedly outlandish,” the general is described as murdering Harmonius, a friend of Valentinian suspected of taking bribes, in the emperor's presence. Valentinian wrote to Theodosius and Ambrose complaining of his subordination to his general. In explicit rejection of his earlier Arianism, he invited Ambrose to come to Vienne to baptize him. The crisis reached a peak when Arbogast prohibited the emperor from leading the Gallic armies into Italy to oppose a barbarian threat. Valentinian, in response, formally dismissed Arbogast. The latter ignored the order, publicly tearing it up and arguing that Valentinian had not appointed him in the first place. The reality of where the power lay was openly displayed. |

||||||

|

In 391, Theodosius left his trusted general Arbogast, who had served in the Balkans after Adrianople, to be magister militum for the Western emperor Valentinian II, while Theodosius attempted to rule the entire empire from Constantinople. On 15 May 392, Valentinian II died at Vienna in Gaul (Vienne), either by suicide or as part of a plot by Arbogast. Valentinian had quarrelled publicly with Arbogast, and was found hanged in his room. Arbogast announced that this had been a suicide. Stephen Williams asserts that Valentinian's death left Arbogast in "an untenable position". He had to carry on governing without the ability to issue edicts and rescripts from a legitimate acclaimed emperor. Arbogast was unable to assume the role of emperor himself because of his non-Roman background. Instead, on 22 August 392, Arbogast had Valentinian's master of correspondence, Eugenius, proclaimed emperor in the West at Lugdunum.

|

On 15 May 392, Valentinian was found hanged in his residence in Vienne. Arbogast maintained that the emperor's death was suicide. Many sources believe, however, that the general had him murdered; ancient authorities were divided in their opinion. Some modern scholars lean toward suicide. McEvoy, Williams and Friell asserted that Arbogast had little reason to change his situation, while McLynn observed how no one benefitted from the emperor’s death. Ambrose's eulogy is the only contemporary Western source for Valentinian's death. It is ambiguous on the question of the emperor's death, which is not surprising, as Ambrose represents him as a model of Christian virtue. Suicide, not murder, would make the bishop dissemble on this key question. The young man's body was conveyed in ceremony to Milan for burial by Ambrose, mourned by his sisters Justa and Grata. He was laid in a porphyry sarcophagus next to his brother Gratian, most probably in the Chapel of Sant'Aquilino attached to San Lorenzo. He was deified with the consecratio: Divae Memoriae Valentinianus, lit. 'Valentinian of Divine Memory'.

Valentinian was only 21 years of age when he died. Valentinian was only 4 years of age when his father died and he was proclaimed Emperor of the West. Almost all his life he was Emperor, but perhaps in name only.

|

|||||

|

At least two embassies went to Theodosius to explain events, one of them Christian in make-up, but they received ambivalent replies, and were sent home without achieving their goals.[99] Theodosius raised his second son Honorius to emperor on 23 January 393, implying the illegality of Eugenius' rule. Williams and Friell say that by the spring of 393, the split was complete, and "in April Arbogast and Eugenius at last moved into Italy without resistance". Flavianus, the praetorian prefect of Italy whom Theodosius had appointed, defected to their side. Through early 394, both sides prepared for war. Theodosius gathered a large army, including the Goths whom he had settled in the eastern empire as foederati, and Caucasian and Saracen auxiliaries, and marched against Eugenius. The battle began on 5 September 394, with Theodosius' full frontal assault on Eugenius's forces. Thousands of Goths died, and in Theodosius's camp, the loss of the day decreased morale. It is said by Theodoret that Theodosius was visited by two "heavenly riders all in white" who gave him courage. The next day, the extremely bloody battle began again and Theodosius's forces were aided by a natural phenomenon known as the Bora, which can produce hurricane-strength winds. The Bora blew directly against the forces of Eugenius and disrupted the line. Eugenius's camp was stormed; Eugenius was captured and soon after executed. According to Socrates Scholasticus, Theodosius defeated Eugenius at the Battle of the Frigidus (the Vipava) on 6 September 394. On 8 September, Arbogast killed himself. According to Socrates, on 1 January 395, Honorius arrived in Mediolanum and a victory celebration was held there. Zosimus records that, at the end of April 394, Theodosius's wife Galla had died while he was away at war. |

At first Arbogast recognized Theodosius's son Arcadius as emperor in the West, seemingly surprised by his charge's death. After three months, during which he had no communication from Theodosius, Arbogast selected an imperial official, Eugenius, as emperor. Theodosius initially tolerated this regime but, in January 393, elevated the eight-year-old Honorius as augustus to succeed Valentinian II. Civil war ensued and, in 394, Theodosius defeated Eugenius and Arbogast at the Battle of the Frigidus.

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

The House of Theodosius |

The House of Theodosius |

The House of Theodosius |

||

Theodosius I / Theodosius the Great,

|

Arcadius,

|

Honorius,

|

||

|

Theodosius suffered from a disease involving severe edema. He died in Mediolanum (Milan) on 17 January 395, and his body lay in state in the palace there for forty days. His funeral was held in the cathedral on 25 February. Bishop Ambrose delivered a panegyric titled De obitu Theodosii in the presence of Stilicho and Honorius in which Ambrose praised the suppression of paganism by Theodosius. Theodosius was an impressive 48 years of age when he died. He ruled both East and West for just 135 days from the start date to the end date, end date included as a reunited Empire. Otherwise, 4 months 13 days. |

Arcadius (Greek: Ἀρκάδιος Arkadios; c. 377 – 1 May 408) was Roman emperor from 383 to his death in 408. He was the eldest son of the Augustus Theodosius I (r. 379–395) and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and the brother of Honorius (r. 393–423). Arcadius ruled the eastern half of the empire from 395, when their father died, while Honorius ruled the west. A weak ruler, his reign was dominated by a series of powerful ministers and by his wife, Aelia Eudoxia. | Honorius (9 September 384 – 15 August 423) was Roman emperor from 393 to 423. He was the younger son of emperor Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla. After the death of Theodosius in 395, Honorius, under the regency of Stilicho, ruled the western half of the empire while his brother Arcadius ruled the eastern half. His reign over the Western Roman Empire was notably precarious and chaotic. In 410, Rome was sacked for the first time in almost 800 years. | ||

|

Arcadius was born in 377 in Hispania, the eldest son of Theodosius I and Aelia Flaccilla, and brother of Honorius. On 16 January 383, his father declared the five-year-old Arcadius an Augustus and co-ruler for the eastern half of the Empire. Ten years later a corresponding declaration made Honorius Augustus of the western half. Arcadius passed his early years under the tutelage of the rhetorician Themistius and Arsenius Zonaras, a monk

|

After holding the consulate at the age of two in 386, Honorius was declared augustus by his father Theodosius I, and thus co-ruler, on 23 January 393, after the death of Valentinian II and the usurpation of Eugenius. When Theodosius died, in January 395, Honorius and Arcadius divided the Empire, so that Honorius became Western Roman emperor at the age of ten | |||

| Both of Theodosius' sons were young and inexperienced, susceptible to being dominated by ambitious subordinates. In 394 Arcadius briefly exercised independent power with the help of his advisors in Constantinople, when his father Theodosius went west to fight Arbogastes and Eugenius. Theodosius died on 17 January 395, and Arcadius, still aged only 17, fell under the influence of the praetorian prefect of the East, Rufinus. Honorius, aged 10, was consigned to the guardianship of the magister militum Stilicho. | ||||

The emperors from the founding of the Dominate in 284, in the West until 476 and in the East until 518, can be organised into one large dynasty plus various unrelated emperors. During most of this periods, though not always, there where two senior emperors ruling in separate courts. This division became permanent after the death of Theodosius I in 395.

The Dominate, also known as the late Roman Empire, is the despotic form of imperial government of the late Roman Empire. It followed the earlier period known as the Principate. Until the empire was reunited in 313, this phase is more often called the Tetrarchy.

It is in this period that I found the connections between Roman Emperors and my Family Tree.

The Family Tree continued to expand from this beginning.